Excerpt

The Queen of Tuesday

Nightfall, the Beach at Coney IslandA cloud lifts, and look—here’s Manhattan, tiara-bright and brash, American initiative written in glitter. It’s 1949. Hundreds of cars are driving from the city to the sea. Cadillacs and Packards and wood-bodied Fords. Snaking along Stillwell Ave, they stretch a tail for miles under a Warner Bros. sky.

People are coming in the tangerine twilight to view a collapse.

Hey, that’s your favorite celebrity over there. On the boardwalk, her white shoes scuffed black with sand. (If she’s not famous now, just wait.) She’s striding—confidenting—right into this party. And into the elation of this party. Banners promise or warn A Night You’ll Remember. Walking beside the actress, her husband raises his fist. She isn’t really sure he’s joking.

Earlier, she’d been angry enough to throw a glass; he’d smashed her compact. Your typical knock-down-drag-out. Her husband’s not quite famous yet, either.

And the actress certainly will remember this night. There’s a boy in suede gloves who’s botching it, failing to reach her. The gloves are lemon-colored: it’s a bright-colored time. Tonight, the actress will drop into trouble and watch the sparks in their upward flight. And her husband’s fists will be used in earnest.

For now, the husband mopes. “It’s no good you keep insulting me,” he says, his accent having its way with the words. “I have to know this ‘torch’ expression. Can you explain ‘carry a torch’?”

She says, “Just a habit men have of walking around on fire.” You recognize her—a woman who’s learned the score. “Burning yourself, getting singed, like that.”

Another banner: A Party for the Ages—Elizabeth Trump & Son.

The actress feels chilly. That’s Coney Island in April for you. She’s also frustratingly unseen. The actress has bumped through life knowing what it is to be ignored, even by quote “loved ones.” At tonight’s party, she wants to be noticed by the husband she loves. But also, especially, by men she doesn’t.

First she has to push her way to the boldface names at the water. It surprises her, a little, how the confident can darken a big, open beach.

Partygoers have thronged to the tide line and the first pleats of brown sand. It’s like a religious ceremony where the theologics have been erased. These people are here to worship themselves. That’s only natural. Americans in this little breather from history stand pretty much alone on a cindered map. Every house needs a Westinghouse. The ad style is peppy, with pep and sincerity intertwined. Relax in casual slax. Make a date with Rocket 8. Across the country: fresh purchases and attitudes, fresh beliefs. Plus, it’s been sunny all year and the perfect song is always playing, at just the right volume.

The actress and her husband start down the sand.

In this moment, there is no city but New York City. The long Atlantic keeps pulse at the shore here. It’s glamorous. The air’s strung with laughs and the rattle of sequins, popping flashbulbs. But the actress has a problem now. Her last-chance break is simply not happening.

She doesn’t consider taking her husband’s hand. Nor has he offered it. “On important nights, you louse things up,” he says. “Many times I just do not get you.”

“Hey, that’s my line. You always make me come get you.”

She—or the woman she has trained herself to be—is a bit excessive when not the center of attention. The high, provoking brows; bright hair pinned and lifted off the neck.

“Don’t snap your cap, sweetie,” the actress continues. “When I accuse you for real, you’ll know.”

The kid wearing lemon-suede gloves has to run over and tell the actress about the destruction that’s coming. It’s his actual job tonight. But will the kid reach her? His path across the boardwalk is choked by tuxedoed waiters and linen tabletops. The actress even from this distance is a woman of sedan curves, fantastic. Legs he’d want to die between. The kid’s driven by intensities he had no idea were in him.

“Good luck,” the actress tells her husband. “So remember, the plan is— Hey, wait a second.”

The husband piles ahead; he pretends not to hear. All around, partygoing women contemplate the beach, shoes in hand. And the actress is alone.

This is a party with a political purpose. As is the custom at such parties—the shifts of bigwigs and schemes—the biggest and most important have together made their own scrum. The actress watches her husband jostle toward these fancy people, and she—

She feels somebody’s stare. On her mouth, neckline, her throat. She moves a protective hand over the dimple in her collarbone. And keeps it there. Fingers on two hard dots.

It’s the kid with the lemon-suede gloves: “Miss Puente!” He comes straight up. “Martha Puente, right?”

She stops walking.

“You know, the world’s never seen a destruction party before, miss.” The kid gleams with the importance of any teen given a duty. He recites his statement: “Ready, Martha—may I call you Martha?— er, ready to destroy the world?”

The kid, and with good reason, keeps calling her Martha Puente. Martha Puente is not her name.

She knows what’s what tonight. The man hosting this party wants to get something obliterated. The actress is here to get something made.

She isn’t Martha Puente, any more than she’s Diane Belmont or Montana Hearn. With those names, she’d been trying to catch something she’d almost found.

The kid’s saying, “I mean, destroy metaphorically. It’s gonna be a hoot. Because . . .”

What a time to be left alone here. She’s just schlepped back from Hollywood. Nightmarish trip! Los Angeles: a shuffle of faces and studio commands. Instructions about eyebrows, diction, about posture. Also about not falling for nice ethnics. She had been run through a showbiz machine that existed, far as she could tell, to conventionalize the neck length of swans for better sale to a nation of ducklings. (She’d sat through studio reprimands with parted lips and just listened.) But MGM terminated her contract last month. She’d failed as a movie star.

“Miss Puente?” The kid’s scratching at a puberty cluster on his cheek.

The actress gives her smile of special elegance anyway. (Her beauty can still draw a gasp when she smiles, when she pouts.) But after twenty bit-part years, although still kind of young, she’s also probably washed up.

Another bad break: It looks as if her husband is holding back to chat with Nanette Fabray, of all people. Goddamn him. Nanette Fa-bare-ass?! Now?

But hang on a sec.

Instead of quitting and slinking back upstate—where the cold Chautauqua always springs tears from her face—after silently admitting, It’s over, I’ll never achieve, and also my husband’s talking to a harlot not ten yards from me, instead she surprises herself.

“A hoot?” she says. She often surprises herself. “Kid, parties are for single women and cheating men. When you die, you’ll regret the things you did when you could’ve been home relaxing. Nice gloves. The name’s not Martha Puente.”

And her brazen right eyebrow rises just a little.

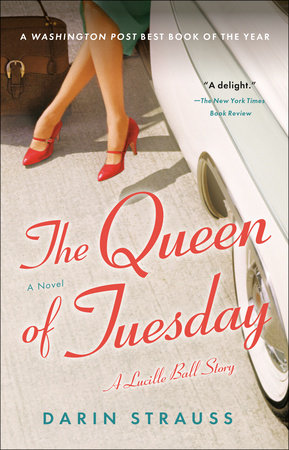

“The name,” she says on this April night two years, six months, and four days before her triumph, “is Lucille Ball.”

. . .

Maybe it’s just an innocent little chat there across the beach with Lucille’s husband and Nanette Fabray?

Looking over, she doesn’t notice that the kid with the gloves’s face has gone red. She’d done a few wartime “Martha Puente” spreads for

Yank magazine, the Army publication. (The G.I.s had had fun with the centerfold, with the word Yank itself, General Ike’s hairy-palms-and-blindness campaign.) The kid’s standing here smitten, having kept that photo under his mattress all through junior high.

He doesn’t know what to do. Say something to her.

“It was only that . . .” He hunts around his brain for a suave line. “It was I could see right off you’re uh . . .” (Being an adolescent means running this kind of vain scavenger hunt every day.) “I guess I don’t know what you mean. You’re not Martha Puente?”

Lucille brought her hand to his shoulder.

“Kid, I’m in show business.” She smiles right at him. “I don’t mean a thing.”