Excerpt

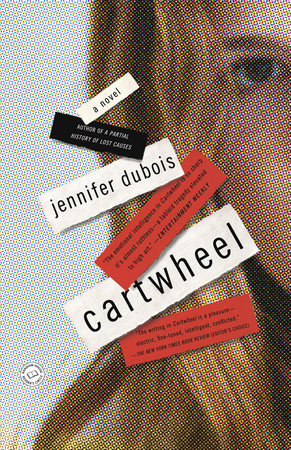

Cartwheel

CHAPTER ONE

February

Andrew’s plane landed at EZE, as promised, at seven a.m. local time. Outside the window, the sun was a hideous orb, bleeding orange light through wavering heat. Andrew was still woozy from his two Valiums and two glasses of wine, the bare minimum that he needed to fly these days—to anywhere, for anything, though especially for here, for this. The irony of being a professor of international relations who was terrified of international travel was not lost on him (no irony was lost on him, ever), but it could not be helped. Neither could it be mitigated by the knowledge—always understood but now finally believed—that the things that go wrong are rarely the things you’ve thought to worry about.

Andrew patted Anna on the shoulder and she roused herself. He watched her forget and then remember what was happening. He was glad he didn’t have to remind her. She pulled her iPod headphones out of her ears, and Andrew caught snatches of some ambient, low-key music—the music of the day was so bloodless, he often thought: Didn’t these kids want anything, and weren’t they mad at anybody?—before she thumbed it quiet. Anna had endured the trip reasonably well—her sensible hair was limp in a ponytail; her nautical stripes, so favored by his students these days, were barely creased. She wore her competence lightly. She didn’t know how terrifying it was to him.

“Dad,” she said. “You need to blink.”

Andrew blinked, painfully.

“Does your corneal abrasion hurt?” she said.

“No,” he said. It always hurt. He had poked himself in the eye during class one day—while making a particularly vigorous point about Russian cyber-terrorism in Estonia—and he’d had to go to the ER for a local eyeball anesthetic. Now his eye hurt every morning, every flight, every time he was tired or stressed, which he always would be, now, for the foreseeable future.

“Will we see Lily today?” said Anna.”

Andrew licked his lips. His eyeballs were so dry that he thought they might tear. The Argentina flights from the East Coast went only once a day, and only from D.C., and it was impossible to get to D.C. in less than seven hours, no matter how you looked at it. Andrew could not, he reminded himself, have gotten here any earlier. “Probably not today,” he said.

“Will Mom see her when she comes?”

“Hopefully.” Andrew’s voice cracked, and Anna looked at him, alarmed. “Hopefully,” he said again, to show her that the crack had been fatigue, not emotion.

Outside, it was summer, as Andrew had known—but secretly not entirely believed—that it would be. Anna shimmied out of her jacket, her nose crinkling at the smell of gasoline. Inside the airport, the terminal thrummed with travelers. Andrew offered to buy Anna a soda, then rescinded this offer when he spotted the newspaper outside the kiosk—he didn’t have much Spanish beyond what one absorbed through cultural osmosis and a general familiarity with Latinate words, but it was uncomfortably easy to get the gist of the headlines, whether he wanted to or not. Andrew wished desperately to keep Anna away from the newspapers. She knew the contours of the accusation, of course, but Andrew had managed—or thought he’d managed—to protect her from the worst of it. The coverage was only just beginning to leak over to the United States, anyway, and Andrew had spent long hours on the Internet looking for the stories: the depictions of Lily as hypersexual, unstable, amoral; the lurid intimations about her romantic jealousy and rage; the accounts of her smug and towering atheism. The fact that she hadn’t cried—not after Katy was killed and not during the interrogations, either (the Internet had harped on this so much that Andrew had found himself shouting “She’s not a crier! She’s just not a fucking crier!” into the computer). And finally, the worst, most militantly misunderstood information of all: the fact that a delivery truck driver had seen Lily running from the house with blood on her face the day after the murder. No matter that she’d been the one to find Katy; no matter that she’d been the one to kneel over her and try to administer brave and futile CPR. The news reporters weren’t bothering with that information, and Andrew didn’t expect them to start. He was beginning to understand what story they were trying to tell.

Announcing that the sodas would be better outside the airport, Andrew maneuvered Anna (rather deftly, he thought) toward baggage claim, where they waited for fifteen minutes in silence. In wrestling the suitcase off the conveyer belt, Andrew accidentally stomped on the foot of an androgynous teenager.

“Permiso,” he muttered to the teenager, who was wearing a T-shirt that said SORRY FOR PARTYING. Beside him, Andrew could feel Anna stiffen; Andrew liked to at least know how to apologize wherever he went, but Anna hated it when he tried to speak any language other than English. Two summers ago, in a different lifetime, Andrew had spent three months doing research in Bratislava—his area was emerging post-Soviet democracies, though his job got a little less interesting the more fully the democracies emerged—and afterward the girls had met him in Prague for a week of castles and bridges and beer. Anna had flinched every time he opened his mouth to deploy some phrase he remembered from his three semesters of college Czech. “Dad,” she’d said. “They speak English.” “Well, I speak Czech.” “No. You don’t.” “It’s polite to address people in the local language.” “No. It’s not.” And so on. Lily, on the other hand, had made him teach her as much Czech as he could, and had then thrown it around willy-nilly—mispronounced, absurd, chirping informal greetings at storekeepers who tended to smile at her, even though she was basically insulting them, because she was so obviously well-intentioned. Andrew used to imagine that Lily’s general goodwill, the buoyancy with which she addressed her life, was easily detectable by all people of the world, and that it would protect her. It seemed now that this was not the case.

In the taxi, Andrew and Anna passed fruit stands, dingy-looking bars, backfiring motor “cycles. Through the hazy heat, Andrew saw barrios with squat, intersecting systems of housing; clotheslines shimmering with brightly colored clothes; the occasional corrugated tin roof winking astral-bright in the sun. The roads were medium-good; the infrastructure in general seemed decent. Out the window, Andrew saw satellite dishes wedged improbably between houses, looking like the detritus of abandoned spaceships. He saw a large compound, walled and razor-wired, manned by two security guards with walkie-talkies. He craned his neck to see if it was the prison, but it turned out to only be a housing development.

“Nothing’s open,” said Anna. She was looking out her own window and did not turn around.

“It’s Sunday,” said Andrew. “Very Catholic country.”

“It’s too bad that Latin America isn’t your area.”

Andrew stared at the back of Anna’s head. She had lately taken to making inscrutable declarative statements in studied neutral tones. Andrew desperately hoped that this was not the onset of irony.

“You might get some work done, I mean,” she said.

“I don’t know about that.” Andrew was suddenly nauseous, awash with their strange new calamity. There was, of course, no possibility that Lily had actually been involved in any of this; Andrew’s confidence on that point was part of what had made the situation seem, initially, not catastrophic. The accusation was so ghastly and so wild and so patently, transparently, ludicrous that he’d nearly laughed when he first heard of it. Not that there weren’t a few things he could imagine Lily getting justly arrested for. Before she had left, he and Maureen had had a series of sober conversations with her—about the harshness of Latin American drug laws, mostly, as well as the laxity of Latin American sexual safety standards. They’d sent her off with an enormous box of Trojans—industrial-sized, Andrew thought, issued for health clinics or music festivals, no doubt; a box that size could not possibly be intended for the use of a single human being. Andrew reeled to think of how much sex his daughter would have to have to run through all of them. Nevertheless, he had bravely and maturely had the conversation, alongside Maureen (such was their commitment to pragmatism! such was their commitment to co-parenting!), and then bravely and maturely sent Lily off with the box. And Andrew had worried about Lily constantly—he worried about her being kidnapped, trafficked, impregnated, sexually assaulted, afflicted with some horrible STD, arrested for marijuana use, converted to Catholicism, wooed by a long-lashed man with a Vespa. He worried she’d make too few friends, then he worried she’d make too many. He worried that her GPA would suffer. He worried about her bug bites. He worried so much that when there came a call from Maureen—on his work phone in the middle of the day, her voicemail left in a strangled half whisper—Andrew could taste metal in his mouth, so certain was he that something life altering had happened. And when he heard Lily was in jail, his mind flooded with grim visions of drug use and anti-Americanism and political points to be scored. He could imagine how she’d look to everyone (naïve, and entitled, no doubt), and he could easily imagine the incentive for punishing her harshly.