Excerpt

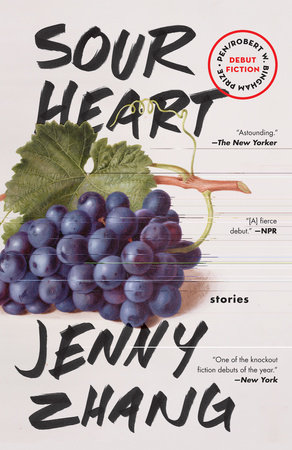

Sour Heart

We Love You Crispina

Back when my parents and I lived in Bushwick in a building sandwiched between a drug house and another drug house, the only difference being that the dealers in the one drug house were also the users and so more unpredictable, and in the other the dealers were never the users and so more shrewd--back in those days, we lived in a one-bedroom apartment so subpar that we woke up with flattened cockroaches in our bedsheets, sometimes three or four stuck on our elbows, and once I found fourteen of them pressed to my calves, and there was no beauty in shaking them off, though we strove for grace, swinging our arms in the air as if we were ballerinas. Back then, if one of us had to take a big dump, we would try to hold it in and run across the street to the bathroom in the Amoco station, which was often slippery from the neighborhood hoodlums who used it and sprayed their pee everywhere, and if more than one of us felt the stirrings of a major shit declaring its intention to see the world beyond our buttholes, then we were in trouble because it meant someone had to use our perpetually clogged toilet, which wasn’t capable of handling anything more than mice pellets, and we would have to dip into our supply of old toothbrushes and chopsticks to mash our king-sized shits into smaller pieces since we were too poor and too irresponsible back then to afford even a toilet plunger and though my mom and dad had put it on their list of “things we need to buy immediately or else we’ve just lost all human dignity,” somehow at the end of every month we’d be a hundred dollars short and couldn’t pay the gas bill in full, or we’d owe twenty dollars to a friend here and ten to a friend there and so on, until it all got so messy that I felt there was no way to really account for our woes, though secretly I blamed myself for instigating all our downward spirals, like the time I asked my father if he would buy me an ice-cream cone with sprinkles, which made him realize I had been waiting all month to ask and he felt so sorry for me that he decided to buy me not only an ice cream with sprinkles but a real rhinestone anklet that sure as hell was not on the list of “things we need to buy immediately or else we’ve just lost all human dignity,” and that was the sort of rhythm my family fell into--disastrous and depressing in our inability to get ahead--and that was why we were never able to afford a toilet plunger and why our butts were punished so severely in those years when it wasn’t as simple as, Hey, I’m going to take a crap now, see you in thirty seconds, it was more like, I’m going to take a crap now, where’s my coat and my shoes and also that shorter scarf that won’t dangle its way into the toilet and where’s the extra toilet paper in case the Indian guy forgot to stock the bathroom again (he always forgot), and later, when we finally moved, when we finally got the hell out of there, it still wasn’t simple either, but at least we could take shits at our own convenience, and that was nothing to forget about or diminish.

Before Bushwick, we lived in East Flatbush (my parents and I called it E Flat because we loved the sound of E Flat on the piano and we liked recasting our world in a more beautiful, melodious light) for a year and a half on a short little street with lots of stoops that needed fixing. We knew everyone on our street, not by name or by way of actually talking to them, but we knew their faces and we knew to nod and mouth, “hi, hi, hi,” or sometimes just “hi, hi,” or “hi!” but always something.

Our neighbors were island people from Martinique and Trinidad and Tobago. A couple of them confronted my father one evening to set the record straight that they weren’t Dominicans. We’re West Indians, they said. Tell your kids that. My father came home confused by the entire interaction, but later my mom and I figured they must have been referring to those asshole Korean kids who lived a little ways down from us and hung around outside their apartments wearing baseball caps with the bill unbent and pants that sagged around their knees, calling out whatever pitiful insults they could think of. Once, when I was walking home from the bus stop, they yelled, “Yo, it’s the rape of Nanking! It’s really the rape of Nanking!” as if yelling out the name of a terrible war crime had the ability to scare me when I was nine and had been loved my entire life by parents who vowed daily to spend their whole lives protecting me, and though in 1992 it was true that I was a small, unexceptional thing, one thing I never was was scared. Those Korean kids were goons who were going to end up dead or incarcerated or dead one day, and my parents and I loathed them and loathed being confused or associated with them just because to everyone else in our neighborhood, we were the same.

The Martinicans and the Trinidadians were the kind of people who acted like their homeland would always form a small, missing, and necessary bone in their bodies that caused them ghostly aches for as long as they were alive and away from home, and it bothered me how they clung to their pasts and acted like bygone times were better than what was happening in the here and now. They were always having cookouts in the summer and dressing in bright colors as if our streets were lined with coconut-bearing palm trees and not trash and cigarette butts and spilled food. Eventually though, I came to admire them greatly, especially the women because they had such enviable asses, which caused their belts to dip into a stretched-out V right at the spot where their cheeks met, and I used to follow that V with my eyes and so did the men, who apparently never got bored of seeing it either.

My mom had no such ass, but commanded attention anyway. The men on our block liked to stare at my mom whenever she walked past--fixed, long, concentrated gazes. Maybe it was because her hair was so straight and long and fell down her back like heavy curtains and she had skin so white that it reminded me of vanilla ice cream. That was why I drew little cones all over her arms, which she let me do because my mom let me do anything as long as it made me happy.

“What makes you happy makes Mommy happy,” she would always say to me, sometimes in Chinese, which I wasn’t so good at, but I tried for her and for my father, and when I couldn’t, I would answer them in English, which I also wasn’t so good at, but it was understood that while I could still improve in either language, my parents could not, they were on a road to nowhere, the wall was right up against them, so it was up to me to get really good, it was up to me to shine and that scared me because I wanted to stay behind with them, I didn’t want to go any further than they could go.

Sometimes, I would forget what I was supposed to say after she said something like that and I would say the wrong thing, like, “And what makes me happy is eating ice cream. Mrs. Lancaster can go suck it. Who cares if I don’t show the work? I still got all the right answers. She’s a tool, Mom.”

“Sour girl,” my mom said. “If your teacher asks you to show work, then show the work. Can’t you speak anymore without using ugly words? And I take it that what makes your mommy happy doesn’t make you happy? Am I right, sours?”

“No,” I said. “I’m sorry, I meant what makes you happy makes me happy too. I just forgot to say it.” It embarrassed me whenever my mom or my dad trumped me (although it was never on purpose) with how thoughtful they were, and by comparison, how thoughtless and selfish I had been in only thinking of myself when it seemed like every second of every day my parents were planning to undergo yet another sacrifice to make our lives that much better, and no matter how diligently I tried to keep up, there was always so much that was indiscernible. It was so hard to keep track of every detail, like how my parents shared the same pair of dress shoes, alternating their schedules so my father could wear them during the day and my mother at night even though they were four sizes too big for her and that was why she tripped so often and had so many scrapes on her body.

There were so many days when I came home to an empty house with nothing at all to distract me except an oozy desire to come up with all the ways I could possibly sacrifice enough to catch up to my parents, who were always sacrificing. But I didn’t know how I could compete with my mom, who got fired from her job baking donuts after spending a night scavenging for a desk so that I wouldn’t have to do my homework on the floor or the bed or standing up with my workbook pressed against the wall, and how she found me a beautiful desk that was perfect except someone had sprayed fuck ya momma on the side of the desk, and how she dragged it down twenty-something blocks on her own and was too exhausted to wake up in time for work, and that was why she was fired and why she couldn’t ever keep a job because she was so tired all the time from taking care of me.