Excerpt

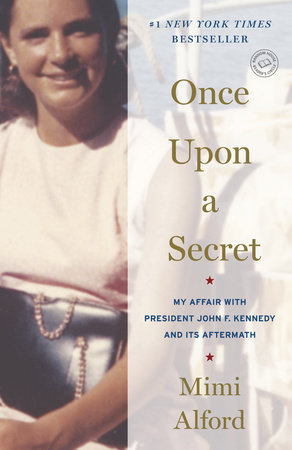

Once Upon a Secret

Chapter One

Everyone has a secret. This is mine.

In the summer of 1962, I was nineteen years old, working as an intern in the White House press office. During that summer, and for the next year and a half, until his tragic death in November 1963, I had an intimate, prolonged relationship with President John F. Kennedy.

I kept this secret with near-religious discipline for more than forty years, confiding only in a handful of people, including my first husband. I never told my parents, or my children. I assumed it would stay my secret until I died.

It didn’t.

In May 2003, the historian Robert Dallek published An Unfinished Life: John F. Kennedy 1917–1963. Buried in one paragraph, on page 476, was a passage from an eighteen-page oral history that had been conducted in 1964 by a former White House aide named Barbara Gamarekian. The oral history had been recently released along with other long-sealed documents at the JFK Presidential Library in Boston, and Dallek had seized upon a particularly juicy tidbit. Here’s what it said:

Kennedy’s womanizing had, of course, always been a form of amusement, but it now gave him a release from unprecedented daily tensions. Kennedy had affairs with several women, including Pamela Turnure, Jackie’s press secretary; Mary Pinchot Meyer, Ben Bradlee’s sister-in-law; two White House secretaries playfully dubbed Fiddle and Faddle; Judith Campbell Exner, whose connections to mob figures like Sam Giancana made her the object of FBI scrutiny; and a “tall, slender, beautiful” nineteen-year-old college sophomore and White House intern, who worked in the press office during two summers. (She “had no skills,” a member of the press staff recalled. “She couldn’t type.”)

I wasn’t aware of Dallek’s book when it came out. JFK biographies, of course, are a robust cottage industry in publishing, and one or two new books appear every year, make a splash, and then vanish. I tried my best not to pay attention. I refused to buy any of them, but that didn’t mean I wouldn’t occasionally drop into bookstores in Manhattan, where I lived, to read snippets that covered the years I was in the White House. Part of me was fascinated because I had been there, and it was fun to relive that part of my life. Another part of me was anxious to know if my secret was still safe.

The publication of Dallek’s book may have been off my radar, but the media was definitely paying attention. The Monica Lewinsky scandal, which had nearly brought down the Clinton Administration five years earlier, had stoked the public’s interest for salacious details about the sex lives of our leaders, and Dallek’s mention of an unnamed “White House intern” lit a fire at the New York Daily News. This was apparently a Big Story. A special reporting team was quickly assembled to identify and locate the mystery woman.

On the evening of May 12, I was walking past my neighborhood newsstand in Manhattan when I noticed that the front page of the Daily News featured a full-page photograph of President Kennedy. I was already late to yoga class, so I didn’t pay much attention to the headline, which was partially obscured in the stack of papers, anyway. Or maybe I didn’t want to see it. I was well aware that tabloids such as the Daily News tended to focus on all things personal and scandalous about JFK. Such stories always made me queasy. They reminded me that I was not that special where President Kennedy and women were concerned, that there were always others. So I hurried past, pushing the image of JFK out of my mind. Keeping a secret for forty-one years forces you to deny aspects of your own life. It requires you to cordon off painful, inconvenient facts—and quarantine them. By this point, I had learned how to do that very well.

What I missed, in my rush to get to yoga, was the full headline below the photo: “JFK Had a Monica: Historian Says Kennedy Carried on with White House Intern, 19.” Inside was a story, taking off from what was in Dallek’s book and featuring a new interview with Barbara Gamarekian, who said she could remember only the nineteen-year-old mystery intern’s first name but refused to reveal it. Her refusal, of course, only incited the Daily News team to dig deeper.

The next morning, at nine o’clock, I arrived at my office at the Fifth Avenue Presbyterian Church, as usual. I hung up my coat, as usual. I took my first sip of coffee from C’est Bon café, as usual. And then I sat down and checked my email. A friend had sent me a message that contained a link to a Daily News story. I clicked on it, not knowing what it was. Up came a story with the headline “Fun and Games with Mimi in the White House.” He had sent it to me, he said, because of the “funny coincidence” of our names.

For the first time in my life, I knew what people meant when they said they had the wind knocked out of them. I went cold. I quickly closed my door and scanned the article. Though my last name at the time—Fahnestock—was not mentioned, I felt a peculiar sense of dread, that everything was about to change. This was the moment I had feared my entire adult life.

I tried not to panic. I took a deep breath and mentally checked off all the things that weren’t in the article. The Daily News didn’t know where I lived. They hadn’t contacted any of my friends. They hadn’t reached out to people from my White House days. They didn’t have my picture. If they had known any more about me they would have included it, right? And they certainly would have tracked me down for a comment.

None of that had happened.

Besides, I had lived through close calls before. A year earlier, the author Sally Bedell Smith had called me at home. She said she was doing a book about how women were treated in the sixties in Washington. It sounded innocent, but it was enough to put me on full alert, and I suspected a somewhat different agenda. I wasn’t ready to start peeling away the layers of secrecy and denial yet, certainly not with a woman I’d never met. I said I couldn’t answer her questions and politely asked her not to call me again, and she honored my request. My secret was safe.

But this Daily News story felt different.

The day after it ran, I arrived at work to find a woman sitting outside my office. She introduced herself as Celeste Katz, a reporter from the Daily News, and she wanted confirmation that I was the Mimi in the previous day’s story.

There was nowhere to hide, and no point in denying it. “Yes, I am,” I said.

“Mimi Breaks Her Silence,” read the headline the next morning.

At this point in my life, I was sixty years old and divorced, living quietly, by myself, in an Upper East Side apartment a few blocks from Central Park. In the early nineties, four decades after dropping out of college, I’d gone back and earned my bachelor’s degree at the age of fifty-one. I was a lifelong athlete and a devoted marathoner who spent many predawn hours circling the Central Park reservoir, and enjoying the solitude. My ex-husband, with whom I’d had a stormy divorce, had died in 1993. My two daughters were grown and married, with children of their own. For the first time in many years, I was feeling a measure of peace.

I had spent time in therapy getting to this place, getting to know myself. After being mostly a stay-at-home mom, I had come to take a great deal of pride in my work at the church. I’d worked there for five years, first as the coordinator of the audio ministry (recording and producing the extraordinary sermons of Dr. Thomas K. Tewell, our senior pastor) and then as the manager of the church’s website. The audiotapes I produced had grown into a significant source of the church’s funding—and the work itself provided not just income but routine and solace. I am not a religious person, but I am a spiritual one, and I loved my work at the church. I also loved my privacy.

When the news broke, it broke everywhere—not only in New York but across the United States and in Europe, too. Here, unfortunately, was my fifteen minutes of fame. The headlines ran the gamut, from predictable to salacious to silly: “From Monica to Mimi.” “Mimi: Only God Knows the Heart.” “JFK and the Church Lady!” I was mocked by one of my favorite writers, Nora Ephron, on the op-ed page of The New York Times. Interview requests poured in, my answering machine full of messages from Katie Couric, Larry King, Diane Sawyer, and, of course, the National Enquirer, which actually slipped an envelope of twenty-dollar bills under my apartment door (which I gave to the church). Weekly magazines deluged me with letters. “Dear Ms. Fahnestock,” they all began, “I apologize for the intrusion. I know this isn’t an easy time for you, but …”—and then they got to the point. A Hollywood producer sent flowers before writing about acquiring the film rights to my story; he offered a million dollars in writing before meeting me. Literary agents descended, wanting to represent me. Edward Klein, author of not one but two scurrilous books about the Kennedys, called to say that if I let him ghostwrite my book I’d be rich and would “be able to live in peace.” Emails arrived from friends, well-wishers, celebrity stalkers, and critics. A college acquaintance provided some comfort: “Please remember that all of this is ‘this week’s news,’ ” she wrote. “It will go away. It’s just that JFK is like Elvis. We all think that we know him and we always want to hear more.”