Excerpt

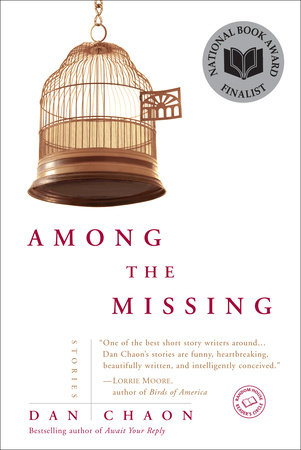

Among the Missing

Safety Man

Safety Man is all shriveled and puckered inside his zippered nylon carrying tote, and taking him out is always the hardest part. Sandi is disturbed by him for a moment, his shrunken face, and she averts her eyes as he crinkles and unfolds. She has a certain type of smile ready in case anyone should see her inserting the inflator pump into his backside; there is a flutter of protective embarrassment, and when a car goes past she hunches over Safety Man’s prone form, sheilding his not-yet-firm body from view. After a time, he begins to fill out—to look human.

Safety Man used to be a joke. When Sandi and her husband, Allen, had moved to Chicago, Sandi’s mother had sent the thing. Her mother was a woman of many exaggerated fears, and Sandi and Allen couldn’t help but laugh. They took turns reading aloud from Safety Man’s accompanying brochure: Safety Man—the perfect ladies’ companion for urban living! Designed as a visual deterrent, Safety Man is a life-size simulated male that appears one hundred eighty pounds and six feet tall, to give others the impression that you are protected while at home alone or driving in your car. Incredibly real-seeming, with positionable latex head and hands and air-brushed facial highlights, handsome Safety Man has been field-tested to keep danger at bay!

“Oh, I can’t believe she sent this,” Sandi had said. “She’s really slipping.”

Allen lifted it out of its box, holding it by the shoulders like a Christmas gift sweater. “Well,” he said. “He doesn’t have a penis, anyway. It appears that he’s just a torso.”

“Ugh!” she said, and Allen observed its wrinkled, bog man face dispassionately.

“Now, now,” Allen said. He was a tall, soft-spoken man, and was more amused by Sandi’s mother’s foibles than Sandi herself was. “You never know when he might come in handy,” and he looked at her sidelong, gently ironic. “Personally,” he said, “I feel safer already.”

And they’d laughed. Allen put his long arm around her shoulder and snickered silently, breathing against her neck while Safety Man slid to the floor like a paper doll.

Now that Allen is dead, it doesn’t seem so funny anymore. Now that she is a widow with two young daughters, Safety Man has begun to seem entirely necessary, and there are times when she is in such a hurry to get him out of his bag, to get him unfolded and blown up that her hands actually tremble. Something is happening to her.

There are fears she doesn’t talk about. There is an old lady she sees at the place where she often eats lunch. “O God, O God,” the lady will say, “O Jesus, sweet Jesus, my Lord and Savior, what have I done?” And Sandi watches as the old woman bows her head. The old woman is nicely dressed, about Sandi’s mother’s age, speaking calmly, good posture, her gloved hands clasped in front of her chef’s salad.

And there is a man who follows Sandi down the street and keeps screaming, “Kelly!” at her back. He thinks she is Kelly. “Baby,” he calls. “Do you have a heart? Kelly, I’m asking you a question! Do you have a heart?” And she doesn’t turn, she never gets a clear look at his face, though she can feel his body not far behind her.

Sandi is not as desperate as these people, but she can see how it is possible.

Since Allen died, she has been worrying about going insane. There is a history of it in her family. It happened to her uncle Sammy, a religious fanatic who’d ended his own life in the belief that Satan was planting small packets of dust in the hair behind his ears. Once, he’d told Sandi confidentially, he’d thrown a packet of dust on the floor of his living room, and suddenly the furniture began attacking him. It flew around the room, striking him glancing blows until he fled the house. “I guess I learned my lesson!” he told her. “I’ll never do that again!” A few weeks later, he put a shotgun in his mouth and pulled the trigger.

Sandi’s mother is not such an extreme case, but she, too, has become increasingly eccentric since the death of Sandi’s father. She has become a believer in various causes, and sends Sandi clippings, or calls on the phone to tell her about certain toxic chemicals in the air and water, about the apocalyptic disappearance of frogs from the hemisphere, about the overuse of anti- biotics creating a strain of super-resistant viruses, about the dangers of microwave ovens. She accosts people in waiting rooms and supermarkets, digging deep into her purse and bringing up photocopied pamphlets, which she will urge on strangers. “Read this if you don’t believe me!” And they will pretend to read it, careful and serious, because they are afraid of her and want her to leave them alone.

But she is functional. At sixty-eight, she still works as a nurse’s aide on the neurological ward of the hospital. She’ll regale Sandi with the most horrifying stories about her brain-damaged patients. Then she’ll say how much she loves her job.

Sandi, too, is functional. Besides Safety Man, there is nothing abnormal about her life. She works, like before, as a claims adjuster at the IRS. She used to have trouble getting up in the morning, but now she wakes before the alarm. She is showered and dressed before her daughters even begin to stir; she has their cereal in the bowls, ready to be doused with milk, their lunches packed, even little loving notes tucked in between bologna sandwiches and juice boxes. She stands at the door as they finish their breakfasts, sipping her coffee, her beige trench coat over her arm. At this very moment, hundreds of women in this exact coat are hurrying down Michigan Avenue. She is no different from them, despite the inflatable man in her tote bag.

The girls love Safety Man. Megan is ten and Molly is eight, and they have decided that Safety Man is handsome. They have been involved in dressing him: their father’s old black leather jacket and sunglasses, and a baseball cap, turned backward. They are pleased to be protected by a life-size simulated male guardian, and when she drops them off at school, they bid him farewell. “So long, Jules,” they call. They have decided that they would like to have a boyfriend named Jules.

Sandi works all day, picks up the girls, makes dinner, does a few loads of laundry. She doesn’t have hallucinations or strange thoughts. She doesn’t feel paranoid, exactly, though the odor of accidents, of sudden, inexplicable death is with her always. Most of the time, during the day, her fears seem ridiculous, and even somewhat clichéd. She knows she cannot predict the bad things that lie in wait for her, can never really know. She accepts this, most of the time. She tries not to think about her husband.

Still, when the girls are asleep and the house is quiet, Sandi feels certain that he will appear to her. He is here somewhere, she thinks. The most supernatural thing she can imagine is the idea that he has truly ceased to exist, that she will never see him again.

At night, she goes down to the kitchen, which is where he passed away. He had been standing at the counter, making coffee. No one else was awake, and when she found him he was sprawled on the tile, not breathing. She called 911, then pressed her mouth to his lips, thrust her palms against his chest, trying to remember high school CPR. But he had been dead for a while.

She finds herself standing there in the kitchen, waiting. She imagines that he will walk in, a translucent hologram of himself, like ghosts on TV—that loping, easygoing tall man’s walk he had, a sleepy smile on his face. But she would be satisfied even with something less than that—a blurry shape in the door frame like a smudge on a photo negative, or a bobbing light passing through the hall. Anything, anything. She can remember how badly she once wanted to believe in ghosts, how much she’d wanted, after her father died, to believe that he was watching over her—“hovering above us,” as her mother said.

But she never felt any sort of presence, then or now. There is nothing but Safety Man, sitting in the window facing the street, his positionable hands clutching a book, his positionable head bent toward it in thoughtful repose, a Milan Kundera novel that she’d found among Allen’s books, a passage he’d underlined: “Chance and chance alone has a message for us. Everything that occurs out of necessity, everything expected, repeats day in and day out, is mute. Only chance can speak to us. We read its messages much as gypsies read the images made by coffee grounds at the bottom of a cup.” Alone beside the standing lamp, Safety Man considers the passage as Sandi sleeps. Because he has no legs, his jeans hang flaccidly from his waist. He reads and reads, a lonely figure.

Most of the time, Sandi is okay. Everything feels anesthetized. The worst part is when her mother calls. Sandi’s mother still lives on the outskirts of Denver, in the small suburb where Sandi grew up; her voice on the phone is boxy and distant. Mostly, Sandi’s mother wants to talk about her job, her patients, whom Sandi has come to know like characters in a book—Brad, the comatose boy who’d been in a bicycle accident, and whose thick, beautiful hair her mother likes to comb; Adrienne, who had drug-induced brain damage, and who compulsively hides things in her bra; little old Mr. Hudgins, who suffers from confusion after a small stroke. Sometimes he feels certain that Sandi’s mother is his wife. But the cast of her mother’s stories is always changing, and Sandi has learned not to become too attached to any one of them. Once, when she asked after a patient that her mother had talked about frequently, her mother had sighed forgetfully. “Oh, didn’t I tell you?” she said. “He passed away a couple of weeks ago.”

Sometimes, Sandi’s mother likes to talk about death or other philosophical issues. One night after dinner, while Sandi is drinking tea at the kitchen table and the girls are watching music videos on television, Sandi’s mother calls to ask whether she believes in an afterlife.