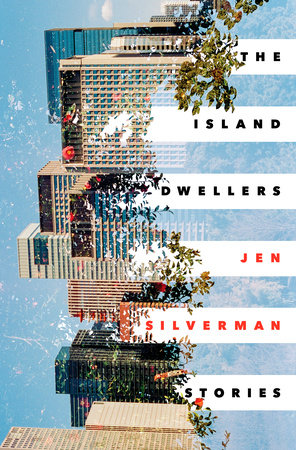

Excerpt

The Island Dwellers

Chapter 1

Girl Canadian Shipwreck

When I was younger and I heard about anybody trapped anywhere, my first response was always just: why don’t you leave?

Trapped in a job? Leave.

Trapped in a place? Leave.

Trapped in your car under a river? Crank the window open and swim to freedom.

It was a great and simple solution that I alone had come up with, and I didn’t understand why nobody else had managed to grasp the concept. Among my friends, I was the Messiah of this movement. I said things like: “If that apartment sucks, just move.” And: “If you need to fuck a lot of people, just leave him.” And: “Study abroad!” My friends said things like: Oh and Wow and Hmm and It’s Not That Simple, and You Make It Sound So Simple.

When I grew older, however, it wasn’t so much that I learned that I was wrong (this is still a philosophy that, intellectually, I subscribe to), but rather that there were scenarios I hadn’t thought of. For example: imagine an island. You are on this island. You are alone. There is nobody else with you. Leave! you might say. Okay. But you need a boat. There is no boat on your island, so you need to build a boat. Build a boat! you might say. Okay, but you don’t know how, and there is no Wi-Fi on your island, so you can’t look it up on YouTube—but okay, you can guess how to build a boat. It involves chopping down trees and hewing them and fastening them and—fuck it, you’ll build a raft. But you need tools. You need sharp tools that will chop through wood. You have no tools. And you’re so tired. This entire attempt has made you tired. So what are you going to do? Well, you don’t know, and you haven’t given up on the idea of leaving, but you’re just going to sit very still for a time. You’re just going to sit very still and not move at all, and try to filter the right answer out of the shadow that is descending from the canopy of uncuttable trees that loom over your head.

You see, there is a scenario in which you can’t just Leave.

Now imagine that there are a hundred of these islands. And on each island is a little person, crouched down on the ground, trying to filter sense out of shadow, without a boat. Now you have a hundred people who can’t just Leave.

And so it goes.

Sometime in June, I go see Camilo perform. We’ve been dating for two years, and as Camilo’s girlfriend, it’s my duty to attend his first performance piece in all that time. He’s so excited that I can’t tell him my deep personal failing: namely, that I don’t like performance art. I think either you’re performing, or you’re making art. I think that performance art is something that people do because they’re not good enough actors to just perform, and they’re not skilled enough artists to just make art.

But I don’t say this.

On my way to the venue, a basement in deepest Brooklyn, I talk out loud to myself. I practice telling Camilo that I love his work, without sounding like I’m lying. It’s harder than you think, but I find that it relies more on tone of voice than words, and by the time I get there, I sound convincing.

Camilo’s friends Ev and Keira meet me on the sidewalk outside. Ev has been a lesbian, but Ev is about to transition into being a man. Ev’s current gender pronoun of choice is E. Ev says that certain things are inherent, that E identifies as gay before E is a gender, and therefore when E fully becomes a man, E will have no choice but to date men. I understand the idea of inherence. As in: this person is inherently skilled. This person is inherently clumsy. I am concerned because Camilo is inherently clumsy with things like words and money and other people’s feelings. He loses his socks and he interrupts you. If you are inherently clumsy, chances are slim that you will make finely tuned work.

We crowd into the basement. Keira keeps her sunglasses on. Keira is only here for Camilo, she wants that to be clear. Keira is the friend you talk to when things go wrong in your life, because things are constantly wrong in hers. She is very good at telling you it is not your fault, when quite possibly it is your fault. This is a good friend for you to have, but not a good friend for your girlfriend, because you will only ever mention her to Keira when you are angry and sad.

Sometimes I make Camilo sad, and this is the first thing Keira knows about me. She knows that I once said that I didn’t understand how Camilo’s friends could protest the death penalty and then walk by homeless people on the street—if you believe all human life has value (which I do not), then shouldn’t you act accordingly at all times? Camilo wouldn’t speak to me for a day after that, nor would he articulate which part of my statement upset him the most.

What Keira does not know about: The time Camilo and I skipped work, took the Metro-North outside the city to Dia: Beacon, and ate picnic sandwiches in the grass. The time we read the entirety of Roald Dahl’s The Twits out loud on the subway, during a trip from the top of Manhattan to the tail of Brooklyn. The time Camilo had a brief but intense nervous breakdown, after a prolonged phone call with his mother, and I stayed up the whole night talking him through it.

These are not the things you would ever tell a friend like Keira, even if they are also part of the map of your relationship. Keira has one map, and the friend to whom you tell all your good things has the other map, and you just have a jumble of chicken-scrawl on a napkin. And that is why your friends always think they know where you should be going, and yet you yourself are so often lost.

For the past two years, I have been dating Camilo, and not leaving. I moved to the large brownstone co-op in which he lives, where things like books and plants and people go missing, slide between the cracks of the ancient and splintering floorboards. There are whole countries that have gone missing inside this house. There are people who emerge from doorways and their faces are unrecognizable faces, because they are faces that have gone missing as well. In this way, Camilo and his house together are not unlike the island of Doctor Moreau.

Now we’re in the basement. We are invited to line the walls, standing or kneeling, creating an open rectangle in the center. There is a microphone, waiting at the end of the open rectangle. The concrete floor is cool under my knees, and it feels good after the humidity outside. As the last people trail inside and settle into a hush, Camilo walks out. We are silent, eyes trained on him. He is wearing a white T-shirt. The armpits are stained. The elastic of his black sweatpants is too old, they’re sagging dangerously at the waist, and his long hair is loose. I can’t tell if he looks like an Artist or a serial killer. I hope everybody in the room is thinking he looks like an Artist. I hope they’re thinking about how authentic he seems, how unfettered by societal norms. I briefly hate myself for even letting the thought serial killer slip across my mind. Ev, Keira, and I arrange our faces to look encouraging. Keira makes a little “yeah” noise, a little “go get ’em tiger” noise, but Ev is completely focused. Ev also identifies as a performance artist, and is Taking This Seriously. Regardless of why we’re here, we all want him to succeed. We desperately want this to be good. The better it is, the less lying we will have to do.

Camilo starts to windmill his arms. I think he’s stretching, he’s working up to something, he’s preparing for takeoff. He keeps windmilling. Any minute now, he’s going to stop, shake himself off, and begin something that requires very loose shoulders. He keeps windmilling. Now two minutes have passed and Camilo is still very vigorously windmilling his arms. I sneak a sideways look at Keira. Her sunglasses are still on and you can’t see her eyes and suddenly I’m jealous that I didn’t think of wearing sunglasses. Now it’s three minutes. I am starting to be concerned for Camilo’s rotator cuffs. My best friend is in med school, and she has told me about rotator cuff injuries and how often they require surgery. She has told me that you may think cartilage is tough, but actually in certain situations it tears like paper, and then you’re fucked. Camilo’s cartilage might be tearing this very second, and for what? Now it’s four minutes. Keira’s sunglasses reflect a small and determined Camilo, glistening with sweat, churning his arms in circles.

Ev gets up. For one shocked moment, I think E is going to leave. E has decided that This Is Not Art, and is going to leave! Is this a gesture of great friendship, because of the depth of its honesty? Should I, as his girlfriend, be so honest as well? The idea is wild and liberating. Then Ev walks to the microphone stand, and I realize that Ev and Camilo must have agreed to this ahead of time. There is a piece of paper taped to the stand. E lifts it up. E begins to read.

As Camilo windmills his way up and down the room, Ev reads a series of sentences about Camilo’s mother. These are recollections from when Camilo was a child. His mother is cool and brutal and absent. The sentences all seem to begin “I am six (or eight or four or ten), and my mother . . .” and then they finish badly. She frightens him. She chastises him. She abandons him, for days or weeks at a time. Ev’s voice seems to incite Camilo to a more vigorous windmilling. Ev stops mid-sentence, replaces the paper, and walks offstage. A moment. We are hushed. Is it over?

But no. Keira jumps to her feet. Now she understands what is being asked of her, of all of us, as audience members and participants. She darts into the open space and picks up the piece of paper, with great purpose. She reads from the paper in a big voice. Camilo’s mother once locked him in a closet. Camilo’s mother threw away his diary. Camilo’s mother hangs up the phone before he is finished talking.

Some are stories that I knew already, but I thought they were private quiet stories told late at night, and now they are stories being told in big voices in a big basement with mid-afternoon light soaking through the street-level windows. This changes the stories. I don’t want it to change the stories, but it changes the stories.

Keira stops mid-sentence, the way Ev did, and returns to the wall. We wait through a long painful silence. The look on Camilo’s face is a frown bordering on ecstasy. He’s a little biplane, propelling itself forward and backward. His shirt has ridden up now, his sweatpants have slid down. The crisp curl of his stomach hair is visible, and the partial curve of an ass-cheek. Art is messy, I think defensively, in case anyone in the crowd is thinking that he looks insane. Art is not put-together.

A man that I don’t know goes up to the microphone stand. He takes the paper hesitantly. He is older than we are. I don’t know if he wandered in here by accident. I like to imagine that maybe he did. Maybe he is a Brooklyn Dad, and he was Wandering By, and he noticed the crowd through one of the street-level windows, and he wanted to see What the Kids Were Doing. He has a decent face. He reads some sentences, but now they have looped back on themselves, they are repeating. Camilo makes the same gestures and the man reads out loud the same stories that Camilo told me late at night, that are the same sentences that Ev and Keira just read out into this dog-damp basement, that are the same sentences anyone will read for however much longer this performance lasts—and I have a moment of pure and unflinching comprehension:

This is Hell.

I never thought there was such a thing as Hell, but this is it.

Here I am, Trapped in Hell.

I have been a bad human.

I have been a bad girlfriend.

I have lied and said I didn’t get texts that I actually got but didn’t want to reply to.

I have lied and said I had plans, when I just wanted to be alone.

I have lied and said “Yes that was good” after we had sex and it was bad and he asked if it was good.

I have lied and said that it’s okay that he’s stopped using shampoo because he doesn’t believe in shampoo anymore, but actually I don’t think it’s okay, I think people should wash their hair.

I am a judgmental person, a cynic, a capitalist, someone who does not share with Camilo and his friends their fervent, delirious belief in the life-changing potential of political protest and art.

I am a sad lonely person with conservative values and a crippled soul who cannot appreciate performance art.

And this is my punishment. Here, in Hell.

And, what’s more, I know what Dante once knew: Hell consists of many rings. The outer rings are things like the Subway, Times Square, Brokers’ Fees. The inner ones are things like Taxes, Grant Applications, Performance Art. Once you get past those, there is only one ring left, the innermost ring of Hell. And that ring is not this basement. That ring is what happens after this basement. That ring is the space of deceit and guilt that will be created the moment Camilo stops waving his arms. That ring is the thing that lies just ahead.

Afterward, we go to a bar down the street. Camilo’s friends are abuzz with excitement, in part because we’re finally out of the basement, mostly because we’re day-drinking. Camilo lets them talk to him about poignancy and the truths of the body, and then he turns to me. His eyes are wide, guileless, depthless. This is the moment he has been waiting for. Every cell of his body strains toward me. “What did you think?” he asks, desperately casual.

I smile at him. I force every cell of my body into an upward position. I try to radiate. I am thermonuclear.

“It was so interesting,” I say. “It was really really interesting.”

I meant to say good. I meant to say good. Why couldn’t I say good! I’d silently practiced the word good.