Excerpt

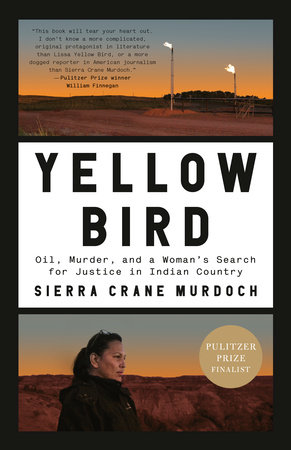

Yellow Bird

1

The Brightest Yellow Bird

Lissa Yellow Bird cannot explain why she went looking for Kristopher Clarke. The first time I asked her the question, she paused as if I had caught her by surprise, and then she said, “I guess I never really thought about it before.” For someone so insatiably curious about the world, she is remarkably uncurious about herself. She is less interested in why she has done something than in the fact of having done it. Once, she asked me in reply if the answer even mattered. People tended to wonder all kinds of things about her: Why did she have five children with five different men? Why had she become an addict and then a drug dealer when she was capable of anything else?

Lissa stands five feet and four inches tall, moonfaced and strong-shouldered, a belly protruding over hard, slender legs. Her teeth are white and perfectly straight. Her hair is lush and dark. She has a long nose, full lips, and brows that arch like crescents above her eyes. When I met Lissa, she was forty-six years old and looked about her age—though, given the manner in which she lives, one might expect her to look older. She has a habit of going days without sleep, of sleeping upright in chairs. She rarely cooks, subsisting largely on avocados, tuna, croissants, mangoes, and candied nuts, and smokes like a fish takes water into its gills. She often loses things, particularly her lighters. One night, I watched as Lissa searched for one, nearly gutting her kitchen, until she gave up, bent over the countertop, and lit her cigarette with the toaster.

She is a member of the Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara Nation, an assembly of “Three Affiliated Tribes” who once farmed the bottomlands of the Missouri River and now call a patch of upland prairie in western North Dakota their home. The Fort Berthold Indian Reservation is three times the area of Los Angeles. The tribe has more than sixteen thousand members. Like a majority of these members, Lissa has not lived on Fort Berthold in some time, but she keeps in her possession an official document establishing her tribal citizenship:

Arikara Blood Quantum: 23/64

Mandan Blood Quantum: 1/4

Hidatsa Blood Quantum: 3/16

Sioux (Standing Rock) Blood Quantum: 1/8

Total Quantum This Tribe: 51/64

Total Quantum All Tribes: 59/64

“What’s the other 5/64ths?” I once asked.

“I don’t know,” Lissa replied, “but somebody f***ed up.”

It was a joke. As far as she knew, at least two fathers of her children were white, and if anyone had f***ed up her blood quantum, Lissa thought, it was the United States government. The fractions were controversial and arbitrary, assigned to her great-grandparents in the 1930s by the Bureau of Indian Affairs to determine how many individuals belonged to the tribe and how much federal assistance the tribe thus deserved. One could be a whole Indian, a fraction of an Indian, or no Indian. The idea was that a person’s Indian-ness could be defined solely by race. It was the Bureau’s way of applying order to the mess it had made, though to Lissa the fractions had always seemed superficial. In reality, she believed, there was no clear order to her life. She had worked as a prison guard, bartender, stripper, sex worker, advocate in tribal court, carpenter, bondsman, laundry attendant, and welder. She studied corrections and law enforcement at the University of North Dakota, where she graduated from the criminal justice program, though rather than working for the police, she spent much of her adult life evading them. She was arrested six times, charged twice for possessing meth “with intent to deliver,” and given two concurrent prison sentences—ten and five years—two years of which she served. When Kristopher Clarke went missing in 2012, Lissa was on parole. Her interest in his disappearance may have seemed misplaced were it not for the fact that it made as much sense as every other random interest she had taken in her lifetime.

Lissa was born on June 13, 1968, to Irene Yellow Bird and Leroy Chase, both members of the MHA Nation. Leroy had joined the Air Force and was not present for her birth, nor was he present for the rest of her life except on a rare phone call. Irene’s mother, Madeleine, was Catholic and, since Irene was twenty-one and unmarried, arranged for a relative to take Lissa. The arrangement lasted seven months before Irene, swayed by the new radicalism of the era, decided she would not be shamed into giving up her daughter and asked for Lissa back.

It was her mother whom Lissa would later blame for the patternlessness of her life—her mother’s ambition, to be exact. After they reunited, Irene dedicated herself to academic pursuits. They left North Dakota for California, where Irene enrolled again in school, then returned to North Dakota, then left for Wisconsin, where Irene pursued another degree before returning, again, to North Dakota, where she served for a while as the only Native American professor in the state. The longest Lissa and her mother remained anywhere was three years, when they lived in Bismarck, a few hours south of the reservation. They moved to the city in 1972, when Lissa was four years old, into an apartment with a single bedroom where Lissa kept a pet fish. One day, the fish died, and Irene flushed it down the toilet. Lissa could not forgive her mother for this. It seemed unfair to her that something living, which she had loved, should end up in the sewer. Her sensitivity exasperated Irene, who supposed her daughter had wanted a full burial, with a procession and drums and star quilts draped over a casket. She supposed her daughter even wanted a priest. Lissa had acquired certain habits in church, such as fashioning bowls out of paper and placing them around the apartment. “Alms for the poor!” she called when anyone came to visit. Sometimes the visitors were her mother’s white, wealthier friends, but often they were family. “Alms for the poor!” she called nonetheless, shaking her bowls piously, until one day her mother had enough and scolded, “Lissa, we are the poor.”

Lissa had always been like this, Irene later told me—a fanatic with a bleeding heart, giving weight to weightless things. I supposed it was a kind way of explaining her daughter’s passionate tendencies, since Shauna, Lissa’s own daughter, explained them to me differently. “My mom is an addict,” Shauna said. She meant this in the broadest sense.

Shauna is the oldest of her mother’s five children, only nineteen years younger than Lissa, a generational closeness that pressed her up against her mother’s faults and made her feel them more acutely than her siblings. When Lissa started smoking crack, Shauna was eight years old. Six years later, Lissa turned to meth. But even in the years before she got high, Lissa, Shauna believed, had been prone to obsession.

Among the first of these obsessions Shauna recalled were plants. When she was in preschool, her mother had discovered an interest in growing things, and after that they kept all kinds of plants—leafy, tropical, sun-starved plants spilling from the windows of their apartment in Grand Forks, where Lissa attended college, as well as trays of vegetable starts Lissa grew from seed, though they never had any space for a garden. After that, her mother’s obsessions came in all forms, sudden and indiscriminate, but each one Lissa had taken on with the faith and focus of a zealot. For a while, it had been music—Lissa taught herself to play piano—before she purchased a camera and became an ardent documentarian.

If these obsessions sounded like hobbies, Shauna insisted they were not. It had never been enough for her mother to take an interest in something. Rather, Lissa was set on being the best at everything she did. The best drug dealer. The most dogged bondswoman. The eventual leader of each organization she joined. After Lissa emerged from prison sober, she still found plenty of things to obsess about and, in fact, it seemed that sobriety intensified her fixations. According to Shauna, the only difference between the things that occupied her mother when she was sober and the things that made her high was that Lissa often abandoned the sober things with the same swiftness and ease with which they came to her. In one of their many moves, they had left the plants behind. This was one thing Shauna expected as a child, that whatever life they were living at one moment would last only so long. Always they had kept moving, from hotels to shelters, from apartments they rented to the houses of friends, and from the papery walls of all the places they lived, her mother had hatched, again and again, changed and yet the same.

And so when Lissa first told Shauna about the oil worker who was missing—and how she planned on finding him—Shauna assumed this obsession would also pass. She thought it would last weeks or months until the young man was found. She did not think it would go on for years. “I don’t know what it was about that boy,” Shauna would say, but Kristopher Clarke was different.