Excerpt

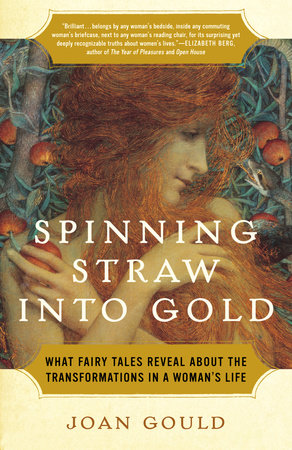

Spinning Straw into Gold

Chapter 1

Snow White: Breaking Away from Mother

The youngest heroine in this book, at least the youngest emotionally, is a girl who hasn’t yet completed her first transformation of consciousness: puberty, which eventually produces an independent sexual woman from a dependent child. Snow White’s body has begun to change by the time her story is under way—we know this from the violence of her stepmother’s reactions to her beauty—but her self-awareness hasn’t taken into account the biological upheaval starting to take place inside her.

Adolescence involves a break with the past, as well as a thrust toward the future. Without any choice, either too soon or too late to suit her, a girl loses the flat, lean body that she took for granted and finds that she has become a sexual creature, obscurely desired or threatened from all sides. At this stage, she must learn to see herself as separate from her background, her parents, and her home, with as few recriminations as possible toward those who made her what she is at present. She must picture a future different from the present, taking place against a background that she can’t visualize, in which she will answer to another name. Possibility opens up in front of her, dazzling her with its prospects, but at the same time she finds herself stripped of the protection she has taken for granted until now. Liberation is always a loss as well as a gain.

How, and when, do women get to know themselves as self-willed sexual beings, distinct from their families? By looking in a mirror, especially during adolescence, which is not at all the way a boy learns to know himself. Teenage girls peer into mirrors all day long to find out how others see them, what impact they’re going to have on the world around them, what can be improved or projected better or awaited, and what can only be deplored—critiques in the mirror’s voice that change from hour to hour. (“Flat,” says the mirror. “Still flat. You’ll never get a man, not with those goose bumps you call breasts. Why don’t you rethink your hair? Some streaks—that might be good. Or a French braid. And don’t stand like a Girl Scout at flag-raising. You want to smolder. . . . That’s better. You know what? You’ve got potential, girl. Your day is coming.”)

This isn’t the time-wasting obsession that adults think it is. Like it or not, an adolescent girl recognizes that she’s an object as well as a subject, a soul encased in a carcass that’s the material she was given to work with in order to attract a mate and advance nature’s program of making a mother of her.

At any age, can a woman stand in front of a mirror for more than thirty seconds and acknowledge herself simply as an object in space, without correcting her appearance in some way—running her fingers through her hair or wiping the corners of her lips—while making some silent comment about her looks, more often than not unfavorable?

In short, looks matter. We can manage to be more than the body, but there’s no way we can be less.

“Snow White” is a story about looks, looking and being looked at, a glittery tale of a window, a snowfall, a mirror, and a coffin made of glass. The females in it are a good mother who looks out the window at a fresh snowfall, a bad mother who looks only at her own reflection in the mirror, and a daughter who lies still as death and is looked at. But any story that deals with looks and looking is necessarily a story about time, which is a force that defeats beauty.

A girl named Snow White lives with her stepmother, a Queen obsessed with her own appearance, who possesses a magic mirror. But in a palace ruled by this mirror’s pronouncements as to who is the most beautiful in the land, how is it that the heroine has no mirror of her own, or, if she has one, lacks the heart to use it? Who has convinced her that her looks aren’t worth bothering about, since no one will pay attention to her anyway? While the Queen glories in her superiority, her stepdaughter, who is just coming into her own beauty, has no idea what she looks like, none of the usual self-consciousness of adolescence, which is how we know that she hasn’t yet gone through the turmoil that is about to engulf her.

A child’s first mirror is her mother’s eyes, which determine what reflections she’ll see for the rest of her life. If a mother admires her daughter—let’s say the girl is eleven or twelve years old and prepubescent—the girl learns to use an actual mirror as a tool for self-study. (I didn’t say if the mother “loves her daughter,” since we don’t know how to recognize love in its many guises. “Admires” is the operative word here.) She does this because of the confidence her mother pours into her.

Snow White, on the other hand, has no picture of her future as a sexual creature when we first meet her. Except for the Queen, she’s the only female in the palace; there are no siblings or friends, no other images of womanhood in front of her. Her stepmother is what it means to be female; her stepmother is Queen, but the girl is nothing like her stepmother and, what’s more, never will be, which means that there must be something the matter with her. The longer she scrutinizes the older woman, the more of an outcast she feels in a woman’s world, scrutiny being the female equivalent of male sparring as a way for two people of the same gender to gauge each other’s strength.

But there are sexually mature girls, there are even grown women, who don’t acquire their own mirrors because, for one reason or another, their vision has been blinkered by their mothers and they can’t bear to come face-to-face with their unaccepted and unacceptable selves.

“I was around fourteen—maybe fifteen—when my mother paid one of her rare visits to the house where I was being brought up by my grandmother,” said a friend of mine who is now the mother of three children. “I was coming out of the shower when she walked into the bathroom and saw me naked for the first time in six months. Maybe more. From her look of shock, I understood what she was seeing: my developing breasts, nipples that had grown darker and slightly puffy, pubic hair, rounded hips and belly. She left in a hurry and shut the door. I looked in the bathroom mirror, which had been there all along, of course, but I didn’t see beauty reflected back at me. I saw danger. I loathed the body that was causing this separation between us. From that time on, I did my best to make myself disappear: anorexia, hair hanging over my face, baggy T-shirts to hide those breasts. All the sad disguises. Not until I was in the delivery room years later, giving birth to my first child, did I understand the power and beauty of a woman’s body.”

Like many of the best-loved tales, the Grimms’ story of Snow White starts with a wish.

On a day in the middle of winter, a Queen sits beside her window, watching a snowstorm while she sews. Suddenly her needle slips, she pricks her finger, and three drops of blood fall upon the snow: always three, the magic number. The red drops look pretty on the snow, and she thinks to herself, “Would that I had a child as white as snow, as red as blood, and as black as the ebony window frame.”

White, red, black. Seeing nothing but snow in front of her, the original Queen, who is the Good Mother, has summoned the ancient trinity of colors to compose a wish-child. Together they form a series, putting us on notice in the opening sentences that this will be a magical story in which each color, in turn, will determine a stage in the life of the child created by the wish. The heroine, who will be more luscious than blood on snow—life on top of death—will move through three phases of life to reach a fourth stage her mother has never dreamed of—gold—while, at the same time, her future stepmother, who cannot stage-manage her own colors, will be nudged against her will from red into black.

At the moment when the Queen makes her wish, the earth sleeps beneath the falling snow, pure but barren, and awaits its reawakening the way Snow White will sleep in her glass coffin later on, and so the first color to appear on the scene has to be the heroine’s name: Snow White.

White is innocence, virginity, purity, light without heat, a window into the future, but white by itself is sterile. Something more than snow is required to produce life.

The child must also be as red as the drops of blood that flow from her mother’s finger. The Queen has felt a prick, just as Sleeping Beauty will be pricked by a spindle. “Prick” is a word we still use for penis; in street language, an upraised middle finger is understood as a sexual act. The Queen’s blood is the same as menstrual blood, so common that the loss is scarcely noticed, even though it signals life’s capacity to regenerate itself. But it’s also the blood that flows from a ruptured hymen when a woman loses her virginity and conceives a child, which is what has happened to the Queen here.

Blood is red, the womb is red, the vulva is red, especially when stimulated. Paleolithic cliff tombs were painted red, to show that the earth, the body of the goddess, is the womb of life as well as its tomb. Above all, sex is red, as in Eve’s apple, a virgin’s “cherry,” Persephone’s pomegranate or the Devil’s cloak, the red-light district, red shoes, red satin boxes shaped like hearts and filled with candies to be licked on Valentine’s Day, or a Scarlet letter A for adultery, embroidered in gold on a Puritan gown.

White and red together make a child’s story, as in “Snow White and Rose Red,” but a crucial element is lacking: the perspective of time. The Queen’s child must also be black as the window frame (black as a raven’s wing in other versions), a strange condition to insist on before birth, since black is the color of unconsciousness and death. Put together, the three colors paint a picture of time and growth, the phases of the moon as crescent, full, and waning, which correspond to the ancient goddess in her triple phases as Maiden, Matron, Crone.

These colors are on the earthly level, however, leading to the fourth and final color: gold. In “Snow White,” the golden element is hidden until the story is nearly over.

But fairy tales are no simpler than real life. The heroine can’t move directly from white to red, from childhood to sexuality, without passing through a period of blackness, which in the first three stories in this book—“Snow White,” “Cinderella,” and “Sleeping Beauty”—takes the form of either work or sleep.

Cinderella works while living among the ashes. Sleeping Beauty sleeps. Snow White does both, as she moves from her mother’s palace through the dwarfs’ cottage and into a coffin before finding a home of her own. In each case, an interval of darkness shrouds the heroine while she goes through her transformation from one plane of existence to the next.

This may be why we remember certain patches of childhood and adolescence vividly, and others not at all. Or why we remember ourselves at school—a junior-high actress starring in the school play, a girl in the cafeteria gossiping with friends, a success on the hockey field—but not as bodies at home. What we can’t remember happened during the dark spells, when we couldn’t bear to look at ourselves yet.