Excerpt

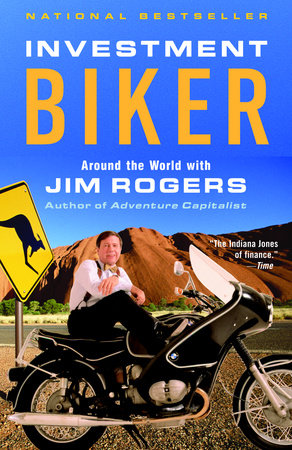

Investment Biker

I was born in 1942, the eldest of five brothers. My parents met in the thirties at the University of Oklahoma, where both belonged to academic honor societies. During the war, my father served as an artillery officer in Germany. After the war, he joined his brother in running a factory in Demopolis, Alabama, a state in which my people had lived since the early nineteenth century.

With the birth of so many boys, my mother, an only child, was rapidly in over her head. She made us competitive and full of high jinks. The five of us learned drive from our father, who taught us to push to make happen whatever it was we wanted to do. From him we learned how to work hard.

My entrepreneurial efforts started early. I had my first job at the age of five, picking up bottles at baseball games. In 1948 I won the concession to sell soft drinks and peanuts at Little League games. At a time when it was a lot of money, my father gravely loaned his six-year-old son one hundred dollars to buy a peanut parcher, a start-up loan that put me in business. Five years later, after taking out profits along the way, I paid off my start-up loan and had one hundred dollars in the bank. I felt rich. (I still have the parcher. Never know when such a dandy way of making money might come in handy.)

With this one hundred dollars, the investment team of Rogers & Son sprang into action. We ventured into the countryside and together purchased calves, which were increasing in value at a furious rate. We would pay a farmer to fatten them, and sell them for a huge profit the following year.

Little did we know that we were buying at the top. In fact, only twenty years later, on reading one of my first commodity chart books, did I understand what had happened. My father and I had been swept into the commodities boom engendered by the Korean War. Our investment in beef was wiped out in the postwar price collapse.

I did well in our isolated little high school, finishing at the top of my class. I won a scholarship to Yale, which thrilled and terrified me. How would I ever compete with students from fancy Northeastern prep schools?

When I went to Yale, my parents couldn’t take me up to New Haven. It was too far. So on that first Sunday, when all college students are supposed to call home, I got on the phone and told the operator I wanted to call Demopolis, Alabama. She said, “Okay, what’s your phone number?”

I said, “Five.”

She said, “Five what?”

“Just five.”

She said, “You mean 555-5555?”

“No,” I said politely, “just five.”

She said, “Boy, are you in college?”

“Yes, ma’am.”

She blazed, “I don’t have to take this from you, college boy!”

Finally, persuaded I meant no disrespect, she gave it a try. This was back in the days when the Connecticut operator had to get the Atlanta operator who had to get the Birmingham operator who finally got the Demopolis operator on the phone.

My Connecticut operator spoke first. “I’ve got a boy on the line who says he’s trying to reach phone number five in Demopolis, Alabama.”

Without missing a beat, the Demopolis operator said, “Oh, they’re not home now. They’re at church.” The New Haven operator was stunned speechless.

As my college years sped by, I considered medical school, law school, and business school. I loved learning things, always have, and I certainly wanted to continue to do so. In the summer of 1964 I happened to go to work for Dominick & Dominick, where I fell in love with Wall Street. I had always wanted to know as much about current affairs as I could, and I was astounded that on the Street someone would pay me for figuring out that a revolution in Chile would drive up the price of copper. Besides, I was poor and wanted money in a hurry and it was clear there was plenty of money there.

At Yale I was a coxswain on the crew, and toward the end of my four years I was lucky enough to win an academic scholarship to Oxford, where I attended Balliol College and studied politics, philosophy, and economics. I became the first person from Demopolis, Alabama, to ever cox the Oxford-Cambridge Boat Race on the Thames.

I began to use some of what I had learned in my summer job on Wall Street, investing my scholarship dollars before I had to turn them in to the Balliol bursar.

After Oxford I went into the army for a couple of years, where I invested the post commander’s money for him. Because of the bull market, I made him a tidy return. I came back to New York and went to work on Wall Street.

I eventually became the junior partner in a two-man offshore hedge fund, which is a sophisticated fund for foreign investors that both buys and sells short stocks, commodities, currencies, and bonds located anywhere in the world. I worked ceaselessly, making myself master as much as possible of the worldwide flow of capital, goods, raw materials, and information. I came into the market with six hundred dollars in 1968 and left it in 1980 with millions. There had been costs, however. I had had two short marriages to women who couldn’t understand my passion for hard work, something my brothers and I had inherited from our father. I couldn’t see the need for a new sofa when I could put the money to work for us in the market. I was convinced, and I still am, that every dollar a young man saves, properly invested, will return him twenty over the course of his life.

In 1980 I retired at the ripe old age of thirty-seven to pursue another career and to have some time to think. Working on Wall Street was too demanding to allow reflection. Besides, I had a dream. In addition to wanting another career in a different field, I wanted to ride my motorcycle around the entire planet.

I’d always wanted to see the world once I realized Demopolis, Alabama, really wasn’t the center of the Western World. My longtime lust for adventure probably came from the same source. But I saw such a trip not only as an adventure but also as a way of continuing the education I had been engaged in all throughout my life—truly understanding the world, coming to know it as it really is. I would see it from the ground up so that I would really know the planet on which I walked.

When I take a big trip, like a three-month drive across China, Pakistan, and India, the best way to go is by motorcycle. You see sights and smell the countryside in a way you can’t from inside the box of a car. You’re right out there in it, a part of it. You feel it, see it, taste it, hear it, and smell it all. It’s total freedom. For most travelers the journey is a means to an end. When you go by bike, the travel is an end in itself. You ride through places you’ve never been, experience it all, meet new people, have an adventure. Things don’t get much better than this.

I wanted a long, long trip, one that would wipe the slate clean for me. I still read The Wall Street Journal and the Financial Times, and I wanted to wean myself away from the investment business. I wanted a change of life, a watershed, something that would mark a new beginning for the rest of my life. I didn’t know what I would do when I got back, but I wanted it to be different. I figured a 65,000-mile ride around the world ought to be watershed enough.

In 1980 it was difficult to circle the planet—you couldn’t get anywhere. There were twenty-five to thirty wars going on, and the Communists wouldn’t let you pass through Russia or China. If I were going to go around the world, it was going to be like everything I do: I was going to do it to excess or not at all. My dream was to cross six continents completely—west to east across China, east to west across Siberia, from the top of Africa to the horn, across Australia’s vast desert, and from the bottom tip of Argentina right up to Alaska.

In 1984 and 1986 I went to China to approach officials about crossing the country. I even rented a motorcycle, a little 250-cc Honda, and drove around Fujian province to see what I could learn. Fujian wasn’t all that big, maybe the size of Louisiana, but with 26 million inhabitants it had almost seven times Louisiana’s population. I drove and flew to several provincial capitals, and put two thousand miles on that bike as research. Then, at last, in 1988, I drove clear across China on my own bike.

Back in New York, I went to see the Russians, as I’d often done before. Russia was still the big stumbling block to a drive around the world. I wrote letters and got others to write testimonials on my behalf. I hit an absolute stone wall. I’d go down to Intourist, and Ivan Kalinin, the director, would tell me it wasn’t even conceivable. There’s nothing out there in Siberia, he’d say, except bears and tigers and jungle and forest. Nobody goes there, nobody wants to go there, and in fact, all the people the Russians sent there had wanted to come back.

To my astonishment, no Russian I’d met had ever been to Siberia or knew anyone who had. No Soviet citizen seemed to have a clue as to what was in his equivalent of our nineteenth-century Wild West, just as most New Yorkers today know nothing about Alaska. Take the train, the Russians told me—the Trans-Siberian Railroad—or fly. Only a fool or a madman would drive.

I finagled a proper introduction to the Russian ambassador in Washington, but even he was no help.