Excerpt

Manga: The Complete Guide

INTRODUCTION

In the early twenty-first century, a sight began to appear in American bookstores that was familiar to anyone from Japan: crowds of people reading books in the manga section. In Japan they call it tachiyomi, “stand-reading,” and it is strongly discouraged, but in America it seems slightly more acceptable, perhaps because bookstore staff are too overworked, or perhaps because no other phenomenon has brought so many young adults and teenagers into the stores. Ten years ago most American bookstores had no manga section, and ten years before that most video stores had no anime section. Manga, comics made in Japan for Japanese audiences, have been embraced in America. We love them more than any test-marketed, focus-group products designed for us. If we can accept stories told with pictures, we can read manga. If we read comic books, newspaper strips, or online comics, we can read manga. If we can look the characters in their (sometimes) big eyes and take their stories at face value, we can read manga. And more and more of us do.

What are manga like? The question is like asking “What are books like?” or “What are DVDs like?” Manga aren’t a single genre, like superhero comics or fantasy novels. They don’t have a single style, with big eyes or speedlines or samurai swords. The term “manga” covers all Japanese comics, including stories for men and women, children and adults. Historical drama, comedy, romance, horror, science fiction, sports, experimental works—manga span every genre imaginable. You may think you know “the manga style,” but there are manga that look nothing like it.

Manga have been in America for more than twenty years; the first full-length manga were translated in 1987, and one of those books, Lone Wolf and Cub, is still in print. Latin America, Europe, and most of Asia have been reading translated manga for decades. The United States is one of the last places for the phenomenon to hit, but hit it has. As of 2007, more than one thousand manga series have been translated; not individual books, but epic stories often running twenty volumes or more. (If it sounds intimidating, there are many one-volume manga as well.) More than one hundred volumes of manga are now released in America every month, not counting similar-looking books published in the same format, such as manga-influenced American comics and Korean manhwa. Manga has surpassed anime as the up-and-coming export of Japanese pop culture (video games are the only possible competition). Anime conventions have taken place in America for years, but in October 2006 the first manga convention, Manga Next, was held in New Jersey.

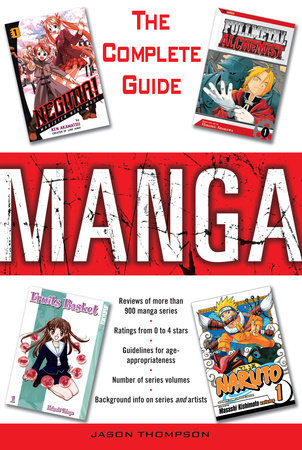

Manga: The Complete Guide lists every manga that has ever been translated for American audiences, as well as a few that were made for Americans by Japanese artists. Here you’ll find the new bestselling series with the covers bent back from tachiyomi, but you’ll also find rare manga that were translated in the 1980s and 1990s, e-books, and even bilingual books printed in Japan. From the mainstream to the underground, from family-friendly to adult, this book has everything. Are you looking for a particular manga? Look it up in the title or artist index. Or maybe you don’t have a manga in mind, but you’re a fan of a particular genre, such as mystery, fantasy, or sports. In the table of contents are listed more than thirty articles on different topics. The amount of translated material is still a fraction of what is produced in Japan, but today there are translated examples of almost every manga genre, including rarely seen ones such as pachinko comics, military comics, and comics for businessmen.

Manga is popular around the world and has inspired comic artists everywhere. But no one is influenced by manga in general; people are influenced by specific artists, specific works. If you’re already familiar with manga, you may know what you want to look up. But I think I envy the newbies more this time. More than one thousand manga await you. Jump in.

Check out http://www.delreymanga.com/mangaguide for periodic online updates to Manga: The Complete Guide and to give us your feedback. The Web site includes manga that were announced too late to make it into the book.

SIXTY YEARS OF JAPANESE COMICS

Manga ( or ) is Japanese for “comics.” Coined in the 1800s by the Japanese artist Hokusai to refer to doodles in his sketchbook, the term can be translated as “whimsical sketches” or “lighthearted pictures.” The same term is the root of the Korean word for comics (manhwa) and the Chinese word (manhua). Today, most Japanese people use the English word “comics” (komikku) as well.

Almost as soon as modern printing technology was introduced to Japan in the late 1800s, comics were published: first European-style satirical cartoons, then American-style newspaper strips, and eventually monthly comics magazines aimed at young readers. The oldest manga available in translation, The Four Immigrants Manga, was drawn by Henry (Yoshitaka) Kiyama while he was living in San Francisco in 1931. After World War II, the Japanese manga industry was quick to rise out of the ashes. TV was not common in Japan until the late 1950s, and movies were always expensive, so comics were cheap, accessible entertainment. Some artists developed self-contained comic stories for kashibonya—professional book lenders or “pay libraries”—who loaned hardbound comic books for a small fee. Others drew manga for a new crop of children’s magazines, now printed in black and white instead of color because of postwar economic realities. The most popular magazine series were collected and repackaged as graphic novels (or, in Japanese, tankôbon). In this environment of frantic experimentation, today’s “classic” manga artists established the styles that future generations would mimic.

As the Japanese economy improved, manga adapted. Kashibonya became a thing of the past, but monthly and biweekly manga magazines could be purchased at any newsstand. To compete with the fast pace of TV, the biggest publishers introduced weekly magazines, starting with Weekly Shônen Magazine in 1959. Manga were licensed for anime, toys, and live-action movies. At the same time, the form began to achieve critical respect; Sanpei Shirato’s epic Ninja Bugeichô (“Ninja Military Chronicles,” 1959–1962) was a favorite with student radicals due to its revolutionary themes. Art and stories became more diverse: sports, horror, war stories, science fiction, occupational manga, manga for adult readers. Sales rose throughout the 1970s and 1980s until the bestselling boys’ magazine Weekly Shônen Jump sold more than five million copies a week. As manga became a bigger and bigger business, a flourishing fan community began drawing and trading dôjinshi (self-published comics and zines) based on their favorite characters. Publishers produced sub-culture magazines and direct-to-video animation for the fan market, and the fans, aka otaku, became Japan’s equivalent of hard-core comic book collectors. But for most readers, manga were simply a part of their everyday lives, something they enjoyed casually, like movies or TV.

In the mid-1990s, the Japanese economy went into a recession, which affected manga as well. Sales dipped, and publishers were forced to rely more heavily on licensing, as well as finding new niche markets: video game manga, pachinko manga, Boys’ Love manga. As everywhere around the world, the rise of the Internet and other new technologies changed reading and buying habits; newsstand magazine sales slumped. Publishers fretted about a rise in tachiyomi (reading manga in the store without buying it), mawashiyomi (loaning manga to your friends), used-book chains, and all-you-can-read manga cafés. But graphic novel sales remain strong; in 2002, the latest volume of the manga series One Piece broke records with an initial print run of 2.52 million copies. In Tokyo today, subway commuters may carry more cell phones than manga magazines, but comics are still more widely read and respected in Japan than anywhere else in the world.

MANGA IN AMERICA

American comics had their day in the sun. In the 1930s, newspaper comic strips such as Dick Tracy, Little Orphan Annie, and Li’l Abner featured long, melodramatic stories and were read by millions of people of all ages. In 1934, comic books were invented (originally as reprint collections of newspaper strips), and for years they enjoyed incredible popularity, with genres such as crime, Westerns, superheroes, romance, humor, and science fiction. But by 1954, the violent content of horror and crime comics attracted unwelcome attention from a public anxious about juvenile delinquency. The Seduction of the Innocent, a bestselling book by psychiatrist Fredric Wertham, claimed that comics exposed children to sex and violence (arguments that would be repeated fifty years later about video games). After a public backlash, the surviving publishers instituted strict self-censorship, limiting comics to superheroes and other “safe” entertainment. Over the next twenty years, comics gradually regained their sophistication, but they never recovered their sales or public image.

Meanwhile, in Japan, manga were booming. As early as the 1970s, a tiny number of outlets imported untranslated manga for American buyers, most of whom were already familiar with Japanese styles from watching early anime such as Astro Boy on American TV. With the first appearance of mass-market VCRs in 1975, American anime fandom began to grow. Frederik Schodt’s 1983 Manga! Manga! The World of Japanese Comics was the first English-language book on the subject. By the early 1980s, manga artists such as Monkey Punch and Osamu Tezuka had appeared to small but enthusiastic groups at American comic book conventions, but almost no manga had been translated, except for a few short stories and English-language vanity projects printed overseas. To the vast majority of Americans, “comics” were full-color superhero stories. Black-and-white, foreign comics were not even on the radar.

Then, in the mid-1980s, American comics stores experienced the “black-and-white boom”—a sudden interest in black-and-white, small-press comics, based on the explosive success of the self-published Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles. In this more receptive environment, two separate companies produced the first serious translated manga in 1987: First Comics with Lone Wolf and Cub, and Viz/Eclipse with several titles: Area 88, Mai the Psychic Girl, and The Legend of Kamui. Founded by Seiji Horibuchi with Satoru Fujii as editor in chief, Viz was the U.S. branch of the Japanese manga publisher Shogakukan. For its first releases Viz formed a partnership with Eclipse Comics, an American small-press comics publisher, whose employee James Hudnall had previously written to Shogakukan encouraging them to enter the American market. Toren Smith, another early manga fan, helped get Viz off the ground, then went on to found Studio Proteus, a major manga translation and localization company. Viz later parted ways with Eclipse, while Smith’s Studio Proteus (who did work for both companies) went to Dark Horse Comics and built their manga division.