Excerpt

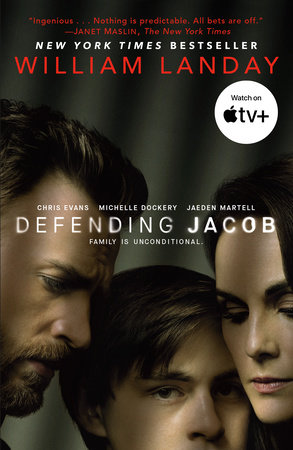

Defending Jacob (TV Tie-in Edition)

1 | In the Grand JuryMr. Logiudice: State your name, please.

Witness: Andrew Barber.

Mr. Logiudice: What do you do for work, Mr. Barber?

Witness: I was an assistant district attorney in this county for 22 years.

Mr. Logiudice: “Was.” What do you do for work now?

Witness: I suppose you’d say I’m unemployed.

In April 2008, Neal Logiudice finally subpoenaed me to appear before the grand jury. By then it was too late. Too late for his case, certainly, but also too late for Logiudice. His reputation was already damaged beyond repair, and his career along with it. A prosecutor can limp along with a damaged reputation for a while, but his colleagues will watch him like wolves and eventually he will be forced out, for the good of the pack. I have seen it many times: an ADA is irreplaceable one day, forgotten the next.

I have always had a soft spot for Neal Logiudice (pronounced la-JOO-dis). He came to the DA’s office a dozen years before this, right out of law school. He was twenty-nine then, short, with thinning hair and a little potbelly. His mouth was overstuffed with teeth; he had to force it shut, like a full suitcase, which left him with a sour, pucker-mouthed expression. I used to get after him not to make this face in front of juries—nobody likes a scold—but he did it unconsciously. He would get up in front of the jury box shaking his head and pursing his lips like a schoolmarm or a priest, and in every juror there stirred a secret desire to vote against him. Inside the office, Logiudice was a bit of an operator and a kiss-ass. He got a lot of teasing. Other ADAs tooled on him endlessly, but he got it from everyone, even people who worked with the office at arm’s length—cops, clerks, secretaries, people who did not usually make their contempt for a prosecutor quite so obvious. They called him Milhouse, after a dweeby character on

The Simpsons, and they came up with a thousand variations on his name: LoFoolish, LoDoofus, Sid Vicious, Judicious, on and on. But to me, Logiudice was okay. He was just innocent. With the best intentions, he smashed people’s lives and never lost a minute of sleep over it. He only went after bad guys, after all. That is the Prosecutor’s Fallacy—They are bad guys because I am prosecuting them—and Logiudice was not the first to be fooled by it, so I forgave him for being righteous. I even liked him. I rooted for him precisely because of his oddities, the unpronounceable name, the snaggled teeth—which any of his peers would have had straightened with expensive braces, paid for by Mummy and Daddy—even his naked ambition. I saw something in the guy. An air of sturdiness in the way he bore up under so much rejection, how he just took it and took it. He was obviously a working-class kid determined to get for himself what so many others had simply been handed. In that way, and only in that way, I suppose, he was just like me.

Now, a dozen years after he arrived in the office, despite all his quirks, he had made it, or nearly made it. Neal Logiudice was First Assistant, the number two man in the Middlesex District Attorney’s Office, the DA’s right hand and chief trial attorney. He took over the job from me—this kid who once said to me, “Andy, you’re exactly what I want to be someday.” I should have seen it coming.

In the grand jury room that morning, the jurors were in a sullen, defeated mood. They sat, thirty-odd men and women who had not been clever enough to find a way out of serving, all crammed into those school chairs with teardrop-shaped desks for chair arms. They understood their jobs well enough by now. Grand juries serve for months, and they figure out pretty quickly what the gig is all about: accuse, point your finger, name the wicked one.

A grand jury proceeding is not a trial. There is no judge in the room and no defense lawyer. The prosecutor runs the show. It is an investigation and in theory a check on the prosecutor’s power, since the grand jury decides whether the prosecutor has enough evidence to haul a suspect into court for trial. If there is enough evidence, the grand jury grants the prosecutor an indictment, his ticket to Superior Court. If not, they return a “no bill” and the case is over before it begins. In practice, no bills are rare. Most grand juries indict. Why not? They only see one side of the case.

But in this case, I suspect the jurors knew Logiudice did not have a case. Not today. The truth was not going to be found, not with evidence this stale and tainted, not after everything that had happened. It had been over a year already—over twelve months since the body of a fourteen-year-old boy was found in the woods with three stab wounds arranged in a line across the chest as if he’d been forked with a trident. But it was not the time, so much. It was everything else. Too late, and the grand jury knew it.

I knew it too.

Only Logiudice was undeterred. He pursed his lips in that odd way of his. He reviewed his notes on a yellow legal pad, considered his next question. He was doing just what I’d taught him. The voice in his head was mine: Never mind how weak your case is. Stick to the system. Play the game the same way it’s been played the last five-hundred-odd years, use the same gutter tactic that has always governed cross-examination—lure, trap, f**k.

He said, “Do you recall when you first heard about the Rifkin boy’s murder?”

“Yes.”

“Describe it.”

“I got a call, I think, first from CPAC—that’s the state police. Then two more came in right away, one from the Newton police, one from the duty DA. I may have the order wrong, but basically the phone started ringing off the hook.”

“When was this?”

“Thursday, April 12, 2007, around nine a.m., right after the body was discovered.”

“Why were you called?”

“I was the First Assistant. I was notified of every murder in the county. It was standard procedure.”

“But you did not keep every case, did you? You did not personally investigate and try every homicide that came in?”

“No, of course not. I didn’t have that kind of time. I kept very few homicides. Most I assigned to other ADAs.”

“But this one you kept.”

“Yes.”

“Did you decide immediately that you were going to keep it for yourself, or did you only decide that later?”

“I decided almost immediately.”

“Why? Why did you want this case in particular?”

“I had an understanding with the district attorney, Lynn Canavan: certain cases I would try personally.”

“What sort of cases?”

“High-priority cases.”

“Why you?”

“I was the senior trial lawyer in the office. She wanted to be sure that important cases were handled properly.”

“Who decided if a case was high priority?”

“Me, in the first instance. In consultation with the district attorney, of course, but things tend to move pretty fast at the beginning. There isn’t usually time for a meeting.”

“So you decided the Rifkin murder was a high-priority case?”

“Of course.”

“Why?”

“Because it involved the murder of a child. I think we also had an idea it might blow up, catch the media’s attention. It was that kind of case. It happened in a wealthy town, with a wealthy victim. We’d already had a few cases like that. At the beginning we did not know exactly what it was, either. In some ways it looked like a schoolhouse killing, a Columbine thing. Basically, we didn’t know what the hell it was, but it smelled like a big case. If it had turned out to be a smaller thing, I would have passed it off later, but in those first few hours I had to be sure everything was done right.”

“Did you inform the district attorney that you had a conflict of interest?”

“No.”

“Why not?”

“Because I didn’t have one.”

“Wasn’t your son, Jacob, a classmate of the dead boy?”

“Yes, but I didn’t know the victim. Jacob didn’t know him either, as far as I was aware. I’d never even heard the dead boy’s name.”

“You did not know the kid. All right. But you did know that he and your son were in the same grade at the same middle school in the same town?”

“Yes.”

“And you still didn’t think you were conflicted out? You didn’t think your objectivity might be called into question?”

“No. Of course not.”

“Even in hindsight? You insist, you—Even in hindsight, you still don’t feel the circumstances gave even the appearance of a conflict?”

“No, there was nothing improper about it. There was nothing even unusual about it. The fact that I lived in the town where the murder happened? That was a good thing. In smaller counties, the prosecutor often lives in the community where a crime happens, he often knows the people affected by it. So what? So he wants to catch the murderer even more? That’s not a conflict of interest. Look, the bottom line is, I have a conflict with all murderers. That’s my job. This was a horrible, horrible crime; it was my job to do something about it. I was determined to do just that.”