Excerpt

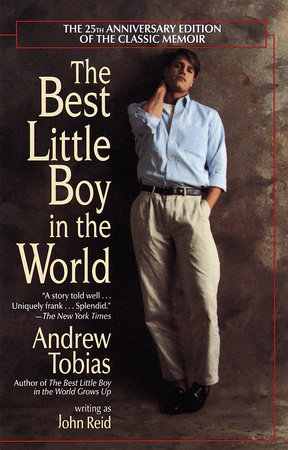

The Best Little Boy in the World

CHAPTER 1

I was eighteen years old when I learned to fart. You may think it’s easy for me to write a disgusting thing like that. It’s not. If someone had told me on that occasion seven years ago—well, of course, no one was around at the time, I would never have done it in anything but the strictest privacy—but if someone had told me that seven years later I would write a book which began that way … the point is, you have no idea how far I’ve come in seven years.

But this will only make sense if I begin at the beginning.

I am wearing a sheet with a hole cut out for my head and holes for my arms. I am carrying a shopping bag that was empty when my mother gave it to me. It has some bite-size Tootsie Rolls in it now, and some white-yellow-orange waxy candies, too. I am not sure what is going on. It seems naughty, and it’s past my bedtime, but Mrs. Connell is driving the car, so how can it be naughty? I am the last one into the station wagon this time. She lifts the gate of the wagon, checks to see that no fingers get caught as she shuts it, but she does not put up the back window. We always put up the back window of our station wagon when anyone is in the back, but Mrs. Connell doesn’t want to put it up and down every time we stop.

I wonder whether I am allowed to eat any of the Tootsie Rolls. They haven’t said, so I’d better not. The car starts forward; I fall out the back window onto the dirt road, thunk, in the darkness, alone. I am not the kind of little boy likely to be missed in a car with a dozen screaming children. I don’t scream.

I am lying on my back on the dirt road, dazed, beginning to wonder what I am supposed to do, beginning to wonder what they will do to me, if they find me, for doing such a bad thing.

I see the car stop up the road. Another ghost has seen me fall out the back window and has passed the word up to Mrs. Connell. Mrs. Connell backs the car up slowly. I am sitting up now, dirt on my sheet, dirt on my hands and in my hair. I am not supposed to be so dirty.

It doesn’t occur to me to move from the middle of the road. I assume that Mrs. Connell won’t run me over. She doesn’t. She checks me all over to make sure I am all right, puts me back in the car, and rolls up the window.

I hope she won’t tell my parents.

I am in the hall closet, behind the winter coats, stifling hot, but this is the price you pay to win at hide-and-seek. We don’t often have enough children around to play hide-and-seek, but when we do, I usually hide here. Someone may open the closet door and look inside, but I just hold my breath behind all those coats, and even if they thrash around the coats, they never find me. It is pitch black with no light fixture inside and poor lighting outside. Only when the television is on is there any light in the closet, and that is because the television is set in the wall, with the back in the closet and the front in the den. I like watching TV backwards, through a crack in the grating behind the picture tube. Today the television is not on. What am I thinking about there in the dark, my open eyes as good as shut?

I am five years old. I am the best little boy in the world, told so day after day. The worst thing I have done to date is to consider—just to consider—ripping off the mattress tag that says DO NOT REMOVE THIS TAG Under Penalty of Law. At five, the best little boy in the world can read that, but somewhere he has heard the unique zrzrzrzippp that ripping off this appendage makes. It’s a louder sound than such a small, soft piece of material deserves to make, and so of particular interest.

I would love to zrzrzrzippp that stupid tag right off; it just invites mischief, hanging there as it does. What good does it do, anyway? It’s our mattress, isn’t it? It is inconceivable that policemen or judges would ever enter the house of the best little boy in the world, whose parents are, by implication, the best—Wait! Maybe they would enter to go after my big brother! Maybe I can zrzrzrzippp the tag off his mattress, and they will come and get him—but that is too much to hope for. And when the Law comes and looks down at me and asks—just a matter of routine questioning, mind you, not grounded in any particular suspicion—“DO YOU KNOW ANYTHING ABOUT THIS?”—I will immediately break down and confess. The BLBITW can bring himself secretly to consider ripping off a stupid tag, but he cannot consider lying.

Five years old. My father is painting the front door of our early American house in Brewster, New York. We go there every weekend, a million miles from anyone else anywhere near my age, except my brother, nine, who alternately terrorizes and ignores me. Being ignored, of course, is the worse of the two.

My father and I are painting the front door. That is, he paints; I am there to run errands. I am never allowed to paint or saw or hammer. I ask my mother what I should do—I’m bored. “Go help your father.” He lets me run errands, which I hate. Or, “Go help your mother.” She lets me set the table, which I hate. My brother loves to set the table, to make me look bad.

The only other member of my family is Sam, the Airedale, who has rough, kinky hair, which I don’t like, and who is about as big as I am. That’s something my brother and I fight about: whose turn it is to feed the dog. Poor Sam. We take the frozen leaves and the ice out of his black metal pot, too large and hardware-storish to be called a bowl, and spoon out some cold corned-beef-hashlike stuff from the can. I don’t know how Sam puts up with it day after day.

Father is painting the door white. Sam and I are watching, standing on the lawn in front of the house. Father goes off to the barn to get something—it must be too high for me to reach or too much fun or something—and I wander around the flagstone path from the driveway looking for ants to squoosh. (No one has ever told me not to do that.)

Father returns, and he is mad. I take my father very seriously, as I suppose most five-year-olds do, and if he is mad, I am scared.

But what have I done? The ants? The mattress-tag thoughts, somehow overheard? He points to the lawn, which now has white splotches all over it. I didn’t do that! Honest! Nonetheless, I feel guilty. I always feel guilty. I break guiltometers.

“It wasn’t that way when I went to the barn. Who else did it if not you?” he asks. True, there is not another little boy for miles, and the evidence is unmistakable. I am being framed.

I didn’t do it, I persist. That gets him considerably madder. Now we are talking not about mischief, but about honesty. And if there is one thing …

My defense department computer should be calculating the probability-weighted payoffs of alternative courses of action along my decision tree, considering sunk and relevant costs, and determining the only rational course of action: Admit guilt and be done with it. Only F. Lee Bailey could advise a plea of not guilty. However, as I am five, I don’t know anything about computers or decision trees, and F. Lee Bailey is still in law school dreaming of the publicity that will come from winning impossible cases like mine. Okay, Dad; I did it. I’m sorry.

Are you kidding? No way! I have an absolute sense of right and wrong, and I am not going to lie, no matter what the consequences, particularly when lying means admitting that I did something wrong, for heaven’s sake, and jeopardizing my status as the best little boy in the world.

I DIDN’T DO IT! I am screaming now. Tears will appear shortly.

Come in the house. Mother comes to watch. She usually rescues me. (I don’t mean to exaggerate: Spankings are as far as it ever goes, and they are rare—of course, I rarely do anything to warrant a spanking.) But honesty is a lesson she feels I must learn.

There we are: I suspended over the ottoman, backside up, yelling that I didn’t do it, honest; Father whacking me and telling me in his strongest language—“FOR CRYING OUT LOUD” is his ultimate profanity—that the paint means nothing, but lying to your parents, for crying out loud, is intolerable; Mother thinking to herself how much more it hurts them than me and preparing for the reconciliation. I don’t know where my brother is. Probably working on the Sunday Times crossword puzzle, or setting the table. Sam is absent also.

I go crying, howling, wracked with the injustice of it all, suddenly tuned in to mankind’s suffering through the ages, stumbling, stamping, stomping to my room.

Somewhere beneath the tears I am still a smart, self-centered little kid, and I half realize, anyway, that I am playing this thing for all it’s worth. Still, this is the kind of injustice and frustration I have heretofore experienced only at the hands of my enormous nine-year-old brother, “Goliath.” That the Supreme Court should suddenly turn against me—the Court upon which the legitimacy of my standing as the best little boy in the world depends (Goliath is the best little bit bigger boy in the world, in case you are wondering how they get around that)—well…. My mouth is full of the pillowcase I have been gnawing. I can say no more.