Excerpt

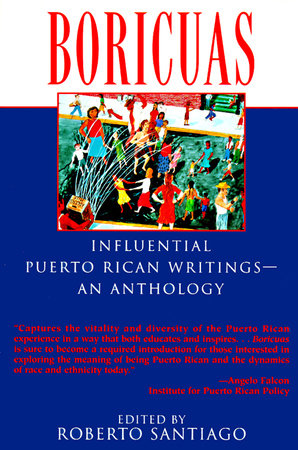

Boricuas: Influential Puerto Rican Writings - An Anthology

INTRODUCTION

“I am two parts/a person/boricua/spic/past and present/alive and oppressed …”

—SANDRA MARIA ESTEVES

FROM HERE

For years, I was called a Boricua, never knowing what it meant. Boricua was what old men playing dominoes by the candy store called one another between smiles and sips of cold malta. Boricua was what local politicians told everyone in the neighborhood that they were when election time rolled around. Boricua was what nationalist activists chanted when they marched down Fifth Avenue during the Puerto Rican Day Parade. But above all, Boricua was the word that turned strangers into friends when used as a greeting. Whether it was addressed to a wealthy Puerto Rican man in Ponce or a Puerto Rican from the South Bronx, Boricua had the same indisputable impact.

I imagined that Boricua was just affectionate slang for Puerto Rican. I guessed that Boricua was just a word that proclaimed that you were down with your people and your culture—no different from brother and sister, the terms of endearment used by African Americans.

In New York City’s Spanish Harlem in the 1960s and 1970s, guessing was the only way Puerto Ricans like me figured out our culture and history. School was a place where we learned about everyone else except ourselves. We learned about the Fourth of July and how the United States was founded by English people who proclaimed that, in this nation, all men were created equal. We learned about how the Europeans shared dinner with the Indians on Thanksgiving. We learned about Christianity and how people who hold Christian values treat one another with love and respect. We learned about the environment and how important it is to keep the air and water clean.

But who we were as a people was never a consideration; it was a question that seldom entered our minds. Every other group except the Puerto Ricans—the Italians, the Irish, the Jews, the African Americans—seemed to have an idea who they were.

I’ll never forget talking to a Jewish boy on the subway, who, like me, was nine years old. Proudly, he told me that he went to something called a “Yeshiva” school where he learned about the history of his people, about something called “oppression,” and about how it was the responsibility of every Jewish person to rise and triumph no matter what the world dished out.

I’ll never forget my confusion when he asked me what Puerto Rican culture and history was all about and what made Puerto Ricans special on this planet. All I could think of was salsa music, rice and beans, and the palm trees of Puerto Rico. How that boy stared at me. I remember wishing that there was a Yeshiva for Puerto Ricans so I could learn the answers to the boy’s questions.

I wanted to find out what made Puerto Ricans special, but asking such questions in school only seemed to make teachers angry, especially the nuns and priests. At Commander Shea Grammar School in Spanish Harlem, a nun told me that Puerto Ricans had no culture. She made me feel stupid for even asking the question. “Oppressed,” a priest told me, was what lazy people said they were so they could blame other people for their problems.

Twenty years later, as a reporter and thus entitled to ask as many questions as I wished, I stood in Havana, Cuba, talking with political exile Guillermo Morales, one of the leaders of the Puerto Rican revolutionary group, the FALN (Armed Forces for National Liberation). Morales was remembering his own experience in grade school. When he told his teacher that he wanted to do a report on Puerto Rican history instead of British or American history, the teacher laughed and told him that Puerto Rican people had no history.

Then I remembered an interview I’d read about Puerto Rican writer Abraham Rodriguez, Jr. He’d been told by a teacher that there was no such thing as a Puerto Rican writer.

It seemed that we were a worthless people. We had no history. No culture. No identity. And there were so many of us around, too, in cars, on the streets, crowded into small apartments. We would say that we were proud to be Puerto Rican, but we couldn’t say why. And yet, I realized how powerfully we were all tied together by a common bond: the struggle to claim our identity against all odds.

I looked all around and I saw this mixture of colors, of languages, of ages; I saw integrity and docility, poverty and wealth, faith and frustration, humor and pain. But most of all, I saw fear. Fear rising from ourselves and others when we Puerto Ricans did something out of the ordinary. I saw that same fear when Puerto Ricans stood up and gave a speech that moved crowds. And I saw that fear again when Puerto Ricans waved poems they wrote and read them aloud.

One question began to haunt me: “What makes Puerto Ricans special on this planet?” I knew there had to be answers; I just hadn’t found them yet.

In New York City I attended Xavier High School, an all boys, semi-military school run by the Jesuits. There, the priests taught me about patriotism, Christian values, and the military. I was shown a flag, told that I was an American, and that I should love my country and die for it. Then I was shown a crucifix and told I should turn the other cheek when faced with injustice. Finally, they told me that I was a Son of Xavier, that I belonged. But out in the halls I was called “nigger” and “spic” by the white boys who attended the school. And the Jesuits just looked the other way.

My classmates told me that I should go back where I came from.

That my people were all lazy welfare and food stamp cheats.

That my people were too stupid to learn English.

Over and over again, it was reinforced that being white meant being superior. Only years later did I realize that—if it hadn’t been for their white skin—some of my classmates would have had nothing going for them.

Racism either makes you withdraw from yourself, hate yourself, or discover yourself. It was in the solitude of the Aguilar Library on 110th Street between Lexington and Third Avenue that I discovered myself through an odyssey of pain. Driven to books by the hatred and ignorance all around me, I read to survive. It was in that library that I first read Fidel Castro and Che Guevara and embraced progressive politics. It was in that library that, by accident, I discovered that there really were Puerto Rican writers.

Puerto Rican writers! Even now, years later, they still seem so subversive. All around me was this body of work: Puerto Rican poets and novelists, Puerto Rican orators, journalists, and academics. Puerto Rican playwrights, humorists, and essayists. Puerto Ricans wrote all these amazing things in all these great books, just like white people.

I felt a surge of excitement when I pulled from the shelves works from Piri Thomas, Pedro Pietri, Julia de Burgos, Jesus Colon, Miguel Piñero, Lola Rodriguez de Tio, Eugenio María de Hostos, Pedro Albizu Campos, Luis Muñoz Marín, José Luis Gonzalez. I held the stack of books in my arms for a long time, enjoying its weight. I let them tumble onto the desk. I watched these books by Puerto Rican writers spill over books by William Faulkner and Virginia Woolf, knowing that I was participating in a very solemn ceremony that would change my life forever. Oblivious to everyone around me, I saw only the books by Puerto Rican writers.

As fate would have it, the first book I read by a Puerto Rican author was the one the Jesuits at Xavier had denounced as pornographic and prejudiced against whites. I knew it had to be good. It was. The book was Down These Mean Streets, the autobiography of Puerto Rican writer Piri Thomas. He’d written about growing up in Spanish Harlem in the 1940s, but his experience was no different than mine thirty years later in the 1970s. And then there was that chapter, “Babylon for the Babylonians,” where Thomas, a black-skinned Puerto Rican, faces his first painful encounter with a racism he doesn’t understand, through the vicious words of a young white girl who masks her hatred with a smile.

Thomas’s story brought back my own painful memories of racism, which I later wrote about in my essay, “Black and Latino”:

My first encounter with this attitude about the race thing rode on horseback. I had just turned six years old and ran toward the bridle path in Central Park as I saw two horses about to trot past. “Yea! Horsie! Yea!” I yelled. Then I noticed one figure on horseback. She was white, and she shouted, “Shut up, you f______g nigger! Shut up!” She pulled back on the reins and twisted the horse in my direction. I can still feel the spray of gravel that the horse kicked at my chest. And suddenly she was gone. I looked back, and, in the distance, saw my parents playing Whiffle Ball with my sister. They seemed miles away.

As I read Down These Mean Streets, I no longer felt alone. Through Piri Thomas’s pain I was able to relive what I had so long suppressed, and this gave me new strength.

I read Pedro Pietri’s “Puerto Rican Obituary” and understood for the first time what it meant to have to live in poverty. There I was, living in the Taft Projects on 114th Street and Madison Avenue, but it wasn’t until I read this poem that I truly understood the reality of my surroundings.