Excerpt

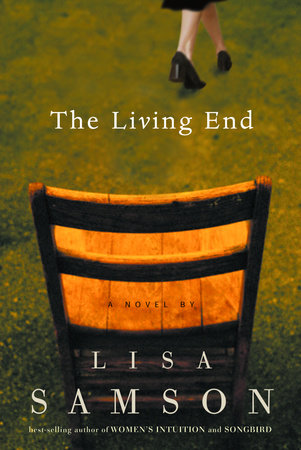

The Living End

December

My definition of beauty? Jimmy Stewart and Donna Reed in any one of a number of embraces during the holiday film

It’s a Wonderful Life. Keep your pyramids, your mountain ranges, and your gems and jewels. The planes of those two faces, not flawless by any means when compared to the likes of Errol Flynn and Grace Kelly, mesh to form perfection. In a sense, perhaps their lives—well, their characters’ lives at any rate—mesh to form perfection as well. And isn’t that the point of the movie?

I sit and cry as I do every year, weeping as George Bailey, having seen life without his existence, runs through town screaming with joy and yelling, “Merry Christmas!” Joey runs his fingers through my hair, sniffing, and wiping his eyes with his other hand. I know what he’s thinking. He’s thinking what a wonderful life

we have, naturally. For who can watch this movie and not celebrate the fact that they merely exist in this big old wonderful world?

September

How is it I’ve come to be sitting here in this aspirin room, hovering inside my own nervous energy?

“We’ve done all we can.”

I shake my head, a gelatin shake, more vibration than information. In direct opposition to my movement, the doctor slowly nods.

“I’m sorry to have to tell you, Mrs. Laurel, that there isn’t any more we can do for your husband. The most we can do now is make him comfortable.”

“How much longer will it be?” Vibrating words cricket-hop across my tongue, springing out into oxygen in which the odor of bodily secretions, feces, puke, urine, and spilled solutions have been masked by cleaning products. I’ve been reading the labels on these things the past twenty-four hours, and it amazes me they don’t eat right through their containers. “How much longer, then?”

“Three days, maybe four or five. Could be today. I regret not being able to tell you anything more specific.”

Not Joey. Not my Joey. My lively Joey, for thirty-five years now. The doctor’s hands display no wrinkles.

The sterility in here disconcerts me. Yet an earthiness pervades because diseases are living things. They do not infect linoleum that cannot die, or sliding glass doors, or ball-bearing–lined curtain rings. So cold and standoffish, these things. Unworthy even of death. Only the living deserve to die. In a way, maybe death is the ultimate compliment.

Maybe Joey’s right where he belongs. The friendliest guy in the world, yes sir, that’s what everybody said about Joey. So full of life, curiosity, and contentment. And after all these years, I can only agree. This room crushes his persona.

I feel old now and sweaty and stinky in this clean hospital room. We always loved a clean house, Joey and me, which is probably why we never adopted after I came down with cervical cancer and underwent an early hysterectomy. Joey held me after the surgery, and I cried.

I want to hold him now and have him feel my love and commitment and maybe even what little strength remains, the way I did when he held me in his bamboo arms. Just one more time, I want to see the moist sparkle that never left his eyes. Oh, he’s been a saucy thing all these years. If I had a dollar for every time he swatted my behind, the tomcat, I’d be richer than a headmaster’s wife ought to be!

I wonder how the folks at the school are taking this?

I haven’t called them!

Nobody knows but me.

But this is good.

The doctor fidgets with his lab coat lapel. “You have the option to remove him from life support, Mrs. Laurel.”

“Is he suffering now?”

“No.”

“Then keep him on.”

I dream all the time about suffocating. Some people dream about drowning. Some dream about fire. Others have falling dreams and crashing dreams, suicide dreams and bomb dreams. Shooting dreams and stabbing dreams and dying dreams.

Oh, dear God.

Would he suffocate without the ventilator? Would he somehow feel it, somehow know I made the decision? I mean, people say all the time after they wake up out of comas that they heard everything going on in the room. One time one of Joey’s students, a boy named Spike, told us when he was seven he—

“You might want to do whatever you need to do to prepare yourself, Mrs. Laurel. We have a wonderful social worker and a chaplain here who can help you. Again, I’m so sorry.”

He leaves the room with his callow head hanging a bit. It was one thing when the policemen started looking young, but now the doctors blush with youth and an uncertainty only the older folk detect. Joey and I always laugh about it, though. We love growing old together. He calls us “The Coots.” Of course, he’s been calling us The Coots since I turned thirty-five and he was about to turn the ripe old age of forty-one.

Twenty years ago.

It’s not often that I wish to go back in time, but right now?

There we’d been, lunching at the Golden Corral yesterday, and Joey fell face forward into the strawberry-gelatin-with-bananas salad. Right there at the salad bar. A stroke. Massive they said.

But Joey never does anything halfway. If cyclones actually left places better than they found them, they would resemble Joey. I keep reliving the conversation that preceded the incident. Joey’s eyes glowed like they do when excitement surges inside him. Which happens often. With a rise of his brows, he pulled from his pocket a piece of paper, the object of much thought, judging by the chamois texture of its folds. “I have news, Pearly.”

I remember feeling the emotion I’d felt so many times with my husband: that childlike expectation, that hippity-hop dance of the brain that would jangle down into my limbs each time my parents and I waited in line on the amusement pier at the ocean. The lights blinked in time with my heart, and the smell of caramel corn and hot dogs and cotton candy rose on the salty air of the warm sea breeze above the smell of tar and creosote and Coppertone. Oh, Joey’s made life a carnival, that’s for sure, with his verve, his zest, his tap dance of an existence. All this and a brain to boot.

I catch my reflection in the sliding glass doorway of the hospital room. I haven’t slept since the stroke occurred and they flew him here to shock trauma. My hair foams from atop my head down to the bottom of my chin in a silver halo of disarray. My jeans gap around my middle, my waistband far away from my empty stomach. I am haggard and starved of so much right now, wispy and insignificant in this large complex. One of the many suffering molecules in the mass of humanity. I look as old as Joey. And almost as gray.

At least his face shines smooth and clean. I wiped off the salad before the paramedics arrived. That would have humiliated Joey, to be found with that substance glistening on his face.

I reach for a wet wipe and freshen my face and neck, but the paper cloth heats up too quickly. I throw it in a garbage can filled with tubing and empty foil-lined packets. Such crisp edges define their boundaries, nothing like the paper Joey pulled from his pocket yesterday afternoon.

He held out the paper. “Take it, read it, and tell me what you think. Personally, I think it’s rather brilliant.”

I laughed. “Joey, you think everything is brilliant.” Which explains why he married me. The man is hardly choosy.

“Open it. I’ll pretend to ignore you while you read.”

There before my eyes marched a list, typed out on Joey’s old Selectric with the script type ball. Remember those days? I thought my job at the insurance agency couldn’t get any easier than that!

But then computers came, and my goodness, that old Selectric, all one hundred and fifty pounds of it, became a horse and buggy almost overnight. Joey always has admired my ability to keep up with technology in office machinery.

Oh, the list. He was right. Brilliant. Up at the top, in all caps, which does look a bit odd in script, are the words WHILE I LIVE I WANT TO…

A nurse enters on white rubber clogs, but I hear her. “Hi, Mrs. Laurel.”

“Hi…Cindy, is it?”

“Yes. How’s our man?”

“The same.” I shrug.

“Well, let me hang another bag, and I’ll leave you alone.”

“No hurry.”

She props reading glasses on her nose, then pushes buttons on the IV machine. She turns, her cherubic yet lined face beautiful even in the sickly, fluorescent light shining from above the bed.

“Are you hungry? I can order up a tray for you.”

“No, thank you.”

Her beeper sounds, and she checks the code. “Well, honey, let me know if you change your mind, okay?”

I just nod. I’m not up to much more, really. After she pads out, I pull Joey’s list from my pocketbook. Darn it, I wish he had written it out in his own hand. I could really use the sight of that right now. But they are his words, at least, and I run my fingers over the black letters and read them again.

1. Go whale watching in Alaska.

2. See the mysterious figures on the plains of Peru.

3. Climb a pyramid in South or Central America.

4. Walk the Appalachian Trail.

5. Spend a winter on a mountain.

6. Try every entrée at Haussner’s.

I had laughed at this. “Joey, we’ll be going to Haussner’s for years if we do this!”

“Exactly! Brilliant, isn’t it? I’ve always wanted to be a regular at that restaurant.”

I looked around at the cheesy steakhouse décor. “Well, we may have to curtail our trips here.”

“That’s true. But I think we’ll manage.” He sat back and leisurely sipped on his tea. I read the last item and smiled.

7. Get a tattoo.

“So, what do you think, my dear? Are you game?”

“For the list? Well, of course!”

“Won’t we have a wonderful time?”

“Yes, Joey. When do we start?”

He sat forward. “This is my news: I’m thinking about retiring from Lafayette.”

I couldn’t believe my ears. “But…well, my goodness. Isn’t this sudden?”

He nodded. “Yes. But I’ve been thinking lately. You’ve given up your entire life for me, Pearly. And now, well, let’s simply enjoy each other, travel, complete something

together.”

“This list?”

“Precisely. Can you imagine the pictures you’ll take, my dear?”

I blushed. “Oh, Joey, I haven’t taken out my camera in years.”

“Then it’s time to now, don’t you think?”

I cocked my eyebrow. “Is this your annual ‘You need to start taking pictures again, Pearly’ conversation? Because if it is…you’re going a little extreme here with all these things to do. There must be a less expensive way to convince me.”

“Are they at least activities you think you can stomach?”

I ran my fingers down the list. “Yes. The whole South American angle is a bit mysterious, though, Joey. I never knew that interested you.”

He smiled and took my hand. “Well, to be honest, Pearly, I actually put some of these down for you, too.”

“But why would South—”

“Hold that thought. You know, I think I’d like a little more of that broccoli salad. Would you like something else?”

And he walked away. Really walked away. But I watched him go, as I always do, fascinated by him even after all these years. Oh, my, I love this man so much, love the way his smile never quite leaves his face, the way the cowlicks at the back of his head make a C—well, made a C before he went bald—the way he’s stayed so trim and fit, and how many women my age actually are married to a man with a flat stomach and a nice firm tush? But Joey’s blue eyes, faded now, never cease to find the good, the beautiful, and the righteous, even in the most unlovely of places. And now here I sit in a hospital room.

Before I place the list back in my pocketbook, I run my index finger along its folded edges, rubbing, rubbing, fraying the edges further. Turning off the light over the bed, I wait now. I gaze at the rose-colored vinyl lounge chair, my pillow still indented where my head once lay. No heartbeat thumped through the pillow last night the way it always thumps through Joey’s T-shirt when I drift off against his chest. I wonder if sleep will ever own me again, or if it will see itself as merely a surprise visitor, a wayward cousin coming only when I least expect it.

What abrades my well-being the most right now is that Joey has lost his scent. I haven’t been home to stuff my nose into his pillow or his winter coat. I’d stick my nose into his old running shoes if I could. Everything smells like hospital here. Even Joey.

So I perch on my chair and tuck his slender hand inside mine. It’s cool. Sickly city daylight filters through the drawn blinds in vertical strands.

“Where are you, Joey?” The sound of my own voice, soft yet intrusive in this room, embarrasses me. What will the nurses think if they catch me talking to an unconscious person? I never liked the sound of my voice anyway, too thin and trepid, and it skips sometimes. It seems more wrong than ever here.

Can you hear me, lovey? Do you know I’m here? How long will you stay?

I don’t know what happens after death. But if anyone can come back and tell me, it’ll be Joey. He loves to teach.

Oh, God.

I can’t quite tell if I’m praying or cursing right now. I think it’s a prayer. I really do. And I’m sure Joey needs some. So I say, “Oh, dear God, I pray to You,” just to make sure. And nothing else comes to mind.