Excerpt

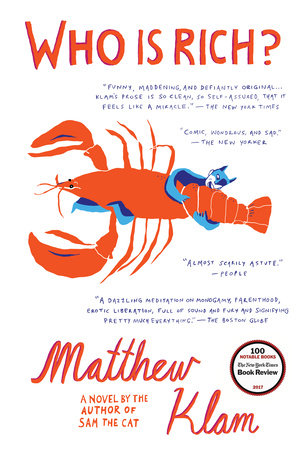

Who Is Rich?

***This excerpt is from an advance uncorrected copy proof***

Copyright © 2017 Matthew Klam

Chapter One

Fog blew in Saturday morning. I sat under a big white tent and drank some coffee while my chair sank into the lawn. I talked to a kid with a heavy beard in a mangled straw hat who last year for some reason we started calling Swaggamuffin.

A girl wearing a name tag passed out rosters to faculty. A guy walking behind her handed me an info packet. I sat there eating toast, looking at my notes. Other people were out there too, chatting and smoking. I said hello to a dozen familiar faces from over the years and drank several more cups. The fog burned off. A lawnmower buzzed. The sky was a flawless aquamarine blue.

I’d written a three-part lecture, on drawing techniques, brain- storming, and plotting, and also found some handouts with exercises from last year or the year before that. We supplied them with pencils, erasers, pens, nibs, brushes, and paper—100-pound acid-free Bristol board for comic applications—and a little plastic thing called the Ames Lettering Guide, which I still had no idea how to use.

We were gathered on the campus of a college you’ve never heard of, at the end of a sandy, hook-shaped peninsula, bound by the Atlantic and scenic as hell. It was my fifth straight summer running a workshop at an annual summer arts conference, and once again my class was full. The conference had begun fifteen years before as a one-day poetry festival and had grown every year in size and popularity, although the college itself had not fared as well. Over time, pieces of it had been boarded up to save money until the entire school was abandoned, then reopened in a limited capacity as a satellite of the nearest state U. The college had kept its name, which was the name of the town, which had been named after the people who’d been here since the beginning of time, who’d made peace with the English settlers, teaching them to fish and hunt, helping them slaughter neighboring tribes, before they too were wiped out by disease or dragged off and sold into slavery.

Nada Klein, with her long French braid and dark wolfish eyes, walked through the tent with her shawl dragging on the ground. She beat cancer every year, and showed up late to her own slide talks, and was widely mocked and imitated. Larry Burris was back, too. He skipped his meds one year and wore a jester’s cap to class and lit his own notes on fire, and had to spend the night in a hospital. He stood beside me now, beneath the tent flap, patiently signing a copy of his book, and handed it back to a woman who hugged him. On the faculty were many friends I’d come to know over the years as intellects, historians, wordsmiths, talented performers, storytellers with big fake teeth, addicts, drunkards, perverts, world-famous womanizers, sufferers of gout, maniacs, liars—embittered, delusional, accomplished, scared of spiders, unable to swim, loveless, and cruel. I noticed Barney Angerman, who’d won the Pulitzer for drama the year I was born, and Tabitha Portenlee, who’d written an acclaimed incest memoir; she was helping Barney through the breakfast line as he gripped her arm. This past winter the conference director had asked me to name another cartoonist I could vouch for to teach a second comics workshop, but I didn’t answer him. I worried, because of the way my career had gone, that I’d be hiring my replacement.

A little before nine I went to the Fine Arts building. Hurrying down a long hall, past students and teachers, I looked for my studio. There were classes in the annex now, landscape photography, felt making, fresco on plaster, whatever that was.

When I got there they were pulling out their stuff, giving each other the once-over. I flipped through my notes. A woman who lived in town was complaining about beach traffic. A skinny kid stared at me, wearing a sundress, mascara, and a pearl choker. A young Asian woman stared at him, clutching her pencil case. A young man in a white polo, a craggy-looking old guy, and a girl with button eyes and tiny feet were talking with affection about their dogs.

I opened the info packet and read the bios of the other teachers and guest speakers printed in the conference pamphlet. There were different levels of us, unknown nobodies and one-hit has-beens, midlist somebodies and legitimate stars. As I read, I could hear my own labored breathing. I tried to slow it down but felt worse, graying as the blood left my brain. I read my course description from who knows when.

CARTOONING STUDIO: SEMIAUTOBIOGRAPHIcAL COMICS

with Rich Fischer

July 18–21. Tuition: $1,500. Ages 18+. For-credit option:

$1,900.

Are you ready to take your cartooning to the next level? Start from scratch, or bring your own comic in progress to our 4-day summer intensive, and we’ll help you do just that. . . .

A murmuring of bodies came from the hall. Fans turned slowly over us. An old galvanized ventilation system snaked around the ceiling. A thin woman stepped cautiously into the room, walked out, then came back in. Wild brown hair, sharp elbows, bony wrists, redness around her mouth, raw, wounded-looking lips, a long skirt, moccasins. Was she the kind of person to take time out of her busy life to make a fictionalized comic about herself? Apparently.

I moved across the studio, faking a slight limp in order to give my movements in flip-flops and canvas shorts a more tweedy gravitas, and adjusted the blinds. In this way I became the parent, the benign elder, with knowledge and some intangible quality of goodness that would allow my students to project onto me the power to contain their aspirations. I’d be the vessel, I’d hold their dreams, whatever. When it was quiet, I asked them to go around the room and introduce themselves.

I wasn’t a teacher. I didn’t belong here. I’d ditched my family and driven nine hours up the East Coast in Friday summer highway traffic so I could show off in front of strangers, most of whom had no talent, some of whom weren’t even nice, while I got paid almost nothing. They’d blown their hard-earned money to come to this beautiful place not to swim or sail but to sit in a room all day writing and drawing their guts out, telling themselves it was a dream come true.

I’d driven up here for the first time the summer after my only book came out. This conference was one of many good things that had come to me in those days. It was maybe the only thing left. Every time I pulled into town and saw the blinking neon lobsters, the bowling alley, the giant plastic 3-D roadside sandwich, it gave me a big feeling, reminding me of a once-limitless future.

Melanie Lenzner taught high school art in New Hampshire and went on too long, acting like it was her class, not mine. Helen Li, a biomolecular engineering student, said she didn’t want to start med school in the fall. Nick, the trans kid, said his father had thrown him out of the house and that he—or she—lived in her car. Carol, faded red hair cut short and stalky, looked alarmed, and asked how long he or she’d been homeless. George had gone into the army at eighteen, had fought in Vietnam, lost his wife twenty years ago, and had a daughter named Sonya who lived in Buffalo. Sang-Keun Kim, mustache, ponytail; I thought I’d seen him back in the eighties in porno movies. Frances, a granny in a white cardigan, so happy to be here. Vishnu wanted us to know that he’d taken workshops from cartoonists more famous than me. Rebecca, the skinny one, worked in Hartford as a midwife. Behind the sinks, a teenage girl wearing a wool hat, deerskin slippers, and flannel pajama pants looked up through a face screened in acne. I asked her to move closer. She said no. Her name was Rachel.

I passed around a ream of eleven by seventeen and asked everybody to take some.

I hadn’t published anything in six years. I worked as an illustrator now, at an esteemed magazine of politics and culture, a venerated institution of American journalism and the second-or third-oldest magazine in the country. Illustration is to cartooning as prison sodomy is to pansexual orgy. Not the same thing at all. Anyway, you might’ve seen my magazine work but didn’t know it—unless you happened to be scanning for names with a microscope. Some watered-down version, muted to satisfy commercial demands.

I’d been so full of promise, so amazed to have graduated from the backwater of fanzines and college newspapers to mainstream publishing. I had an appointment with destiny, I’d barely started, then I blinked and it was over. Nobody writing to beg for a blurb, no more mysterious checks arriving in the mail, no agent’s letterhead clipped to the check, no more calls from my publisher, not even to say go fuck yourself. What I missed most of all, had lost or forgotten, was the making of comics, triangulating the pain of existence through these bouts of belligerence, shame, suspicion, and euphoria, writerly noodlings and decipherable images organized into an all-encompassing environment. No more bragging, no more swagger, no more tasteless personal revelations. Cartoonists still made comics, and I hated them to the core of my filthy soul, and prayed for the return of 1996, when everything that would happen was about to happen, when I’d try to imagine how far I’d go.

If you’ve experienced precocious success, you know it’s rare. At first it seems like there must be some mistake, but you get used to it in a hurry; you’re sure it’ll always be this way. You travel, and meet famous cartoonists; they praise you, you chat like old friends and get to know them personally, you get sick of their whining and quickly lose respect for anyone on earth who struggles or complains. You come to expect fan mail, strangers popping up to kiss your ass, a certain deference or tone of voice. You start to think that anyone making comics who is without a national reputation, or miserable or obscure and lacking attention from jerkoffs in Hollywood, is a fucking moron.

I wrote on the board, Plumber, Hitler, moneybags, “Let’s just take a couple minutes here—” hayseed, hottie, hobbit,

“—to sketch these—”

lunch lady, Nabokov, beer wench, “—keep the pencil moving—” Sasquatch, sous-chef, snowman.

Then I walked around, trying not to look accusingly or even curiously at anyone, offering praise, encouraging spontaneity, saying positive stuff.

“Love it” . . . “Yes!” . . . “Lusty!” . . . “Good!”

The whole idea of this doodling was to lower the anxiety level in the room, to lighten the mood, to give them a feeling of poise and excitement, to discover in any character the autonomous core—

“Maybe another minute to wind up the one you’re on—”

—to raise the body temp and get the molecules bubbling. Then I went to the board and drew a snowman with a grin made of coal, and an indent where the nose should be, and this huge honking carrot, slightly bent, sticking out below the equator, you know where. Underneath the snowman I wrote, “Hungry?”

They laughed.

“Humor arises from the surprising juxtaposition of text and image.”

I drew a rabbit with a worried face, staring at the carrot. Then I erased the rabbit and put the carrot back where it belonged. I drew Satan in an overcoat, with a scarf around his neck, leaning on the snowman, complaining on the phone that the thermostat was broken. Then I got rid of Satan and drew a second snowman saying to the first, “Why does everything smell like carrots?”

“When you look at a comic, do you read the words first? Or look at the drawing?” We went around the room and shared our thoughts.

Then I broke them into groups, and for the next twenty minutes they made a racket, shouting, telling tales, arms flapping. They exchanged ideas, offered feedback and helpful insights, discussed, dissected, and ripped each other to shreds. In an email I’d sent out a month earlier, I’d asked them to bring along notes, a script, and some art, exhorting them to bravely mine their personal experiences for therapeutic and artistic gains, in order to come up with the one important story they’d develop this week. Rebecca had in mind a moment inside an ambulance, her younger self in a paramedic’s uniform, leaning heavily over an old man, working to restart his heart, failing to, panic setting in. Sarah wanted to do something light and fun about her job in a bookstore. Brandon, in the white polo, made notes on his first gay pride weekend, bleaching his hair, snorting amyl nitrate, realizing, in the end, If you’ve seen one drag queen, you’ve seen ten thousand. They had four days to turn their thumbnails into finished pencil drawings, which they’d then ink and letter, scan and reproduce, and present to the world by Tuesday afternoon, in time for open studio.

I asked if anyone needed help. Mel fumbled with her pencil sharpener. I heard crickets chirping in Sarah’s empty head. Then I walked to the back of the room and looked at the floor. I heard pencils and paper, the steady breathing of humans at work. I stood behind the printing press, my hands on the wheel, like a sea captain trying to get on course.

By the time we took a break, other classes had also made their way outside to the picnic tables in the courtyard. A breeze as light as champagne bubbles swept over us from the bay. Sailboats dotted its sparkling waters. I felt relieved. I’d been nervous before class, and almost puked at breakfast. That first lecture always unhinged me, but I’d gotten through it.

But there was something else not right, and it took me a second to figure out what it was: Angel Solito, walking out of Fine Arts, squinting into the sun, coming toward me. He wore a navy blue hooded sweatshirt with long white strings. His arms hung down at his sides, and he wore eyeglasses. I said something, and he reached out a hand. His face was bumpy, as if a rash was trying to come through from underneath, and his hair had been slept on or pushed up into a ridge.

I couldn’t tell if he had any clue who I was, but I knew an editor of a British anthology who knew him. I said her name, like I didn’t care either way, and sternly congratulated him on his book.

“Uh-huh.”

He was the cartoonist who Carl, the director, had hired. Solito was young enough to be my son, if I’d had a son at fourteen, and on closer inspection the whites of his eyes were laced with red threads and his head tipped forward as if he had horns. Maybe he’d been heading to the big black plastic coffee urn on the picnic table behind me and I’d gotten in his way. Maybe he didn’t care, and just needed to vent, and would’ve talked this way to anybody. He shook his head and said, “Man, it’s been crazy,” and told me how exhausted he was, how he ran out of money two days ago and was waiting for a check from his publisher. As soon as the conference ended, he’d be hitting the road again.

“The book rolls out overseas, in Sweden and Denmark—”

At some point I realized he was confiding, I was being confided in, and I guess I appreciated that.

“—then the big rollout in Europe, at the end of the summer, beginning of fall—”

Chewing his lower lip, blinking at me, talking about some French fellowship, oblivious, harassed, as if French people had been calling all night and he hated to disappoint them, as a woman appeared at his side, with flyaway hair and skin so fair she was glowing, hugging his book to her chest.

“I’m so tired, man, I haven’t done any work in, like, months—”

As another young woman walked past us in pigtails, then stopped short when she realized it was him.

“—new idea for a book but I need to get into a quiet place, and hopefully kind of erupt—”

“Sure, of course.”

“You’ve been living the life for, like, ten years!” he said, taking a step toward the picnic table and his waiting fans. “You gotta tell me what it’s like. That’s why we gotta hang out!”

“Absolutely!” Fuck you.

He gave me a tired wave, a polite smile, almost sad, and I gave him a reassuring nod.

Tell you what it’s like, Angel. I sold ten thousand books in the last six years. He sold a hundred thousand copies in hardback in three months and foreign rights in thirty-eight countries. That’s, like, a million bucks in royalties. The woman in pigtails hesitated, but the blond one had her book ready and jumped.

I’d seen his work somewhere, maybe I saw an excerpt in some anthology, or maybe his publisher sent me a galley, or I might’ve seen it in a bookstore, in a stack on a table in front, and stood over it for however many hours it took to read the thing from start to finish, before stumbling back out into daylight, shivering and mumbling to myself, groping my way out the door.

Ran out of money. That fucker!

Angel Solito traveled from Guatemala to California, mostly on foot, mostly alone, eleven years old, walked a continent to find his parents, and finally did but never found the American dream. His story was rendered in clear bold lines, with faces delicately hatched, with big heads and a ferocious expressiveness. Reviews of his work had been universally frothy. In the days after I read it I had strange moments, traveling to some breathy place, almost happy, imagining that it was my book, my story, that I’d walked three thousand miles to find my parents, four and a half feet tall, eighty pounds, and alone.

He stood by the picnic table as more bodies surrounded him. He had caramel skin and shiny black hair. I felt the thrill of being him, like they were digging me, thanking me. I’d dreamed of the big time, and here it was, so beautiful, so real! Then I remembered that I didn’t get robbed by soldiers and chased by wolves. I didn’t crawl across the Sonoran Desert. Where I came from, eleven-year-olds could barely make their own beds.

I grew up in a middle-class suburb with good public schools an hour north of the G.W. Bridge, under a stand of white pine trees in an old house with wavy wooden floors and a loose banister. Walking thousands of miles to find my family would’ve been un- necessary. My brother lived across the hall. My father sold life insurance and other tax-dodging instruments from a skyscraper in New York City. My mom taught music to fourth, fifth, and sixth graders, in an attempt to make up for her own artistic failures. We lacked for nothing in that house except talent.

Back in the studio, a dozen people sat bowed, bent over their desks—doing what? Trying to pump life into a poorly realized, made-up world. Brandon didn’t know where to put his word balloons, and Rebecca needed a beveled edge, and Sang-Keun couldn’t figure out how to draw a cowboy hat.

“It’s round but curved,” I said, leaning over his shoulder. “Like a Pringle potato chip. A disk intersecting an ovoid.”

What did he see as my hand flew across the page? Several cowboy hats, spilling out of a pencil. Did he notice how each one was unique and expressive, reflecting the life of its owner? Did he note the skill or understand how hard I worked to make some- thing difficult look effortless?

He touched the collar of his T-shirt, staring at the drawing as I moved to the next desk. He didn’t know anything. He didn’t care. I showed Sarah how to turn on the light box, and walked to the sinks and looked out the window, and tried my best to stay out of the way as a new generation of artists pounded at the gates of American graphic literature.