Excerpt

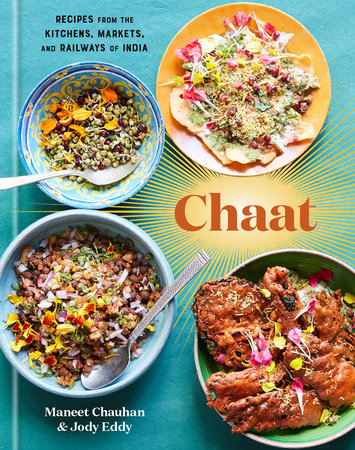

Chaat

Introduction The train wheels screech to a stop at the Jaipur Station. My mother, Hardeep, clasps my hand tightly, pulling me through the densely packed crowd of passengers also disembarking from the train. The sweltering air is thick with the bracing aroma of lemon and chiles. My anticipation grows as the sound of hundreds of chattering people fills my ears with a cloud of white noise until one piercing voice cuts through the chaos—the shrill cry of the bhel puri vendor, at last! My hungry eyes dart around, trying to locate the origin of the voice through a sea of vibrant saris and luggage porters clad in red linen shirts deftly balancing stacks of suitcases on their heads. There he is, behind a makeshift stand of metal tins overflowing with tomatoes, onions, cilantro, puffed rice, and limes. This man, a flavor alchemist, will transform these humble ingredients into an explosively delicious sweet, spicy, tangy, crunchy, creamy, and spicy snack called a chaat, the very chaat I dreamt about and pestered my mother about during the entire eight-hour train ride from New Delhi.

Chaat are the iconic snacks of Indian cuisine. A literal translation of the Hindi word

chaat is “to lick,” and chaat have therefore come to describe almost anything that is so good you find yourself licking the palm leaf or banana leaf that it was served on. Each train station in India has a unique specialty, a quick bite that is not only tasty but also represents the culinary traditions of the region. I adore chaat itself, and as an adult looking back on these experiences of traveling throughout India by train, I realize I not only ate deliciously well, but also learned about the food history of my nation through these humble dishes rich in nuance, regionality, and character.

My mother, a high school principal with an unwavering patience for my culinary desires, laughs and shakes her head as I drag her through the tightly packed throng of people, a human sea of motion, toward the bhel puri vendor. She knows me too well to deny me this singular pleasure. A crowd is gathered around him and I fear I will never get close enough to place my order. I bravely let go of my mother’s hand and use my tiny fingers to push through the swell of people until I am eye to eye with a bowl of crunchy, airy puffed rice. I inhale deeply and my nose fills with the scent of raw onions and mint chutney. I catch the vendor’s eyes through the telepathic strength of my longing just as I feel my mother’s hand on my shoulder. I do not break my gaze with him to acknowledge her because I fear that if I do the next bowl of bhel puri will not have my name on it. The vendor grins and nods at me before he begins his magic show. He spoons puffed rice—rice that has been heated with hot air (like popcorn kernels) until it puffs up and has an airy texture—into a bowl made of pressed palms. With a flourish, he tops it with crunchy chickpea noodles called sev, raw onions, tomatoes, boiled potato cubes, and cilantro. He sprinkles it with a chile powder and pungent chaat masala and drizzles it with vibrant tamarind andfiery mint chutneys.

My mother hands him a few rupees, about five cents, and I offer a smile as I reach greedily for the bhel puri. My mouth waters in anticipation of this bewitching marriage of flavors and textures that is crunchy one moment and soft and tender the next, offering a flash of tanginess that succumbs to the heat of chile before it is tempered by the sweet tamarind and cooled by the mint. I can’t focus on anything but getting a spoonful of bhel puri into my mouth until my mother leans down to my ear and whispers, “There is more to life than food, Maneet.” I stop to contemplate her words for a moment, wooden spoonful of bhel puri hovering in front my mouth. I suspect she might be right and wonder what a day that did not pivot around food would be like. I decide to ponder her words later. For now, my bhel puri commands my undivided attention.

I grew up in the small town of Ranchi in eastern India (map, page 19), the capital of the state of Jharkhand, famed for its malpua, crispy spiced pancakes drenched in sugar syrup. Every summer, my family embarked upon a long train ride to the steamy town of Bangalore in southern India to visit my maternal grandparents. For our winter holiday, the train took us north to my paternal grandparents’ home in Ludhiana, in the state of Punjab.

No matter whether we went north or south, our train journeys required two to three days of jangling over the rough steel tracks of the Indian rail network, a vestige of the British colonial era. The journey was typically a long, cramped, sweaty endeavor, but I never complained. This is because I knew every station delivered an endless picnic of chaat, inexpensive delicacies that my parents purchased from vendors clamoring for our rupees. Between stations, which for me translated as chaat stops, my sister would devour books while I daydreamed about food as well as the stories my father told me about his own experiences riding the rails in Russia, where he was occasionally sent for his job as an engineer. While the Russian dishes he described were different from the chaat of India, the romance for rail travel and culinary adventure was the same.

I first realized that food had power when I visited my older sister at university, arriving with containers stuffed with food that I had prepared at home before hopping on the train to reach her campus. I was only around fifteen at the time, but I realized at that young age that the person who brings the meal is the one who receives the love, and I craved seeing that first flicker of wonder and joy flashing in a person’s eyes. I might have realized food’s ability to conjure love from others in my teenage years, but my actual obsession with the flavors, textures, colors, and aromas of food was sparked during those formative train rides when I was just a girl.

At the stops we made during our train trips throughout India, snacks and chaat were always waiting for me, calling to me long before the train pulled into the station. On my mental map of India, the pins for each station conjure the taste memory of each chaat I devoured as a kid, each bite illuminating a chapter of the grand culinary history of my nation. I can’t wait for the day when my husband, Vivek, and I will bring our own children, Shagun and Karma, on a train journey through India. I hope it will inspire the same love that I have for my country and its cuisine.