Excerpt

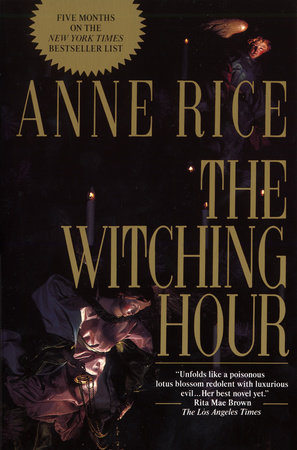

The Witching Hour

The doctor woke up afraid. He had been dreaming of the old house in New Orleans again. He had seen the woman in the rocker. He'd seen the man with the brown eyes.

And even now in this quiet hotel room above New York City he felt the old alarming disorientation. He'd been talking again with the brown-eyed man. Yes, help her.

No, this is just a dream. I want to get out of it. The doctor sat up in bed. No sound but the faint roar of the air conditioner. Why was he thinking about it tonight in a hotel room at the Parker Meridien? For a moment he couldn't shake the feeling of the old house. He saw the woman again—her bent head, her vacant stare. He could almost hear the hum of the insects against the screen in the old porch. And the brown-eyed man was speaking without moving his lips. A waxen dummy infused with life—

No, stop it. He got out of bed and padded silently across the carpeted floor until he stood in front of the sheer white curtains, peering out at black sooty rooftops and dim neon signs flickering against brick walls. The early morning light showed behind the clouds above the dull concrete façade opposite. No debilitating heat here. No drowsing scent of roses, of gardenias.

Gradually his head cleared.

He thought of the Englishman at the bar in the lobby again. That's what had brought it all back—the Englishman remarking to the bartender than he'd just come from New Orleans, and that certainly was a haunted city. The Englishman, an affable man, a true Old World gentleman it seemed, in a narrow seersucker suit with a gold watch chain fixed to his vest pocket. Where did one see that kind of man these days?—a man with the sharp melodious inflection of a British stage actor, and brilliant, ageless blue eyes.

The doctor had turned to him and said: "Yes, you're right about New Orleans, you certainly are. I saw a ghost myself in New Orleans, and not very long ago—" Then he had stopped, embarrassed. He had stared at the melted bourbon before him, the sharp refraction of light in the base of the crystal glass.

Hum of flies in summer; smell of medicine.

That much Thorazine? Could there be some mistake? But the Englishman had been respectfully curious. He'd invited the doctor to join him for dinner, said he collected such tales. For a moment, the doctor had been tempted. There was a lull in the convention, and he liked this man, felt an immediate trust in him. And the lobby of the Parker Meridien was a nice cheerful place, full of light, movement, people. So far away from that gloomy New Orleans corner, from the sad old city festering with secrets in its perpetual Caribbean heat.

But the doctor could not tell his story.

"If you ever change your mind, do call me," the Englishman had said. "My name is Aaron Lightner." He'd given the doctor a card with the name of an organization inscribed on it: "You might say we collect ghost stories—true ones, that is."

The Talamasca

We watch

And we are always here. It was a curious motto.

Yes, that was what had brought it all back. The Englishman and that peculiar calling card with the European phone numbers, the Englishman who was leaving for the Coast tomorrow to see a California man who had lately drowned and been brought back to life. The doctor had read of that case in the New York papers—one of those characters who suffers clinical death and returns after having seen "the light."

They had talked about the drowned man together, he and the Englishman. "He claims now to have psychic powers, you see," said the Englishman, "and that interests us, of course. Seems he sees images when he touched things with his bare hands. We call it psychometry."

The doctor had been intrigued. He had heard of a few such patients himself, cardiac victims if he rightly recalled, who had come back, claiming to have seen the future. "Near Death Experience." One saw more and more articles about the phenomenon in the journals.

"Yes," Lightner had said, "the best research on the subject has been done by doctors—by cardiologists."

"Wasn't there a film a few years back," the doctor had asked, "about a woman who returned with the power to heal? Strangely affecting."

"You're open-minded on the subject," the Englishman had said with a delighted smile. Are you sure you won't tell me about your ghost? I'd so love to hear it. I'm not flying out till tomorrow, sometime before noon. What I wouldn't give to hear your story!"

No, not that story. Not ever.

Alone now in the shadowy hotel room, the doctor felt fear again. The clock ticked in the long dusty hallway in New Orleans. He heard the shuffle of his patient's feet as the nurse "walked" her. He smelled that smell again of a New Orleans house in the summer, heat and old wood. The man was talking to him—

The doctor had never been inside an antebellum mansion until that spring in New Orleans. And the old house rally did have white fluted columns on the front, though the paint was peeling away. Greek Revival style they called it—a long violet-gray town house on a dark shady corner in the Garden District, its front gate guarded it seemed by two enormous oaks. The iron lace railings were made in a rose pattern and much festooned with vines—purple wisteria, the yellow Virginia creeper, and bougainvillea of a dark, incandescent pink.

He liked to pause on the marble steps and look up at the Doric capitals, wreathed as they were by those drowsy fragrant blossoms. The sun came in thin dusty shafts through the twisting branches. Bees sang in the tangle of brilliant green leaves beneath the peeling cornices. Never mind that it was so somber here, so damp.

Even the approach through the deserted streets seduced him. He walked slowly over cracked and uneven sidewalks of herringbone brick or gray flagstone, under an unbroken archway of oak branches, the light eternally dappled, the sky perpetually veiled in green. Always he paused at the largest tree that had lifted the iron fence with its bulbous roots. He could not have gotten his arms around the trunk of it. It reached all the way from the pavement to the house itself, twisted limbs clawing at the shuttered windows beyond the banisters, leaves enmeshed with the flowering vines.

But the decay here troubled him nevertheless. Spiders wove their tiny intricate webs over the iron lace roses. In places the iron had so rusted that it fell away to powder at the touch. And here and there near the railings, the wood of the porches was rotted right through.

Then there was the old swimming pool far beyond the garden—a great long octagon bounded by the flagstones, which had become a swamp unto itself with its black water and wild irises. The smell alone was frightful. Frogs lived there, frogs you could hear at dusk, singing their grinding, ugly song. Sad to see the little fountain jets up one side and down the other still sending their little arching streams into the muck. He longed to drain it, clean it, scrub the sides with his own hands if he had to. Longed to patch the broken balustrade, and rip the weeds from the overgrown urns.

Even the elderly aunts of his patient—Miss Carl, Miss Millie, and Miss Nancy—had an air of staleness and decay. It wasn't a matter of gray hair or wire-rimmed glasses. It was their manner, and the fragrance of camphor that clung to their clothes.

Once he had wandered into the library and taken a book down from the shelf. Tiny black beetles scurried out of the crevice. Alarmed he had put the book back.

If there had been air-conditioning in the place it might have been different. But the old house was too big for that—or so they had said back then. The ceilings soared fourteen feet overhead. And the sluggish breeze carried with it the scent of mold.

His patient was well cared for, however. That he had to admit. A sweet old black nurse named Viola brought his patient out on the screened porch in the morning and took her in at evening.

"She's no trouble at all, Doctor. Now, you come on, Miss Deirdre, walk for the doctor." Viola would lift her out of the chair and push her patiently step by step.

"I've been with her seven years now, Doctor, she's my sweet girl."

Seven years like that. No wonder the old woman's feet had started to turn in at the ankles, and her arms to draw close to her chest if the nurse didn't force them down into her lap again.

Viola would walk her round and round the long double parlor, past the harp and the Bosendorfer grand layered with dust. Into the long broad dining room with its faded murals of moss-hung oaks and tilled fields.

Slippered feet shuffling on the worn Aubusson carpet. The woman was forty-one years old, yet she looked both ancient and young—a stooped and pale child, untouched by adult worry or passion.

Deirdre, did you ever have a lover? Did you ever dance in that parlor?