Excerpt

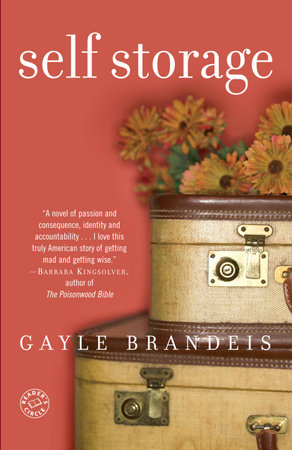

Self Storage

Part One

"Unscrew the locks from the doors!

Unscrew the doors themselves from their jambs!

I celebrate myself Sorry. I just can’t do it.

Walt Whitman starts “Song of Myself,” the greatest poem in the world, with those three words. I wish I could follow his lead, start the same way, but I can’t. The words sound tinny in my own voice—arrogant, wrong. Maybe someday I’ll be able to say “I celebrate myself” freely, even joyfully, like he does, but I’m not there yet.

Whitman’s book saved my life. Leaves of Grass saved my ass. If it wasn’t for that book, I might be in jail right now. If it wasn’t for that book, I wouldn’t be writing this one.

I have to admit, it’s a bit intimidating to write under Whitman’s long and illustrious shadow. I suppose I could try to picture him in his underwear. It worked for Marcia Brady when she gave her big speech (not that Whitman was in the audience at Westdale High). I have an advantage: I’ve already seen Whitman naked. A series of photos by Thomas Eakins from the early 1880s—“Old man, seven photographs.” Whitman’s name isn’t mentioned, but I can tell it’s him. Others have thought so, too. He was pretty cute for a sixty-something-year-old. I love how his belly pouches out just a little, the way my daughter Nori’s does over her diaper. I love the way he cocks one hip to the side—a little peevish, a little saucy. I love seeing him stripped bare.

I guess I have to strip myself bare here. I have to unload all that happened these last few months. If I write it down, there’s a chance I’ll begin to understand it.

One image keeps coming back to me. An image of Sodaba, my neighbor from Afghanistan, hunched inside the storage locker. The front of her burqa was flipped up off her face; it hung down the back of her head like a nun’s habit. She was turned slightly away from me; tendrils of hair were plastered against the side of her neck. The wide plane of her left cheek was slick with sweat. That was the first time, the only time, I saw any part of her face. I never learned the true shape of her lips or nose, the full scope of her eyes—just that wet expanse of skin before she realized I was there and pulled the veil back down. The skin of her cheek looked so smooth. It gives me chills to think about it now.

But that’s not where I want to start.

I want to go back to my normal life, before her life collided with mine. Back when I had more simple things to worry about—my kids’ lunches, my husband’s TV addiction, the auctions I attended each week.

The auctions. Of course. I could celebrate my self-storage auctions. That is something I think I could do.

This is how the auctions work.

You get one minute with a flashlight.

The auctioneer breaks open the padlock with a blowtorch or bolt cutters, and you get one minute to stand in the doorway of the storage locker. One minute to peer inside and decide whether the wrinkled black trash bags, the taped cardboard boxes, the bicycle parts and beach chairs and afghans that reveal themselves in your mote-filled path of light, are worth your while.

You learn to trust your intuition. You learn to listen to that ping inside your gut that tells you to bid. You learn to look for the subtle clues—the shopping bags with a Beverly Hills address, the boxes marked fragile with a sharp black marker. You learn to avoid certain smells—mold and mildew are no good; you’ll probably end up with a bunch of old sweatshirts and socks that someone put in the wash but never bothered to dry properly, just left them to rot in plastic sacks. You develop a sixth sense for the smell of jewelry, the smell of electronics. TVs emit a hot, charged smell, even if they haven’t been turned on for years, while diamonds smell blue, like sweet cold water.

You try to remember that you’re bidding on someone else’s misfortune. Someone who couldn’t pay for their storage locker, who let it lapse into lien. You try to remember that you are benefiting from someone’s sadness, someone’s failure, that the money you’ll gain from this merchandise will come from someone else’s loss. You try to remember that there was a self who first put these items in storage, a self who one day planned to take them all back, a self who will miss these photo albums and brittle swim fins and frames filled with dried beans. But you push this all aside when the auctioneer says “Bidding will start at one dollar,” and your own self muscles its way to the front, and your own hand flies into the air.

I lifted my chin. Just the slightest tick. A few centimeters at the most. A small tilt of the head, a concurrent yet subtle lift of the brow. I wanted to see how small I could make my movement and still be noticed by the auctioneer. The auctioneer standing on a step stool in his Hawaiian print golf shirt and cargo shorts, the auctioneer with his Ray-Bans and poofy hair, saying “TendoIheartententengoingoncegoingtwice . . . ,” his mouth looking too solid to go so fast. Then he said “Sold to Flan Parker for ten dollars,” and I felt like I had been granted superpowers.

Early in my auction career, I waved both arms to bid. Soon I shifted to one flailing arm. Then one calm arm. Then a single hand. Then a finger. Then the chin. I thought maybe I would get to the point where the auctioneer would notice my pupils dilating, and that would be that.

I fanned myself with the auction list and gave my two-year-old daughter a sip of water. I wished I had been granted superpowers to keep us cool. The year 2002 was one of the hottest on record so far. Even the palm trees seemed to be drooping in the hundred-degree early-June weather. Everything at EZ Self Storage seemed to be drooping, not necessarily because of the intense Riverside heat. It was an older self-storage complex, and the owners hadn’t done much to spruce it up over the years. Like most self-storage establishments, it consisted of row upon row of low, rectangular buildings fronted with a series of garage doors. The walls were all unpainted cinder block, gray and crumbly-looking; the roll-up doors had probably been bright yellow at some point, but now were dinged and hammered into a dull, bruised shade. The asphalt on the ground was cracked and pitted, shot through with weeds. I wondered who would want to store their stuff in such a decrepit place.

I looked into the unit I had won. I couldn’t wait to find out what was inside one particular JCPenney’s bag. The plastic sack looked blocky, like it was full of transistor radios. Possibly bricks of gold.

Stuff’d with the stuff that is coarse and stuff’d with the stuff that is fine. “Good work,” said Mr. Chen-the-elder, a dapper junk-shop owner and fellow bidder. He patted me on the shoulder and ruffled Nori’s white-blond hair. The auctioneer folded up his step stool and put his clipboard under one arm, his red three-foot-long bolt cutters under the other. The crowd of eight or so of us rambled after him to the next garage door, the last unit of the day, a ten-by-fifteen, most likely out of my league. I just went for the “Flan lots,” as my auction cronies had dubbed them. No big-ticket items, just modest assortments of boxes and bags, things I could easily carry to the car myself while pushing Nori’s stroller. I was usually able to get them for the opening bid. Most of the bidders weren’t interested in the small stuff—they wanted the furniture, the appliances, the big-money pieces; most of them were dealers with pawnshops or stalls in antiques stores. My yard sales were small potatoes. The lots full of antiques could start at over $100 and could go to several hundred, cash only, but they were still a steal. People generally earned back at least twice what they paid in auction once they sold the goods; sometimes they earned back ten times the amount. Sometimes more.

The lot on the block was full of instruments—a drum kit with amendz written on the front of the bass drum in electrical tape, a couple of guitars plastered with stickers, a stand-up bass, a saxophone, all set up like the band had just left to get their requisite groupie blow jobs. A few beer bottles and a couple of towels were scattered over the concrete floor. The storage unit had obviously been a rehearsal space. How could a band let all their instruments go into lien? Maybe everyone died in a Central American bus crash; maybe their wives had nagged them into giving up their rock ’n’ roll dreams.

Nori struggled to get out of her stroller. I had augmented the buckle with a complicated knotting of twine to thwart her escape attempts. Nori had become quite the little Houdini lately; it was getting harder to restrain her.

“Tigars, Mama!” She pointed to the guitars. I tried to hush her; the auction was about to start. I wasn’t very successful—she screamed at the injustice of being trapped in her small canvas seat. The auctioneer raised his speeding voice.

Mr. Chen-the-younger, a slightly shabbier version of his father, lifted a finger when the bidding reached $250. Yolanda Garcia gave her bouffant-fluffed head a quick tilt to the right when it got to $375. Soon after, Norman, the crusty old swap-meet man, shouted “Right here” over Nori’s cries of protest, lifting both of his veiny hands.

“Sold to Norman for $425,” the auctioneer bellowed. “Good going, everyone.” He shot Nori a slightly reproachful glance. “I’ll meet y’all in the office for payment.”

It was an easy transaction for me—ten bucks for at least a dozen bags and boxes. I couldn’t wait to bring them home and crack them open.