Excerpt

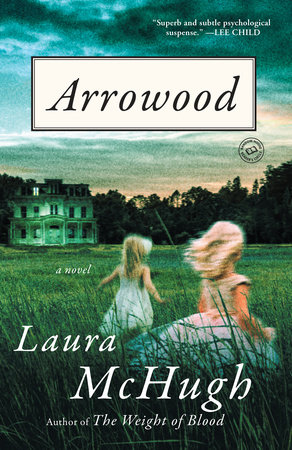

Arrowood

Chapter 1

I used to play a game where I imagined that someone had abandoned me in a strange, unknown place and I had to find my way back home. There were various scenarios, but I was always incapacitated in some way—tied up, mute, missing a limb. I thought that I could do it blind, the same way a lost dog might trek a thousand miles to return to its owner, relying on some mysterious instinct that drew the heart back to where it belonged. Sometimes, in the towns where I’d lived after Keokuk, in a bedroom or classroom or while walking alone down a gravel road, I’d pause and orient myself to Arrowood, the Mississippi River, home. It’s there, I’d think, knowing, turning toward it like a needle on a compass.

Now, as I crossed the flat farmland of Kansas and northern Missouri, endless acres of wheat and corn blurring in the dense heat, I felt the road pulling me toward Iowa, as though I would end up there no matter which way I turned the wheel. I squinted into the bright afternoon sky, my sunglasses lost somewhere among the hastily packed bags and boxes I’d crammed into the back of my elderly Nissan. It was late September, the Midwestern air still stifling, unlike the cool sunshine I’d left behind in Colorado, where the aspens had just begun to turn.

Back in February, when I was still on track to finish my master’s degree, my recently remarried mother had called to let me know that my dad, Eddie, had keeled over dead on a blackjack table at the Mark Twain Casino in LaGrange. I hadn’t heard from my dad in the months leading up to his death, and hadn’t seen him in more than a year, so I had a hard time placing my feelings when I learned that he was gone. I had already lost him, in a way, long ago, in the wake of my sisters’ disappearance, and while I’d spent years mourning that first loss of him, the second loss left me oddly numb.

Still, I’d wept like a paid mourner at his funeral. The service was held in Illinois, where he’d been living, and most of the people in attendance, members of the Catholic parish he’d recently joined, barely knew him. I hated how funerals dredged up every shred of grief I’d ever felt, for the deceased or otherwise, each verse of “Amazing Grace” cutting into me and tearing out tiny bits of my insides. The priest wore a black cape over his cassock, and when he raised his arms to pray, it spread out dramatically, revealing a blood-red lining. He droned on at length, reminding us how much we had in common with the dead: We all had dreams, regrets, accomplishments, people we’d loved and disappointed, and at some point, for each of us, those earthly concerns would fall away, our lives replaced in an instant by darkness or—if you believed—light. Sometimes death came too soon, sometimes not soon enough, and only for certain sinners did it come at a time of one’s choosing.

When he spoke of those who had preceded my father in death, he didn’t mention Violet and Tabitha. Nor did he name them as survivors. My little sisters were neither alive nor dead, hovering somewhere in between, in the hazy purgatory of the missing. I had been the sole witness to their kidnapping when I was eight years old, and I had spent my childhood wondering if the man who took them might come back for me. He was never arrested, and no bodies were ever found.

Dad was buried in Keokuk, at the Catholic cemetery—despite the rift between them, Granddad hadn’t gone so far as to kick him out of the Arrowood family plot—but I didn’t attend the interment. No graveside service had been included in his prepaid burial plan, and my father was lowered into the earth without any last words.

Months later, a lawyer for the family trust called to inform me that Arrowood, the namesake house my great-great-grandfather had built on the Mississippi River bluff, the house we had left not long after my sisters’ abduction, was mine. It had sat empty for seventeen years, maintained by the trust, purposely kept out of my father’s reach to prevent him from selling it. Now I was finally going home.

It hadn’t been a difficult choice to make. Even before I had given up on what was supposed to be my last semester of school, there hadn’t been much tying me to Colorado. I was twenty-five years old, working as a graduate assistant in the history department, and renting an illegal basement apartment, the kind with tiny windows near the ceiling that would be difficult to escape from in a fire. The college fund Nana and Granddad had left for me was close to running out. I sat alone in my room at night staring at blank pages on my laptop, my fingers motionless on the keys, waiting for words that wouldn’t come, the title of my unfinished thesis stark on the glowing screen: “The Effects of Nostalgia on Historical Narratives.” Colorado had never felt like home. I had thought at first that the mountains could be a substitute for the river, something to anchor me, but I was wrong.

With the loss of my dad, the number of people in the world who knew both parts of me—the one that existed before my sisters were taken, and the one that remained after—had dwindled to a terrifying low. I worried that the old me would vanish if there was no one left to confirm her existence. When the lawyer said that Arrowood was mine, my first thoughts had nothing to do with the logistics or implications of moving back to Keokuk and living in the old house alone. I didn’t wonder if the man who had haunted my dreams was still there. I thought of my sisters playing in the shade of the mimosa tree in the front yard, of my childhood bedroom with the rose-colored wallpaper and ruffled curtains. And I thought of Ben, who knew the old me best of all. A sense of urgency flared inside me, electricity tingling through my limbs, and I was dumping dresser drawers onto the bed, pulling everything out of the closet before I had even hung up the phone.

the people of iowa welcome you: fields of opportunities. As I passed over the Des Moines River and saw that sign, my breath came easier, like I’d removed an invisible corset. I had been born at the confluence of two rivers, the Des Moines and the Mississippi, and an astrologer once explained that because I was a Pisces, my life was defined by water. I was slippery, mutable, elusive; like a river, I was always moving and never getting anywhere.

It was strange, crossing into Iowa, that I could feel different on one side of the bridge than the other, yet it was true. Each familiar sight helped ease a bone-deep longing: the railroad trestle, the cottonwoods crowding the riverbank, the irrigation rigs stretching across the fields like metal spines, the little rock shop with freshly cracked geodes glinting on the windowsills. I rolled down the window and breathed the Keokuk air, a distinct mix of earthy floodplain and factory exhaust. The Mississippi lay to my right, and even though I couldn’t yet see it beyond the fields, I could sense it there, deep and constant.

I followed the highway into town, which, according to the welcome sign, had shrunk by a third, to ten thousand people, since I’d moved away. A hundred years before, when riverboat trade thrived on the Mississippi, Keokuk had been hailed as the next Chicago, at one point boasting an opera house, a medical college, and a major league baseball team. A dam and hydroelectric plant were constructed to harness the river, and at the time of their completion in 1913, they were the largest in the world. Later, factories cropped up along the highway, but many had since shuttered their doors, the jobs disappearing with them. What remained as Keokuk faded was a mix of grandeur and decay: crumbling turn-of-the-century architecture, a sprawling canopy of old trees that had begun to lose their limbs, broad streets and walkways that had fallen into disrepair.

The houses grew older and larger and more elaborate as I passed through the modest outskirts and into the heart of town. Block after block of beautiful hundred-year-old homes, no two alike, some well preserved, some badly neglected, others abandoned and rotting into the ground, traces of their former elegance still evident in the ruins.

I crossed over Main Street to the east side, where the road turned to brick and rattled the loose change in my cup holder, reading the familiar street signs aloud as I passed them. Though I’d never driven here on my own, I didn’t need signs to find my way. I turned left onto Grand Avenue, the last street before the river. It had always been the most coveted address in town, and the fine homes were owned by people who could afford their upkeep: doctors like my late granddad, bank presidents, plant managers who had never worked a day on the line.

There were Romanesque Victorians, Queen Annes, Gothic Revivals, Jacobethans, Neoclassicals, Italianates, each house two stories or three, with towers and cupolas and columns. They sat on deep, tree-lined lots, the ones on the east side backing to a bluff two hundred feet above the Mississippi. Illinois forests and farmland stretched into the distance across the river, the occasional church steeple or water tower punctuating an expanse of green.

Two blocks down, I pulled into the driveway at Arrowood and stopped the car, taking in my first view of the house in nearly a decade. I had expected it to seem smaller now that I was grown, the way most things from childhood shrink over time. But Arrowood, built in the heavily ornamented Second Empire style, was as imposing as ever, three stories plus a central tower rising up between two ancient oak trees. Scrolled iron cresting topped the distinctive mansard roof, the tower hiding the widow’s walk at the back of the house where my ancestors had once watched for barges coming down the river. Embedded in the corner of the lawn was a small plaque acknowledging the house as a national historic property and a stop on the Underground Railroad. I pulled forward to park in the porte cochere and got out to wait for the caretaker, who would be showing up to give me the keys.

A bank of dusky clouds had pushed in from the north, the soupy air making me feel as though I had gotten dressed straight out of the bath, my tank top and shorts sticking uncomfortably to my skin. I followed the mossy brick path alongside the house, marveling at the fact that Arrowood appeared not to have aged in my absence; while the flower beds at the side of the house were now empty, and the hydrangeas that once bordered the front porch were gone, I couldn’t tell by looking at the house itself that any time had passed. The wraparound porch was freshly painted, the white spindles and fretwork bright against the dark gray clapboard. The mimosa tree still stretched its impossibly long limbs across the front yard, and I could picture the twins running through the grass, the gold car speeding away. I took a breath, and it was there: the lingering pain of a phantom wound inflicted long ago.

My mother had warned me that it was a mistake to come back, that Arrowood was best left in the past, and if I was smart I’d pray for an electrical fire and a swift insurance payout. I had set foot inside the house only once since we left, and for all the years I’d been away, I’d felt a nagging sense of dislocation. Nostalgia had always fascinated me, the bittersweet longing for a time and place left behind. I’d studied the phenomenon extensively for my thesis, not surprised to learn that nostalgia was once thought to be a mental illness or a physical affliction; to me, it was both. I had loved this house beyond reason, had felt its absence like the ache of a poorly set bone.

From the time we moved away up until I was fifteen years old, I had returned to Keokuk every summer to visit Grammy (my mother’s mother) and my great-aunt Alice at the Sister House a few blocks to the south. I would haunt the sidewalk outside of Arrowood, peeking into the dark windows with my friend Ben Ferris whenever we thought no one would catch us, wishing that I could go inside. Nana gave me a copy of Legendary Keokuk Homes, published by the Lee County historical society, and I had immersed myself in the histories of all the old houses, especially Arrowood. I wasn’t sure anymore how much of what I remembered about the house was actual memory and how much had leached into me from the book and Nana’s stories. Now that I was allowed back in, I was afraid it wouldn’t match the vision in my head, that it would all look wrong. The one time Ben and I had managed to sneak inside—the summer we were fifteen—it had been too dark and we were distracted by more pressing things.

I glanced over at the Ferris house next door, a cream-colored Gothic Revival with steep gables and narrow lancet windows and a handsome brick carriage house beside the drive. Maybe Ben was over there now, close enough to hear me if I called his name. I didn’t know what I would say if I saw him, how I would explain the years of silence.

The breeze picked up, fluttering the delicate fernlike leaves of the mimosa, and a few raindrops specked the front walk as a four-door Dodge truck lumbered into the drive and parked behind my car. The caretaker climbed out, a man about my dad’s age whose copper-colored hair had retreated halfway up his skull, revealing a broad, shiny forehead. His features crowded together at the center of his face, a bit too close to each other, as though they didn’t realize they had room to spread out. He wore tan Carhartt pants and work boots and a navy-blue shirt with the sleeves rolled up to accommodate his thick forearms.

“Miss Arrowood?” He had a raspy voice and a cordial smile. “I’m Dick Heaney. Sorry to keep you waiting.”

“You didn’t, really,” I said. “I just got here.”

“It’s such a pleasure to finally meet you,” he said. “I don’t know if your mother ever told you, but we were good friends back in the day. I knew your dad, too. He was a few years above me in school.”