Excerpt

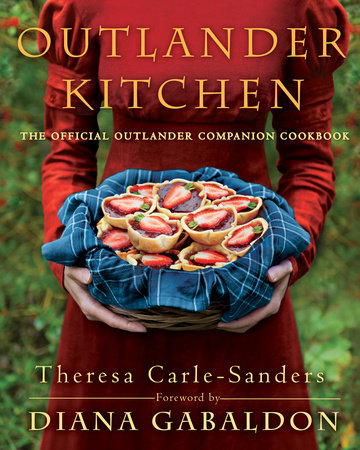

Outlander Kitchen

My Outlander Kitchen

Pantry

A time-traveling kitchen requires a versatile pantry. Many ingredients we have come to depend on in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries were not common, or even in existence, in the eighteenth. Other ingredients that were staples two hundred years ago have been lost to our industrialized food system that, in many ways, values convenience over taste and nutrition.

That said, aside from the game meats and a few spices, you won’t find a lot of exotic ingredients in Outlander Kitchen. I did most of my shopping while writing it in my small island’s (population 2,200) grocery store. For the rest, I ventured into the big city and its specialty shops and superstores. When that failed, I always found what I was looking for online, a few short days away by mail.

Remember that a recipe is a guideline, not a blueprint. Use what you have and find inspiration for substitutions in your pantry, rather than buying ingredients that you may use only once. For my part, I’ve tried to avoid pantry one-hit wonders—ingredients you buy for a single recipe and never use again. In most cases, if I call for an exotic spice or condiment, you’ll find it in at least one other recipe; for example, rosewater is used to flavor the Almond Squirts (page 272) as well as the Buttermilk Lamb Chops with Rosewater Mint Sauce (page 136).

Read the recipe through at least once before you go shopping, then again before you start cooking. Prep all of your ingredients before you begin, and I promise you will find that everything goes much more quickly and smoothly, and that cooking along with your favorite books can actually be an enjoyable way to spend a couple of hours, or even a whole afternoon.

Below are a few notes about common Outlander Kitchen pantry staples.

Butter In restaurant and industrial kitchens, where the recipes are made to serve dozens or even hundreds, the differences between salted and unsalted butter make a big difference. At home, I use salted and unsalted butter interchangeably for most things—the difference is negligible when you’re cooking for smaller numbers. Unless I specify one or the other in a recipe, use what you have on hand.

Buttermilk A frequent ingredient in the recipes that follow, and a staple in my fridge. From time to time, however, I find myself without any and have a craving for Mrs. Bug’s Buttermilk Drop Biscuits (page 246). Although not quite the real thing, either of these substitutions works in a pinch:

● Stir together 1 cup milk and 1 tablespoon lemon juice or vinegar. Let stand 15 minutes at room temperature until thickened and curdled.

● Stir together ¾ cup plain yogurt or sour cream and ¼ cup milk. Let stand 10 minutes at room temperature.

Cornstarch Primarily used as a thickener, cornstarch is known as corn flour in most places outside North America.

Cream Use whipping cream (30 to 35% fat) and heavy cream (36% and up) interchangeably in Outlander Kitchen recipes. Substitute double cream (up to 48% fat) for extra richness. The more fat cream has, the more stable its whipped peaks, and the more heat and acid it can withstand before curdling. Other recipes call for light cream, also known as “single” and “table” cream, which are all different names, depending on your geographic location, for cream that has about 18 to 20% fat.

Eggs I always use large eggs. Once separated, yolks should be used immediately, but the whites will keep in the fridge up to five days or in the freezer up to a month. Use them to bulk out a Bacon, Asparagus, and Wild Mushroom Omelette (page 45), for a sweet batch of Almond Squirts (page 272), or beat one with a drop of water and a pinch of salt to make an egg wash for pastry.

Flour All-purpose flour in North America is sold as plain flour just about everywhere else. When baking with whole wheat flour, I use stone-ground flour exclusively.

Herbs I use fresh herbs liberally, just like cooks of the past, to add flavor and aroma. Even those with black thumbs find most herbs relatively easy to grow in a variety of climates. Most of my herb garden regularly survives the relatively mild winters of the Pacific Northwest, but others in more extreme climates keep small pots of herbs on a windowsill during cold months, or buy what they need from the produce section. When fresh herbs are unavailable, substitute about half the amount of dry.

Nutmeg This much-prized seed of a tree native to the Spice Islands of Indonesia was popular for centuries as a spice, medicine, and preservative. Preground nutmeg is tasteless. Buy it whole and grate it, as needed, on a rasp.

Oatmeal Unlike in most of North America, where oatmeal refers to cooked oat porridge, in Britain, oatmeal refers to a meal, from coarse to fine, ground from hulled oats. Traditionally ground on a millstone, it is used extensively in Scottish cooking to make everything from a dense parritch to scones and haggis. I make my own oatmeal by grinding rolled oats in my food processor or coffee grinder. See Grinding Grains, Nuts, and Seeds (page 10).

Oats Advances in oat processing in the late nineteenth century resulted in the development of steel-cut oats, as well as rolled oats. I keep both types in my pantry, and while I tend to prefer steel-cut’s texture and nuttiness for my morning parritch, rolled is what I reach for when I am baking.

Oil While I use the generic term “vegetable oil” in all of my recipes, I specifically use sunflower or safflower oil for salad dressings and to pan-fry; to deep fry, I use peanut, avocado, or coconut oil. When a recipe calls for olive oil, I use extra-virgin.

Pepper Pepper was ridiculously expensive historically, and it was used sparingly, yet there were more varieties available to a cook in a wealthy eighteenth-century kitchen than most of us keep now. Expand your horizons with Jamaican or Balinese long pepper, and pick up some ground white pepper to keep cream sauces and pale dishes unmarred by black flakes.

Salt My mother calls me a snob for my shelf of salt, and she’s probably right. There is a time and place for every salt, but I use kosher salt the vast majority of the time. I prefer it for its flaky texture and lack of processing. Because its large flakes take up more space in a measuring spoon, it takes more kosher salt than regular table salt to season a dish, so if you are using table salt, use about half the amount of the kosher salt called for.

Stock Homemade stock is a relatively inexpensive source of protein, nutrition, and flavor that is undervalued and underused in many kitchens today. Most people cite time as the number one reason they avoid making it, and I can’t argue that stock does take some time. But if you are going to be around the house anyway, why not start a pot? Once it’s simmering, turn on the exhaust fan and walk away, remembering to check back every thirty minutes or so. All of that said, at the end of a long, hard day, any of the following recipes can be made with packaged stock. Look for no-salt or reduced-salt varieties, or use a very light hand with the salt during cooking.

Sugar Unless otherwise noted, any mention of sugar refers to granulated. Confectioners’, or powdered, sugar is also known as icing sugar outside the United States.

Whisky Scottish regulations require all bottles bearing the label “scotch” to contain whisky distilled in Scotland from malted barley (or, less commonly, rye or wheat), and aged in oak casks for a minimum of three years. Single malt whisky is produced entirely from barley malt in one distillery, while blended whisky generally contains whisky from many distilleries.

Whiskey American whiskey is defined under the law as that which is distilled from a fermented mash of cereal grain (barley, corn, wheat, rye, etc.) and aged, at least briefly, in new charred-oak casks. Arguably the most popular style of American whiskey is bourbon, made from a mash containing at least 51% corn.

White vermouth (dry) My shelf-stable substitute for white wine in cooking. It is handy to have on hand when you need a little wine to deglaze a pan, but don’t want to open a bottle.

Yeast I use instant yeast (also known as fast-rising, rapid-rise, quick-rise, or bread machine yeast) exclusively. It is easier to use, as it does not require proofing in water like active-dry yeast, and I find its results more consistent.