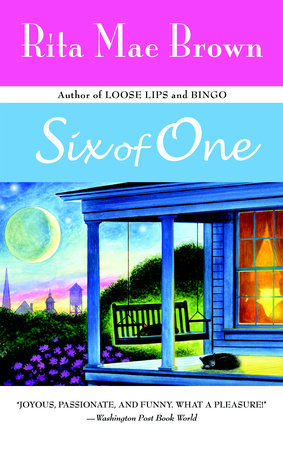

Excerpt

Loose Lips

Life will turn you inside out. No matter where you start you'll end up someplace else even if you stay home. The one thing you can count on is that you'll be surprised.

For the Hunsenmeir sisters, life didn't just turn them inside out, it tossed them upside down, then right side up. Perhaps it wasn't life whirling them around like the Whip ride at the fair. They upended each other.

April 7, 1941, shimmered, a light wind sending Louise's tulips swaying. Spring had triumphantly arrived in Runnymede, which straddled the Mason-Dixon line. The residents of this small, beautiful town, built around a square before the Revolutionary War, waxed ecstatic since springtime warmth had arrived early this fateful year. Probably every year is fateful to someone or other, but some years everyone remembers. On April 7, though, Fate seemed far away, shaking up countries across the Atlantic Ocean.

Julia Ellen, "Juts," slammed the door to her sister Louise's house. She pursed her lipstick-coated lips and blew a low note then a higher note, like a towhee bird. Snotty bird-watchers like Orrie Tadia Mojo, Louise's best friend from her schoolgirl days, called it a Rufous-sided towhee. Juts always pronounced it two-ey, since it uttered the note twice.

Hearing no response, Juts whistled again. Finally she yelled, "Wheezer, where the hell are you?" Still no answer.

Juts had celebrated her thirty-sixth birthday on March 6. She'd always possessed megawatts of energy, but as she zoomed through her thirties she accumulated even more energy, the way some people accumulated wrinkles. The only person who could keep up with her was Louise, four years older; since Louise lied shamelessly about her birthday everyone "forgot" her exact age except Juts, who held it in reserve should she need to whack her sister into line. Cora, their mother, remembered also but she was far too sweet to remind her elder daughter, who was having a fit and falling in it over turning forty. This momentous occasion had just occurred on March 25. Even Juts, out of pity, pretended Louise was thirty-nine at the birthday party.

Both sisters roared through life, although they roared in different keys. Juts was definitely a C major while Louise, an E minor, could never resist a melancholy swoon.

Juts stubbed out her Chesterfield in the glass ashtray with the thin silver band around the edge.

"Louise!" she shouted as she opened the back door and stepped out.

"I'm up here," Louise called from the roof.

Julia craned her neck; the sun was in her eyes. "What are you doing up there? Oh, wait, why should I ask? You're singing 'Nearer My God to Thee.'"

"I'll thank you to shut your sacrilegious mouth."

"Yeah, yeah, you walk on water. I came over here to take you to lunch at Cadwalder's but you're such a pill I think I'll go by myself."

"Don't leave me."

"Why not?"

Louise hesitated. She loathed asking her younger sister to help her because she knew she'd have to pay her back somewhere, sometime, and it would be when she least wanted to return a favor.

"Oh." Julia tried to conceal her delight as she spied the white heavy ladder behind the forsythia bushes, a rash of blinding yellow. "Gee, Sis, how awful." She started walking away.

"Julia, Julia, don't you leave me up here!"

"Why not? I can't even crack a joke around you but what it gets turned into a spiritual moment by Runnymede's only living saint. Oh, let me amend that, by the great state of Maryland's only living saint."

"What about Pennsylvania?"

"We don't live in Pennsylvania."

"Half of Runnymede is over the line."

"You mean over the top, don't you?" Julia crossed her arms over her chest.

"You know what I mean." Irritation crept into Louise's well-modulated soprano.

"Pennsylvania is so much bigger than Maryland, kind of like a tarantula compared to a ladybug. I'm sure there are lots of living saints in Pennsylvania, probably in Philadelphia and Pittsburgh, but then again—"

Louise cut her off. She knew when Juts was heating up for one of her rambles. "Will you please put the ladder up?"

"No. Mary and Maizie will be home from school in two hours. They can put it up."

Louise's younger daughter, named after Julia Ellen, had been given the nickname Maizie to distinguish her from her aunt.

"Now listen, Juts, this isn't funny. I'm stuck and those noisy kids might not hear me when they get home. Put the ladder up."

"What do I get out of it?"

"Maybe you should ask what you don't get out of it." As Louise edged toward the roofline, little bits of asphalt sparkles skidded out under her heels.

"Bet it's getting hot up there."

"A tad."

"What are you offering me?"

"No more lectures on your smoking or drinking."

"I hardly drink at all," Julia snapped. "I am so sick of you claiming that I drink too much."

"I have yet to see a Saturday night that you don't fill with whiskey sours."

"One night out of seven—it's Saturday night, Louise, and I like to go out with my husband."

"You'd go out whether he was here or not."

"What's that supposed to mean?"

"It means you can't live without male attention and if I were your husband I wouldn't let you out of my sight."

"Well, you're not my husband." Julia dragged out the heavy ladder but didn't prop it against the gutter of the roof. "How come your nose is out of joint, anyway?"

"Isn't."

"Is."

"Isn't."

"Liar."