Excerpt

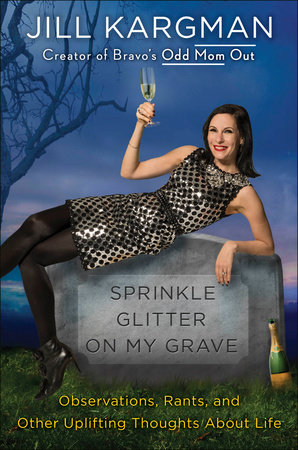

Sprinkle Glitter on My Grave

We might appear to be normal human beings, but in truth, my family is the Munsters. We used to be the Addams Family, but when my brother married a sunny Southern California bride, I now think of us as the knockoff comedic goth family, because they had that one normal blonde, too. I’m not quite sure if she was the WASPy cousin or some wholesome niece, but she didn’t seem to notice the Munsters’ creepiness at all; that is, until her suitors ran screaming from her doorstep when her frankenservant cracked the lead-studded haunted house portal.

Okay, we don’t have a doorbell that plays death knells, or a severed limb as a butler; we don’t have a butler. But we are pretty morbid and Reaper obsessed. As children, when my brother, Willie, and I argued—typical sibling disagreements—my dad would stop our nonsense short with morbidness: “Hey! When Mom and I kick the bucket, you’re gonna be all each other’s got, so knock it off!”

We were in preschool, BTdubs.

The result? Sobs. Hysterical snot-bubble bawling in our feetie pajamas. And yet he always said that every time we’d bicker.

When he went on European business trips, he usually took the Concorde—his company sprang for it when he had to go to meetings that required him to arrive looking alive. But he never liked that supersonic plane. “One of these days,” he’d say every time, “that pig’s gonna blow and I just hope I’m not on it when it does.” Tragically and memorably, he was right, that pig did blow (though without him on it).

We skied every Christmas and would be warned to be careful, because every year “Someone takes a header and rams into a tree and that’s it.”

He talked disease. Drunk driving. Choking mid-steak. We had conversations about The End all the time. He liked to discuss who was dying or who just looked like they had one foot in the grave. (“I ran into Bob today. He looks like he’s on his way out.”)

Sunday nights were our family eat-out night, usually Chinese. He’d often have just one more dumpling, because “Hey, we’re all gonna be pushin’ daisies someday.” His attitude wasn’t a cheesy you only live once–type bullshit that some people use to justify hedonistic behavior; it’s not like he encouraged me to go get high on Venice Beach or told my brother to roll a condom on that dick before it’s dust. His attitude was actually joyful. He was and is a firm believer in making the most of our time here, being productive, having strong human connections, and enjoying every day—not as our last per se, but because our days will one day run out.

His zest for life rubbed off. Rather than make us neurotics who were scared of life, all this talk and acknowledgment of death made my brother and me embrace every morsel of life. Morbidity doesn’t have to be fear inducing—au contraire, it made us drink life to the lees (after we turned twenty-one, of course) and relish every bite of food. We cherished music. We flipped on the lights and immediately flipped on the radio. We sucked the marrow out of anything that appealed to the desperate-for-fuel senses and always tried to savor memories of all that is fleeting and ephemeral.

As adults, we still have this zest for life and the same dark humor. Willie has a tattoo up both his arms in a beautiful black script: Mors certa, non vita, Latin for “Death is certain, life is not.” Now we both have kids of our own—nuggetini, we like to say—and we’re both still trying to filch as much joy as we can out of our lives, and now, our children’s fleeting childhoods. And maybe we’re passing on the tradition.

My kids aren’t afraid of spooky things because they’ve been exposed to them their whole little lives. I have art with skulls and hourglasses all around our house, and my kids don’t blink.

But one time, a little pal of my daughter Sadie’s was sleeping over and woke up in the middle of the night after a nightmare. With tears streaming down her face, she pitter-pattered into our room and burrowed into bed with me and my sleeping husband. “Mrs. Kargman, I’m scared of your house, there are so many skeledins,” she said. I cuddled her and told her they don’t have to be scary if you think of them as just part of us. I took her on a tour of the house and we greeted every skeleton, giving them each a silly name. Then I tucked her in with us, so she wouldn’t be lonely beside my comatose daughters, and she fell asleep feeling better. Harry, my husband, was a little shocked when he woke up with a kid in our bed who was not our own. Actually that’s putting it mildly. I think he said, Um, what the fuck is this kid doing in our bed? But when I explained it to him, he understood; he was once new to my family, too, and he found my Morticia side odd then, but now he totally gets it. My awesome little collection of hourglasses used to freak him out—they reminded him that time was constantly ebbing away—but now he understands the way I see that fragile shelf grouping: Time passing is constant, so don’t sweat the small shit, don’t wish away periods of time, enjoy it all. And we pretty much do.

Just as my parents have done for as long as I can remember, I reach first for the obituary section in The New York Times. And I’m not only interested in the cadavers who got headlines, I’m into the microscopic listy bodies, too. No matter the length or size of the font, I love stories of a life well lived and get inspired by what people made of their time on earth. Building on Billy Crystal’s idea in When Harry Met Sally . . . to combine the obits with the real estate section: “He leaves two sons, seven grandchildren, and a sprawling prewar penthouse with wraparound terrace.” Now that real estate has gone online, I think that’s a very good editorial suggestion, too.

A few years ago, my parents bought cemetery plots for the family and announced with pride that we’d have a plum ocean view. Since then, they’ve logged many hours looking at tombstones on Pinterest. They scrutinized fonts and interviewed a few carvers before settling on the artisan who would create what will essentially be their business card for eternity. It was around that time that Harry and I realized it was time to begin in earnest a discussion about burial with our kids, Sadie, Ivy, and Fletch. After explaining to her what a burial plot is and what a headstone commemorates, Ivy, who was four at the time, said, “Mommy, when you die, I’m going to sprinkle glitter on your grave.” I was shocked by this pronouncement. Had this kid been thinking of this for some time or had it just occurred to her? I asked her why this would be her plan. “Because,” she replied, “you are sparkly and fabulous like glitter. Plus, glitter is very hard to clean up, so it will always be there.”

Do I need to itemize the many reasons why I love this response? I don’t think so. If you’re a parent you get it—what an amazing sentiment and from such a happily morbid little person. Please consider this page part of my last will and testament. I can’t think of a more badass or groovy plan for commemorating my crossing the river Styx than Ivy’s amazing plan.

Incidentally, said plots are on Nantucket island, off the coast of Massachusetts. Neighboring island Martha’s Vineyard happens to be the resting place for the genius comedian John Belushi. His tombstone is marked with hundreds of candy wrappers his fans continue to leave for him. I remember visiting as a child and thought it was cool and hilarious because I worshipped him, but actually, now that I think of it, it’s cool but . . . kind of litter. And I prefer glitter.