Excerpt

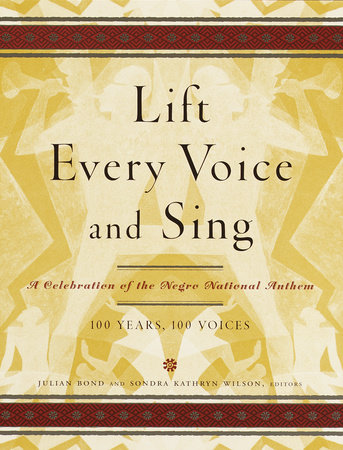

Lift Every Voice and Sing

It is wondrous and hardly explicable to many how James Weldon Johnson could have written such spiritually enriching lyrics in 1900 despite the restraints ordained by Jim Crow laws, despite frenzied lynchings and mob violence, despite the fact that white America had established an educational system teeming with stereotypes that had misrepresented and malformed virtually every external view of African American life. Underpinning these sweeping injustices was the Supreme Court's ruling in the infamous Plessy v. Ferguson case four years before "Lift Every Voice and Sing" was written in 1900. This decision meant that state laws requiring "separate but equal" facilities for African Americans were a "reasonable" use of state powers. Further, "The object of the [Fourteenth] Amendment was undoubtedly to enforce the absolute equality of the two races before the laws, but in the nature of things it could not have been intended to abolish distinctions based on color, or to enforce social, as distinguished from political, equality, or a commingling of the two races upon terms unsatisfactory to either."

"Lift Every Voice and Sing" is fittingly provocative. Yet its message, ingeniously crafted, does not fuel the fires of racial hatred. Sociologist E. Franklin Frazier pointed out that in "Lift Every Voice and Sing," James Weldon Johnson endowed the African American enslavement and struggle for freedom with a certain nobility. Frazier further noted that Johnson expressed an acceptance of the past and confidence in the future. It is likely that Johnson was attempting to cultivate a sense of history among his race. On the one hand, the lyrics reveal how African Americans were estranged from their cultural past by the impact of racial oppression and that they manifested the psychological and physical scars inflicted by that injustice. On the other hand, the song is irrefutably one of the most stalwart and inspiring symbols in American civil rights history. Not wanting African Americans to lose hope, James Weldon Johnson included in the lyrics none of his pragmatic reservations regarding justice for his race. His enriching directive is assuredly one of the mainstays of the song's mastery and endurance. Notwithstanding, he tells us in "Lift Every Voice and Sing" that we must persist—we must remain vigilant until victory is won.

To understand how James Weldon Johnson conceived and produced such motivating lyrics when white supremacy served as the backdrop of virtually every phase of black life, one has to comprehend his beliefs and experiences, so clearly evident in the "everlasting" song he called "the Negro National Hymn." In the lyrics we see his unswerving self-confidence and optimism, his faith in African Americans, and his strong belief that the then existing system, a counterfeit representation of the United States Constitution, could not endure.

Johnson's self-confidence and optimism are easily discernible in his early life. As a boy he staunchly proclaimed that he wanted one day to be the governor of his home state of Florida. His parents, James and Helen Dillet Johnson, had instilled in him and in his younger brother, J. Rosamond Johnson, such a sanguine view of America that the boys surely believed that whatever their young minds could conceive, they could achieve. During his early years, James believed himself beneficiary to all the privileges afforded any American who desired to develop his full potential. But while attending Atlanta University, he came to understand that the Jim Crow system did not allow status or individual liberation for African Americans, no matter what they achieved. This harsh realization enabled him to see through the deception of white supremacy. He was determined to acknowledge the effects of racism, but he was even more resolved not to internalize them. Therefore, his innate optimism remained firmly intact. "Lift Every Voice and Sing" illustrates James Weldon Johnson's understanding of the existing system as well as his confidence in the future. His determination to remain spiritually unfettered by the effects of racism is evident in the following pledge he wrote.

I will not allow one prejudiced person or one million or one hundred million to blight my life. I will not let prejudice or any of its attendant humiliations and injustices bear me down to spiritual defeat. My inner life is mine, and I shall defend and maintain its integrity against all the powers of hell.

His confidence in his race is unmistakably personified in "Lift Every Voice and Sing." This faith in the family of race was reinforced during his college years and while teaching in the backwoods of Georgia. As a student at Atlanta University during the late nineteenth century, James Weldon Johnson recognized that the subject of race was almost invariably the topic of debates, speeches, and essays. He acknowledged, "The atmosphere was charged with it. Nearly all that was acquired, mental and moral, was destined to be fitted into a particular system, of which race was the center."

His teaching experience in rural Henry County, Georgia, the summer following his freshman year of college, proved to be a momentous spiritual and educational manifestation. It was here, where the adversarial relations between black and white were flagrant and inescapable, that he was introduced to the crude dimensions of racism. Through this experience, he accepted that his people had been obstructed for centuries by prejudice, intolerance, and brutality, and hobbled by their own ignorance, poverty, and helplessness. Nonetheless, he believed, in the face of this weighty burden they remained courageous and unvanquished. This hopefulness, he wrote, was evidenced in their capacity to fervently sing of a better day. Writing about his newfound faith and pride in his people, he contended, "I laid the first stones in the foundation of faith in them on which I have stood ever since."

Resolving that the race problem was paradoxical, he wrote that white America's superior status was not always real, but often imaginary and artificially bolstered by bigotry and buttressed by the forces of injustice.Ý Asserting that this false position could not infinitely defy the truth, he reasoned that white America's belief in its mental, moral, and physical superiority was specious. Knowing that the American system of democracy was deceptive, and believing that many white Americans realized this fact also, he was moved to proclaim, "Undoubtedly, some people will find it difficult to understand why a supremacy of which we have heard so much, a supremacy which claims to be based upon congenital superiority, should require such drastic methods of protection."

As a college student, Johnson had realized the glaring contradictions between white America's actions and the true aims of the United States Constitution. He believed that the Constitution meant exactly what it said, and it was his inexorable faith in the founding principles of America that inspired him to write "Lift Every Voice and Sing" not as an anthem but as a hymn. He did not conceive the song as an anthem, and at no time did he refer to it in that manner. By the 1920s the song was being pasted inside the back covers of hymnal books across the South and in many parts of the North. It is likely that around this time the "anthem" label evolved through folklore, thus sealing the song's permanent status among African Americans as their "Negro National Anthem."

James Weldon Johnson was the chief executive officer of the NAACP during the 1920s, when the organization made "Lift Every Voice and Sing" its "official song." Because of his strong belief that "a nation can have but one anthem" and the NAACP's fundamental ideology of integration, labeling the song an "anthem" would have been antithetical to the organization's central objective. Johnson's main task as NAACP leader was to legally abolish the fiendish acts of lynchings that were increasingly occurring; he called for the saving of black America's bodies and white America's souls. He certainly understood that when the wide-ranging forces of racism struck, his people needed something to fall back on. And it was clear to him that African Americans made the song what they needed it to be—their anthem of hope and prayer.