Excerpt

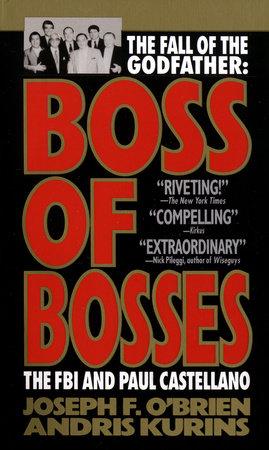

Boss of Bosses

Introduction

On December 16, 1985, at approximately five forty-five in the evening, Paul Castellano, the most powerful gangster in America -- the Mafia's Boss of Bosses -- was gunned down on a busy Manhattan street, along with his driver, bodyguard, and underboss, Thomas Bilotti.

The rubout was a classic instance of how the Mob deals with difficult questions of succession, and with qualms about internal security. Castellano had been at the top of the Mafia pyramid for nine years, since the 1976 death of his cousin and brother-in-law, Carlo Gambino. His reign had been a time of prosperity and relative stability for New York racketeers. But now Big Paul was seventy years old, and had diabetes, high blood pressure, and heart trouble. Unprecedented legal pressures were being brought to bear on him. He was a man beset, and he was tired; according to some, his grip on reality was loosening.

Some of his associates hated him, and he knew it. Being hated was not in itself a problem. It went with the job. Being hated without being feared, however, was dangerous, and Castellano was coming to realize that some of his young lieutenants -- most especially the cocky and ambitious John Gotti -- no longer feared him.

Or rather, they feared not his strength but his possible weakening. At the time of his death, Paul Castellano was on trial for running a stolen car ring and conspiring to commit murder. These charges, while serious enough, said less about the full gamut of Castellano's crimes than about the government's subtle and painstaking strategy of building cases against him piece by piece, one by one. He had already been indicted, arrested, and freed on bail in the famous Commission case, which would come to trial in 1986, and would essentially dismantle the Mob's entire leadership structure. The even more personally damning Castaway case, stemming from the bugging of Castellano's residence, was also being readied. The bottom line was that, win or lose, Big Paul would be in and out of court for years, and this made his underlings very nervous.

Unlike younger Mafiosi, whose mettle was proved and whose careers were sometimes made by an early show of loyalty and defiance that led to a conviction for contempt of court or obstruction of justice, Castellano had nothing to gain from a prison term. At seventy, the idea is not to impress but to survive. Castellano didn't want to be away from his doctors, from his supply of insulin and heart pills. He didn't want to be away from the gaudy comforts of his Staten Island mansion. He didn't want to be away from his mistress, who happened also to be his, and his wife's, Colombian maid.

For all those reasons, it was feared that Big Paul might sing. And to those who might be implicated in what Paul Castellano had to sing about, killing him seemed less trouble than enduring the worry and the sleepless nights that would attend his private confabulations with the authorities.

So the hit was arranged.

It was to be a highly public act -- no Hoffa-like disappearing routine -- and this, in the language of the Mob, sent a message: The murder was not a rebellion by some splinter faction of the Gambino clan, but a stratagem sanctioned by the five major Cosa Nostra families of New York. As in some primitive ritual, all members of the tribe would acknowledge, accept, and share responsibility for the slaying of the patriarch; they would all, so to speak, eat a piece of Paul.

Telling, too, was the fact that the killing took place uptown. Old-style Godfathers, when their time was up, tended to be eliminated in the linguine joints of Little Italy. They landed facedown in the clam sauce, their blood blended with the red-and-white-checked tablecloths, and the bullet holes in the walls behind them became tourist attractions. But Paul Castellano, who fancied himself a savvy and thoroughly American businessman, and who imagined that he was guiding the Mob into the promised land of legitimate enterprise, was murdered on the tony East Side -- to be exact, on Forty-sixth Street, between Second and Third avenues.

His last meal, had he lived to savor it, would have been eaten at Sparks Steak House, and would have consisted of the third cut of a prime rib of beef. Big Paul, a former butcher, claimed that this was absolutely the most succulent slice; it was his custom to examine the meat, raw, at his table before actually ordering. But regulars were expected to be demanding at Sparks. If the hundred-dollar Bordeaux was the slightest bit cloudy, back it went; sometimes even perfect wine was rejected, simply as a ceremony of power. Only three miles north from Angelo's of Mulberry Street, the uptown eatery was galaxies removed from the straw-covered Chianti bottles of Little Italy, from the communal wedges of pungent cheese, the thick espresso cut with anisette.

But despite the thin veneer of sophistication, the Mob was still the Mob, and the assassination of Castellano and Bilotti might as easily have happened in the Chicago of Al Capone.

Three men in trench coats, tipped off to Castellano's expected arrival by a confidant-turned-traitor named Frankie De Cicco, loitered in the urban shadows of the early Christmas-season dusk. Thomas Bilotti turned his boss's black Lincoln onto Forty-sixth Street, and parked it directly in front of a No Parking sign; the car had a Patrolmen's Benevolent Association sticker on the windshield. As the two victims emerged, the assassins approached them, producing semiautomatic weapons from under their coats and loosing a barrage of bullets at close range. Castellano and Bilotti were each shot six times in the head and torso. Nothing if not thorough, one of the killers then crouched over Castellano's body and delivered a coup de grace through the skull. In no particular hurry, the assassins jogged down Forty-sixth Street to Second Avenue, where a getaway car was waiting. Witnesses of the hits, of whom there were several, remembered no details except for the trench coats, and that the getaway car was a dark color.

Thomas Bilotti, a short, thickly muscled man who in life had been a hothead, a loudmouth, and a show-off, ended up sprawled in the middle of Forty-sixth Street, his arms and legs splayed wide apart in a final insistence on being noticed; around him spread a huge red stain, as though little Tommy's last gesture of machismo was to demonstrate how much blood his squat body had contained.

Paul Castellano, by contrast, had lived a life that was all discretion and self-effacement. He had worked hard at keeping his name out of the papers, and even in death he hid his face from public view. Shot, he fell backward toward the open door of his Lincoln, coming to rest with his head and neck grotesquely propped against the floorboard, his spine cantilevered over the curb, his long legs blocking the sidewalk like those of a sleeping wing. He hardly bled, as though age, sickness, and dread had already drained him dry.

If it is true that the manner of a person's death speaks the last word on his life, then the death of Paul Castellano, Boss of Bosses, made it clear that, for all the man's illusions of legitimacy and suavity, of business savvy and executive prowess, he had in fact remained a thug. Stripped of his power, bereft of his mystique, he ended up as one more gangland corpse, dead in public with his trousers unflatteringly hiked up to reveal a white sliver of calf above the translucent nylon sock.

If Paul Castellano's murderers had needed just)fication for killing him, they could have made a fairly persuasive case that their leader had doomed himself by a singular act of carelessness, lack of vigilance, or fatal overconfidence: he had somehow, in March 1983, allowed the FBI to bug his house.

Special Agents, with court approval, had foiled Castellano's complex alarm system and eluded the Doberman pinschers that patrolled his grounds. They had entered the Boss's private quarters -- the sanctum sanctorum of Mob business -- and planted a live microphone that functioned undetected, for almost four and one-half months. From the point of view of law enforcement, the Castellano bug was one of the most significant and fruitful surveillances in history.

From the Mafia's perspective, it was not only an unforgivable blunder on Castellano's part but a calamity of major proportions -- probably the greatest breach of Mob secrecy since a small-time hood named Joe Valachi decided to go public with his life story in the early 1960s. More than thirty Gambino crime family members were recorded discussing their illicit activities. Schemes were hatched, roles were assigned, while the Bureau listened in. Conversations with high-ranking members of other Cosa Nostra families provided fascinating insights into how the Mob's pie is divvied up. The machinery was laid bare.

So fertile were the Castellano tapes that even as the l990s were beginning, prosecutions stemming from the three thousand pages of transcripts were still under way. In all, more than a hundred indictments resulted from the bugging of Big Paul's Todt Hill residence. It is not an exaggeration to say that the destiny of the entire Gambino crime family was reshaped as a direct result of the surveillance.

Castellano's power and prestige were irreparably compromised by the bug. Not only did its successful placement cause him profound loss of face but the unflinching microphone caught him deriding associates, mocking fellow mobsters, setting factions against each other. As prescribed by law, everyone against whom the tapes were used as evidence had a right to review their contents; hearing themselves victimized by Big Paul's caustic wit, even formerly loyal cohorts turned on him. If ever a man was undone by thinking out loud, that man was Paul Castellano.

We -- the authors of this book -- are in a unique position to write about the Castellano surveillance, because we conducted it. We went in. We planted the mike. And we listened to the voices.

Special Agent Joseph F. O'Brien is one of two men who first penetrated the Staten Island mansion and made the bugging operation plausible, thus capping a four-year assignment to corner the Mafia chieftain. For this, in 1987, O'Brien was awarded the Attorney General's Distinguished Service Award, the nation's greatest honor for a law enforcement officer.

Special Agent Andris Kurins spent months monitoring the Castellano bug and supervised the painstaking process of transcribing the more than six hundred hours of recordings. In doing so, he became so conversant with the tapes' contents that he has been called to testify at eight different trials in which the material has figured as evidence.

It is our belief that there has never been a book like

Boss of Bosses -- a work that, from the inside and largely through actual dialogue, tells the true story of a Godfather. It is a story that exists on several levels. In part, it is a classic cops-and-robbers yarn, a tale of stakeouts, pay phones, code words, confrontations, and occasional danger. It is, in another sense, a sociological tract, a look at a curious organization which, in some surprising ways, resembles many other businesses -- except that this business's product line features extortion, theft, intimidation, and sometimes murder.

But beyond that, this is the very personal story of one man, Paul Castellano. In the course of our investigations, we got to know Big Paul intimately -- perhaps too intimately, because it seems to be part of our human makeup that intimacy carries with it sympathy, and we did not want to feel sympathy for our sworn enemy. Castellano was a hood -- but he was also a gentleman. He presided over an evil enterprise -- yet in his dealings with us he was always gracious, even courtly. Without question, Big Paul was responsible for many deaths, yet there is no evidence that he ever pulled a trigger, and some of his associates despised him for being too eager to make peace and too reluctant to take decisive, violent action. He was a bad man, but not the worst man.

Through the untiring microphone, we learned details of Castellano's private life that we almost wish we didn't know. His affair with his maid, under his own roof, was a squalid and blatant violation of the Mafia code of the sacredness of the home. Mafiosi had mistresses, of course, but they were not domestic servants, they were not Spanish-speaking, and they did not usurp the marital bed. Moreover, Castellano's age and infirmities were rendering him impotent, and as the tapes revealed, he would resort to extreme and bizarre medical procedures to try to recover some semblance, or some parody, of sexual manhood. At moments at least, it was difficult to chink of him as the mighty, all-powerful

capo; he seemed like an old, sick, and ordinary man, trying desperately to hold on to what remained of a flawed and faltering life.

There is an odd and sometimes uncomfortable bond between law enforcement officers and criminals. In a strange way, they need each other, as hunters and hunted need each ocher to establish their identities. Cops need criminals as a basis for their sense of mission. Criminals need cops to make them feel important and to assure them chat they are, in fact, flouting legitimate authority. But in the case of the FBI and the Mafia, there is a more specific bond as well. Both Bureau men and gangsters live by codes that are in certain ways more stringent than those of ordinary citizens. Codes of duty. Codes of loyalty. The fact that chose respective codes are in every way opposed does not change the fact that they share certain common emotional and psychological threads. A good FBI man understands the Mafia mind. And it is probably true chat a smart Mafioso understands the motivations and the pride of a Special Agent.

We feel we understood Paul Castellano, and it is our hope that this book reflects that understanding. While we bore Big Paul no personal animosity, we realized that we were locked with him in a deadly serious game where only one side could walk away the victor. We had confidence that, sooner or later, we would win. Did Castellano know that he was fated to lose? He never told us, as it would have been a violation of the stubborn dignity he retained to the end.

We are proud of the work we did in investigating the New York Cosa Nostra, and proud of the effect it had in exposing and disrupting the workings of organized crime in America. But it would be callous and dishonest not to acknowledge chat we also feel some dim element of regret that in the process a human being named Paul Castellano was humiliated, discredited in his own circle, and ultimately destroyed.

1

Back in 1981, a lot of people wanted to talk to Paul Castellano.

Every street-level wiseguy, from the garment district to the docks to the union halls to the espresso joints of Bensonhurst, would have jumped at the chance to sit down with the Boss and humbly inquire if he had any small favors he wanted done. Law enforcement officers from half a dozen different agencies would have found it very edifying to spend a quiet hour with Big Paul, learning what was on his mind. As for the media, they had long before established the convention of making celebrities out of Mafia bigs; they would have given a lot for an interview or some exclusive camera footage.

Strangely, though, for all the people who wanted to chat with Castellano, no one seemed to adopt the simple expedient of going to the front gate of his house and ringing the doorbell.

There were few things easier than finding Big Paul. Even in 1981, before his serious troubles had begun, he was mostly a stay-at-home, a recluse: the Howard Hughes of Mafiosi. Why go out? Why sit in traffic, why hang around on a torn vinyl chair in the back room of some crappy social club, when everything he needed was contained in his three-and-a-half-million-dollar mansion -- nicknamed the White House, which it somewhat resembled -- in Staten Island's pricey Todt Hill neighborhood?

At home, Castellano was literally on top of his world; his house occupied the highest point of land in the entire city of New York. He had a bocce court in his backyard. He had a swimming pool, Olympic size. He had ornately carved furniture upholstered in brocade, and huge lamps shaped like Renaissance sculptures and covered in gold leaf. He had a gorgeous view of the bold arc of the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge, looking across the water to profitable Brooklyn. He had a loyal and devoted wife, a frisky and diverting mistress, and an affectionate and charming daughter, all right there in the compound. It was pleasant, it was quiet, and it was safe. Why leave?

Still, though Castellano's whereabouts were hardly a mystery, most people seemed disinclined to drop in uninvited on the

capo di tutti capi.One of the few who weren't disinclined was Special Agent Joseph F. O'Brien of the New York office of the FBI, who, in late summer of 1981, had some rather pressing business to discuss. A contract, it seems, had been taken out on the life of one of his colleagues and the lives of the colleague's wife and children.

Such an action was out of bounds even in terms of La Cosa Nostra's own rules. At the famous Apalachin, New York conference of 1957, the Mob -- with Paul Castellano already a ranking member -- had decreed that certain activities were forbidden, not on humanitarian grounds but because they were lousy for public relations and would bring too much heat from law enforcement. Why get the cops mad if you could avoid it? Why make stars out of prosecutors? Why get the public clamoring for more funding and more manpower for the feds? Certain pastimes, while pleasurable or profitable or both, were just bad business. Taking revenge on FBI agents was one such activity. Dealing in narcotics was another.

But as in many sorts of American organizations, traditional Mafia standards had been eroding in recent years. Respect for the old rules was fading, internal discipline was getting ever harder to maintain, and no one knew this better than Paul Castellano. More and more of his time and energy seemed to go toward keeping his troops in line.

Rather like their counterparts on Wall Street, younger Mafiosi tended to put personal income ahead of the long-term good of the firm. It nettled them, for example, that they should be barred from dealing in heroin, cocaine, or crack while other, generally less well organized and usually despised ethnic groups made legendary sums from traffic in those substances. Since they didn't like the rule, the younger wiseguys ignored it. In this they were not so different from other generations of Mafia soldiers, who free-lanced in drugs, official prohibitions notwithstanding. But now a sinister new wrinkle had been added: the eighties dealers also tended to be users, especially of cocaine. They had the decidedly mixed blessing of easy access to huge amounts of stuff at wholesale prices. Drug use, in turn, further eroded discipline, self-restraint, and long-term thinking.

Given the increasing anarchy and hopheadedness, some of the younger guys simply could not see the logic of the ban on attacking the FBI. A guy is following you around, bothering you, interfering with your business and your digestion, hurting your profits, trying to put you in jail, and you're not allowed to shoot him or stick him in a bucket of cement? This, to some mobsters, seemed almost like a violation of their civil rights.

With each passing year, there were fewer old-style Dons around to explain, and enforce, the ancient wisdom. Some had died. Some were in prison. One -- Joe Bonanno -- had forfeited all authority by becoming an author. By the beginning of the 1980s, Paul Castellano had reason to feel he was the only one responsible for carrying on the old traditions. He was virtually the only one left with a long enough memory to recall the thinking behind the Apalachin edicts, and with enough muscle to see that, on his own turf at least, the edicts were obeyed. If a fed was attacked, the buck would not stop until it reached the Staten Island White House. Some trigger-happy punk with a noseful of blow might not take the time to consider this, but Castellano knew it painfully well. And the Bureau knew that Castellano knew it.

Not that the Mob didn't have reason to be upset with the agent whose life had been threatened. His name was Joseph D. Pistone, and he was without doubt the finest undercover man American law enforcement had ever produced. Pistone, under the alias of Donnie Brasco, had infiltrated the Bonnano crime family in 1976. Posing as a jewel thief, he had gotten close to one Lefty "Guns" Ruggiero, who'd vouched for him and gotten him accepted. Every day and night for six years, Pistone gave an Academy Award performance as an ambitious punk totally loyal to the organization. He only came out from "under" when his lieutenant ordered him to kill a rival family member. In the meantime, "Donnie" had gathered a vast amount of information that was later used in the Pizza Connection trial and the Commission case, and that helped put away more than one hundred Mafiosi. For his extraordinary efforts Pistone received the Distinguished Service Award in 1983.

Pistone beat the Mob fair and square, and under the old code of honor, that should have been the end of it. But it wasn't. Lefty Ruggiero, speaking brave words from his prison cell, had vowed to "get that motherfucker Donnie if it's the last thing I do." This, however, was not the main problem; Ruggiero would be away until 1992, and besides chances were good that as soon as he was released, he'd get whacked -- as punishment for his poor judgment in sponsoring Pistone in the first place. No, the real problem was that an open contract offering $500,000 for Pistone's life and/or the lives of his family had been put on the street. Any connected guy could cash in on it.

This could not be abided. The contract had to be canceled, and it could only be canceled from the top. It could only be canceled by the chieftain who was variously known as the Old Man, the Boss, and the Pope. It was time, therefore, to put good manners aside and drop in unannounced on Paul Castellano.

2

"Who ees eet?"

The coy, Spanish-accented female voice was not what Special Agents Joe O'Brien and Frank Spero had expected to hear from the other end of Big Paul Castellano's intercom. Playful and breezy, the voice threw them off stride for just a moment. They stood between two massive pillars on the portico of the Staten Island White House, shuffling their feet. Then Spero collected himself and put on an authoritative tone. "FBI," he said. "We have official business to discuss with Mr. Castellano."

"I see eef Meester Paul ees home," said the voice.

The intercom went silent, and for what seemed a long time, the two agents lingered on the porch, gazing off at the Verrazano Bridge and the waters of New York Bay, which, on that muggy August morning, glinted a greenish silver. Inside the house two large dogs were barking. Spero and O'Brien didn't speak, for fear chat an open intercom line would monitor their conversation; surveillance, after all, worked both ways. They were acutely aware of the two security cameras trained on them, panning slowly back and forth. All these things were parts of the Godfather's personal early-warning system, the machinery for guarding his cherished privacy.

Frank Spero, to pass the time and break the tension, put his hands in his pockets and started to whistle. He had been with the FBI since 1971, and like many law enforcement officers of Italian descent, he seemed to bring a special sense of mission to fighting organized crime. He had studied the Gambino crime family for years, becoming an expert on its complicated workings and far-flung personnel. Spero was also a particularly sturdy individual. He'd attended Wagner College, right there on Staten Island, on a football scholarship. He'd done three years in the Marines. He'd been a probation/parole officer -- a job known to entail a considerable, if unofficial, physical component. Now he was with the FBI, and, joined by the six-foot-five Joe O'Brien, established for the Bureau a commanding presence on Paul Castellano's porch.

Still, it was hard for both men not to feel intimidated standing there. The intimidation did not have to do with physical danger, which, at Castellano's home, in broad daylight, was virtually nil. Rather, it had to do with reminders of the sheer scale and wealth of the enterprise of which Big Paul was chief. The broad semicircular driveway, through which passed not only mobsters but a wide array of legitimate businessmen seeking favors or advice, bespoke the extent of Castellano's influence. The fluted white columns that dwarfed the agents provided a reminder of the old characterization of the Mafia as "a second government." The manicured grounds suggested order, confidence, even class. One might as well have been dropping in on the chairman of General Motors.

Except chat the chairman of GM, one expects, would probably not greet guests as Castellano did that morning: in a carmine-colored satin bathrobe over ice-blue silk pajamas, and in black velvet slippers, which on smaller feet might have looked effeminate, but on Castellano's seemed imperial. Nor would most legitimate executives choose to conduct their business on the porch. But Castellano, unaccompanied and confident, emerged abruptly from his house, quickly closing the enormous oak front door behind him, as if he didn't want the feds to have even a glimpse of the interior of his residence. Perhaps he had a premonition that FBI men in his house would be the start of his undoing.

"Okay," he began, as abruptly as he'd appeared, "what can I do for you gentlemen?" His tone was neither friendly nor surly, simply businesslike.

As previously agreed, Spero did most of the talking, apprising Castellano of the contract on Joe Pistone, and leaving O'Brien free to study the Pope himself.

Castellano was a big and bulky man, six feet two, not handsome but imposing. Although he was then sixty-six years old, his hair was still thick and mostly dark, shot through here and there with silver threads, carefully combed back and slicked down. His posture was ramrod straight as far as his shoulders, but his massive head hung sligtly forward on his heavy neck, creating a somewhat buzzardlike effect. He had a strong Picasso nose that branched off directly from his forehead, and black eyes chat seemed vigilant yet tired, with liverish sacs under them. His mouth was broad but thin-lipped, and his expressions -- as the agents were to learn -- always seemed ambiguous, as though from a lifetime's practice at not revealing too much. When Castellano smiled, the grudging upturn of his lips also suggested something of a grimace, something mocking; on the ocher hand, when he looked most serious, most grim, the impact was leavened by a certain facetious curl that hinted at bleak amusement. His hands were huge, and although the nails were immaculately manicured, the thick wrists and gnarled fingers betrayed a past of manual labor. In Castellano's former trade of butchery, he'd hoisted a lot of carcasses, plucked out many rough ribbons of sinew, hacked through thousands of ribs.

"And we want to advise you," Frank Spero was summing up to Castellano, keeping the language formal and temperate, "that if any harm comes to Agent Pistone or any member of his family, the full resources of the FBI and the Department of Justice will be brought to bear against you and your associates. Is that clear, Mr. Castellano?"

The Boss stood with his arms crossed, looking out calmly toward the bridge. He didn't seem surprised by the agents' errand, he didn't seem ruffled, and he didn't seem angry. "I understand your concern," he said.

To chose whose impression of the way Mafia Dons talk has been forever shaped by the gravelly, mouth-full-of-marbles performance of Marlon Brando in the

Godfather films, Castellano's voice would have sounded strangely familiar. Not that Big Paul was quite so thick-tongued and portentous. No -- in volume and cadence, his speaking voice was standard Brooklyn-American; it could have belonged to a cabdriver, a grocer, or, for that matter, a cop. Yet there was a certain labored breathiness in his tone, a suggestion of forcing the air through a clenched throat and not parting his teeth if he could help it. "I understand," he repeated, "your concern about your friend."

"We'd like more than understanding," Spero pressed. "We'd like some assurances."

This request put Castellano in a difficult position. He didn't want to acknowledge that the contract in fact existed, or that he had known of it before; he certainly would not admit that he had the power to have it squelched. So he just put his enormous hands into the pockets of his red satin robe, and issued forth a smile that would have seemed positively benevolent had not one corner of his mouth pointed stubbornly down. "Gentlemen," he said, "if you know anything at all about me, you know that I would never go along with anything like that."

There was a pause, during which Spero and O'Brien each concluded that they had probably gotten the Boss to go as far as he was going to. They'd contacted him. They'd made their pitch. He'd listened. To expect more than that would have been unrealistic. Mobsters, after all, had a well-earned reputation for speaking in half-thoughts, half-sentences, half-promises. It was a point of pride with them to say as little as possible. It was almost a game: he who made things more explicit was the loser. The Bureau men should be happy with what they'd gotten.

But then, rather to the agents' surprise, Castellano spoke again, picking up exactly where he had left off. "I have too much respect for the FBI for that," he said.

Was he being sincere, or sarcastic? Was he making nice, or goading? From his neutral tone of voice and crooked half-smile, it was impossible to tell.

"Nice of you to say," said O'Brien. It was the first time he had spoken, and he was trying to answer Castellano's ambiguity in kind. It wasn't something he was used to, and he secretly felt he didn't do it very well. The mixed message, like any other art form, took practice to perfect.

"Just do me one favor," Castellano said.

"What would that be, sir?" asked Frank Spero.

"Don't frame me. You have a case to make sometime, make it. But don't play games. Don't make something out of nothing. I've seen that happen, and it stinks."

O'Brien considered protesting this remark, then let the moment pass. It wasn't the time to discuss the question of justice with Paul Castellano. On very rare occasions, it was true, a mobster got nailed big for something small. This compensated in some tiny way for the many times said mobster got away scot-free for crimes that were large -- murder, for example. No one ever said the system was perfect, only that over the long haul, it usually balanced out.

"We won't frame you, Mr. Castellano," said Joe O'Brien. And this time, without any conscious effort on his part, he managed to imbue the words with a full freight of ambiguity, hitting a note of patient menace even while keeping a pleasant smile on his face.