Excerpt

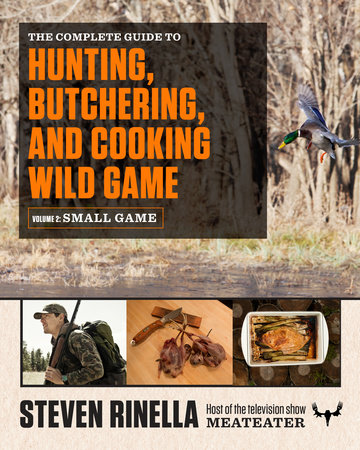

The Complete Guide to Hunting, Butchering, and Cooking Wild Game

Chapter 1

Gear

To kick off the gear section, I’ll refer to one of my own passages from Volume 1 of The Complete Guide to Hunting, Butchering, and Cooking Wild Game: “Gear is like booze. Once you get older, you realize that quality should be regarded more highly than quantity.” That basic sentiment holds true for the small game hunter—save your money and focus on getting yourself into a kit of quality gear rather than cutting corners by buying a bunch of subpar junk that brings you lots of frustration and not much game meat. But I’m happy to say that the hunter can equip himself or herself for a generalist approach to small game for a lot less money than it takes to get rigged up for a generalist approach to big game. The firearms, ammunition, and archery gear for small game are generally cheaper than those intended for big game, and the demands on clothing, backpacks, and cutlery are less severe. The walks tend to be shorter, the animals are smaller, and prime locations are usually a little bit closer to home.

In certain families, equipping a new small game hunter doesn’t cost a dime. When I was a kid, I hunted small game successfully for years without ever touching a new piece of gear. I wore hand-me-down clothes and shot hand-me-down guns. I longed for a brand-spickety-new left-handed semi-auto .22, yet I had to settle for an old right-handed bolt-action rifle that my dad had purchased from a nearby summer camp when they discontinued their marksmanship program. At the time, I was embarrassed about that rifle. But now that I’m approaching middle age, with young kids of my own, those days of making do have become a matter of personal pride to me. That old right-handed .22, a Remington Model 581, remains one of my most treasured firearms. As it turns out, it’s a real tack driver. I intend for it to serve as my son’s first squirrel rifle.

In other words, don’t let cost get in the way of your desire to hunt small game. Resident small game licenses are dirt cheap, you usually don’t need any special tags (with the notable exception of turkey), and you can get a box of fifty .22 rounds for about five bucks. If you learn to be a deadeye with your .22, that equals ten daily bag limits of squirrels in my home state of Michigan. Or, to put it another way, ten family-sized preparations of hasenpfeffer, a sublime and vinegary dish intended for hares that works great with fox squirrels and gray squirrels as well.

When it comes to selecting hunting gear, it’s important to pay attention to the voices of people who have been doing things longer or more successfully than you have. I leaned on the expertise of dozens of talented and dedicated hunters while putting this guidebook together. Their impressions of the gear that I discuss (or choose not to discuss) in this section have certainly colored my own opinions. But understand that my recommendations are just that: recommendations. If something here doesn’t make sense to you, or if your experiences with a certain product or idea contradict my own, then you should go with what makes you feel comfortable.

FIREARMS

A versatile small game hunter should regard his firearms as the foundation of his hunting gear. I wouldn’t say the same for all types of hunting—for versatile big game hunters, apparel and optics are equally as important as firearms. But for small game hunting, it’s absolutely true: guns matter, and they matter a lot.

But don’t go thinking that you need an arsenal of rifles and shotguns in order to be an effective small game hunter. If you own a vault full of shotguns, that’s great, as long as you spend enough time with one of them to learn how to use it. But for you folks who don’t have the money or inclination to accumulate a collection of firearms, don’t fret. By shopping carefully—either used or new—you can purchase a single shotgun that will cover virtually 95 percent of the small game hunting opportunities that this continent has to offer. If you want to bring your level of preparedness up to 100 percent, that can be easily achieved with the addition of a .22- caliber rimfire rifle.

THE SHOTGUN

The coolest thing about shotguns is how inherently versatile they are. In a given year, an enterprising hunter might use his or her shotgun to hunt everything from mourning doves weighing 5 ounces to wild turkeys topping out at 25 pounds. If that same shotgun accepts multiple types of barrels—and many do—it might also be used very effectively for whitetail deer. To achieve this level of versatility with a rifle, you’d need a caliber that was ideal for everything from squirrels to moose. (And trust me, it doesn’t exist.) While it might seem that a versatile shotgun would be costlier than one with a narrower range of capabilities, the opposite is true. Some of the lowest-priced shotguns on the market carry some of the highest credentials. But first, here’s a primer on shotgun terminology and how it applies to you.

Gauge: Shotguns are sized according to the bore diameter. The smallest shotgun used for hunting purposes is the .410 (rabbits and squirrels, typically), while the largest is the 10-gauge (geese and swans). The .410 is named after its caliber measurement; the diameter of the bore is .410 inch, just as a .308 rifle cartridge is .308 inch. Shotguns that use the term gauge, such as 10-gauge, 12-gauge, and 20-gauge, rely on an arcane system that correlates the bore diameter to how many lead spheres of that size it would take to make a pound of weight. A 20-gauge shotgun has a bore diameter of .615 inch, and twenty lead balls of that size would weigh 1 pound. A 12-gauge has a bore diameter of .729 inch; twelve lead balls of that size weigh a pound.

This will piss off a lot of shotgun snobs, including some guys who really know what they’re talking about, but the only two gauges worth considering are 20-gauge and 12-gauge. Ammunition for these gauges is widely available and highly versatile, and there’s no practical reason to stray into the more esoteric gauges. In recent years there’s been a lot of spirited debate about the relative attributes of 12-gauge and 20-gauge shotguns, spurred in particular by advances in ammunition. A person could spend days reading up on these arguments in dedicated firearms magazines, and you’re welcome to do so. But here I’m just going to cut through a lot of the BS and give you a fairly straightforward summation of the information and also a piece of advice. A 12-gauge shotgun has bigger shells than a 20-gauge shotgun, so it throws more pellets and it typically kicks harder. If the bulk of your hunting is going to be for smaller-sized game, such as rabbits, quail, pheasants, et cetera, then feel free to go with a 20-gauge. But if you’re also going to be hunting game that’s a little larger, such as turkeys, ducks, and geese, go with a 12-gauge.

Action: While there are bolt-action shotguns, for practical purposes we’ll limit our discussion here to autoloading, pump-action, and break-open shotguns. Each type has its own selling points and liabilities.

Autoloading shotguns: Sometimes called autoloaders or (incorrectly) automatic shotguns, these harness power from the shotshell in order to eject the spent round, reset the firing pin, and load a new round from the magazine. Autoloaders used to have a reputation for malfunctioning and frequent jamming, but newer models are much more reliable.

Autoloader Pros

•High rate of fire. Every time the trigger is pulled, the gun fires and cycles without the assistance of the operator; most modern semi-auto shotguns will fire as quickly as the shooter is able to pull the trigger.

•Low recoil. Because of gas- or inertia-powered cycling systems that harness some of the recoil energy, the felt recoil of the semi-auto shotgun is less than that of pump-actions and break-opens.

•Ease of follow-up shots. Because the semi-auto shotgun cycles without the aid of the shooter, follow-up shots can be made more efficiently due to the lack of operator movement during shooting.

Autoloader Cons

•Versatility. Due to the various cycling systems in semi-auto shotguns, adjustments must be made to most models when switching between various loads and shell lengths.

•Safety. Due to the tension of the recoil spring, a shooter can injure himself or herself when closing the bolt. Also, unintentional shots can be made if the shooter is unfamiliar with the mechanics of the firearm.

•Difficulty of maintenance and assembly. With the various cycling systems available in semi-auto shotguns, the operator must be familiar with all of the internal workings of the weapon when performing basic assembly and disassembly, making the weapons less user-friendly than pump-actions and break-opens.

Pump-action shotguns: Sometimes known as slide-action shotguns, these are operated by a manually sliding forearm that ejects the spent shell, cocks the firing pin, and loads a new shell from the magazine. The number-one-selling shotgun of all time is the Remington 870, a pump-action shotgun.