Excerpt

The Mastermind

PROLOGUE

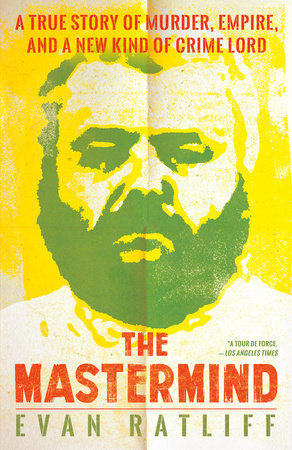

Monrovia, Liberia September 26, 2012 “I can see why you picked this place,” says Paul Le Roux, as he shifted his significant bulk deeper into a leather couch, pressed against the wall of a modest Liberian hotel room. “Because it’s chaotic, it should be easy to move in and out, from what I’ve seen.” The man’s cadence carries a twinge of Southern Africa, Afrikaans mixed with the sound of his native Zimbabwe, flattened out after years of living overseas. His large white head is shaved close, and what hair remains has gone gray as he approaches 40. He has the look of a beach vacationer cleaned up for a dinner out, with an oversized blue polo shirt and a pair of long khaki cargo shorts. His outfit is out of keeping with the discussion he is about to conduct, with a man he believes to be the head of a Colombian drug cartel, and whom he refers to only as Pepe.

“Very easy,” replies Pepe. In a video recording of the meeting, Pepe is seated just off screen, on a matching couch. His disembodied voice speaks in flawless, if heavily accented, English.

“Very few people, not too many eyes. It looks like the right place.”

“Trust me—what’s your name again?”

“Paul.”

“Paul, trust me, it’s the right place. I’ve been here already for quite a bit of time. And always, me and my organization, we pick places like this. First of all, for corruption. You can buy anything you want here. Anything. You just tell me what you need.”

“Yeah, it’s safe here,” Le Roux says, knowingly. “If there’s a problem here you can fix it. I understand this type of place.”

“Everything is easy here. Just hand to hand, boom boom boom you can see,” Pepe says, laughing. “Well, thanks to your guy here, now we are meeting.” He gestures at a third man in the room, an employee of Le Roux’s who goes by the name Jack Anderson. It was Jack who had made the initial connection between Le Roux and Pepe.

The deal Jack has brokered was complex enough that, when I meet him years later, I need him to walk me through it several times. The Colombians, who dealt primarily in the cocaine produced in their own country, were looking to expand into methamphetamine, which they wanted to manufacture in Liberia and distribute to the U.S. in Europe. Le Roux, the head of his own international organization based in the Philippines and Brazil, would provide the necessarily materials to build the Colombians’ meth labs: precursor chemicals, formulas to cook them into meth, and a “clean room” in which to synthesize it all. And while they got up and running, he could give Pepe the meth itself—he’d already stockpiled a ton of his own—in exchange for an equivalent amount of cocaine at market rates.

After months of back and forth, Jack had urged Le Roux to travel to Liberia and meet his new associate “boss to boss” to finalize the deal. Over the half-hour recording of the meeting, Jack’s face never appears.

“So where do you want to start?” Pepe says. “First of all, is the clean room.”

“It’s already shipped,” says Le Roux. “We already sent it to you this week. I will get the bill of lading and I will give it to my man here to give to your guys.”

“Ok. So it’s on the boat now.”

“It’s on the boat, it’s on the water. Also you have the designs we sent to you. If you have any problem assembling it, I’ll send guys here to assemble it like that.” He snaps his fingers.

“We shouldn’t have any. I got my guys here, my chemist. It’s going to work.”

“To compensate you for the delays, we will just, when we do business, we will give you back the money.”

“Paul, you don’t have to compensate me for nothing.”

Le Roux flicks his hand in the air. “We feel bad it took so long.”

“This is just business,” Pepe says. “We don’t have to compensate, just doing business. This is about money.”

Pepe walks through his cartel’s plans for building up his operation in Liberia. He is ready to arrange a trade of his high-quality cocaine for Le Roux’s finished methamphetamine, a sample of which Le Roux has shipped to him from his base in the Philippines. “Let me ask you a question,” Pepe says.

“Sure.”

“You are not Filipino, why the Philippines?”

“Same reason you are in Liberia. Basically, as far as Asia goes, it’s the best shit hole we can find, which gives us the ability to ship anywhere. It’s a good position. For example we can ship to Hong Kong, we can ship to Japan, we can ship to Australia from there. And the prices are very good. I mean, for the product that you are manufacturing, in Australia it’s around 150,000 dollars a kilo. If we move the other one, the one you want, to Japan, it’s around 100,000 a kilo. It’s the best position in Asia. And it’s also a poor place. Not as bad as here, but we can still solve problems.”

“You are cooking your shit in the Philippines?,” Pepe says.

“Actually right now we manufacture in the Philippines and we also buy from the Chinese. We’re getting it from North Korea. So the quality you saw was very high.”

“That’s not just very high. That is awesome.”

“Yeah.”

“I was going to tell you that later on, but now that you talk about it: That stuff is fucking incredible.”

“That is manufactured by the North Koreans,” Le Roux says. “We get it from the Chinese, who get it from the North Koreans.”

“So my product is going to be the same, the amount that I’m going to buy from you?”

“The same. Exactly the same.” Le Roux nods. “I know you want the high quality for your market.”

“Yeah because the product—you know that one of the best customers and you probably know that, is the Americans.”

“Number one.”

“It’s the number one. They are fucking—they want everything over there. I don’t know what the word is from Spanish. Consumistas? Consumists?”

“Consumers,” Jack interjects, off camera.

“Yeah they buy everything and they never stop,” Le Roux says.

“So everything that I ship is to America,” Pepe says. “Trust me, when I brought this, fucking everyone was asking me for it. Everyone.”

“That stuff comes from the North Korean government, that’s why it’s so good,” Le Roux says. “They don’t care, they have a building like this size just to make this stuff.”

Le Roux and Pepe consider different payment possibilities. First they will trade the cocaine for meth. After that, Le Roux says that he will be happy to be paid in gold or diamonds. If they need to conduct bank transfers, he works primarily through China and Hong Kong, although he sounds a note of caution. “We just had, in Hong Kong, 20 million dollars frozen. By bullshit. They don’t need any excuse. Just be careful. It still works, but you need to be cautious. It becomes worse, because the American, he likes to control everything. And they are there, making a lot of trouble.”

“I say fuck Americans,” Pepe says. “Americans, like you say, they think that they can control everything, but they cannot. It’s not impossible, but they cannot. We have to be very careful.”

They discuss shipment methods, and how many kilos of each drug the other could move in a month. Le Roux owns ships picking up loads in South America and traveling to Asia, but he much prefers to work in Africa, territory he knows well. His customers are in Australia, Thailand, China. “We are not touching the U.S. right now,” he says.

“Why not?”

“Actually we move pills in the U.S..”

“What kind of pills?”

“Oxycodone, hydrocodone, tramadol, phentermine,” Le Roux says. “These American fucks, they have an appetite for everything. They are like whores. They will just spend and spend and spend, they don’t give a shit. They buy everything.” Indeed, Paul Calder Le Roux has gotten rich, fabulously rich, by selling tens of millions of pills to Americans over the internet, for nearly a decade. But unlike Pepe’s organization, Le Roux avoids shipping street drugs like meth to the States. “It generates too much heat,” he says.