Excerpt

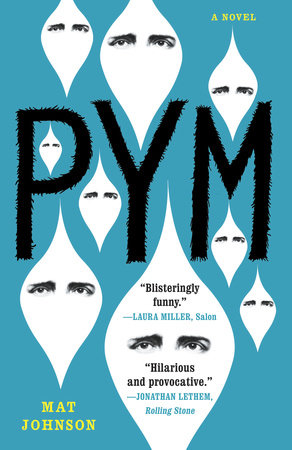

Pym: A Novel

chapter I

Always thought if I didn’t get tenure I would shoot myself or strap a bomb to my chest and walk into the faculty cafeteria, but when it happened I just got bourbon drunk and cried a lot and rolled into a ball on my office floor. A couple days of this and I couldn’t take it so I ended classes a week early and checked into the Akwaaba Bed and Breakfast in Harlem to be among my own race and party away the pain. But mostly I just found myself back in that same ball some more, still on the floor, just at a more historically resonant address. My buddy Garth Frierson, he’d been laid off about six months before, and was nice enough to drive all the way from Detroit to help a childhood friend. This help mostly consisted of him sitting his bus driver ass on my rented bed, busting on me until I had enough shame to get off my own duff and try to make something of myself again.

By then the term was over, graduation done, campus vacant. I didn’t want to see anybody. The only things worse than the ones who were happy about my dismissal were the ones that weren’t. The sympathy, the condolences. It was all so white. I was the only black male professor on campus. Professor of African American Literature. Professional Negro. Over the years since my original hire I pushed away from that and insisted on teaching American literature in general, following a path toward my passion, toward Edgar Allan Poe. Specifically, I offered the course “Dancing with the Darkies: Whiteness in the Literary Mind” twice a year, regardless of enrollment. In regard to the number of students who chose to attend the seminar, I must say in my defense that the greatest ideas are often presented to empty chairs. However, a different theory on proper class size was cited in my denial letter from the president, and given as a reason to overturn the faculty’s approval.

Curing America’s racial pathology couldn’t be done with good intentions or presidential elections. Like all diseases, it had to be analyzed at a microscopic level. What I discovered during my studies in Poe’s and other early Americans’ texts was the intellectual source of racial Whiteness. Here, in these pages, was the very fossil record of how this odd and illogical sickness formed. Here was the twisted mythic underpinnings of modern racial thought that could never before be dismantled because we were standing on them. You don’t cure an illness by ignoring it or just fighting the symptoms. A Kleenex has never eradicated a cold. I was doing essential work, work affecting domestic policy, foreign policy, the entire social fabric of the most powerful nation of the world. Work that related directly to the way we lived our daily lives and perceived reality itself. Who cared if a bunch of overprivileged nineteen-year-olds with questionable hygiene could be bothered to rise for the 8 a.m. class? Who cared if I chose to not waste even more precious research time attending the toothless Diversity Committee?

“Just get your books, dog. And get out of there. Pack up your place, focus on what you can do. You want, you can come back with me to Detroit. It’s cheap, I got a big crib. Ain’t no jobs, but still.” Garth and I drove up the Taconic in the rain. I was still drunk, and the wet road was like lines on a snake’s back and my stomach was going to spill. Even drunk, I knew any escape plan that involved going to Detroit, Michigan, was a harbinger of doom. Garth Frierson was my boy, from when we were boys, from when I lived in a basement apartment in Philly and he lived over the laundromat next door. Garth didn’t even ask how many books I had, but he must have suspected.

Because I had books. I had books like a lit professor has books. And then I had more books, finer books. First editions. Rare prints. Copies signed by hands long dead. Angela walked out on me a long time ago and my chance of children walked with her, but I had multiplied in my own way. I’d had shelves built in my office for these books, shelves ten feet tall and completely lining the drywall.

The campus was dead. A vacant compound hidden from the road by darkness and hulking pines. The gravel parking lot was empty, but I made Garth park in the spot that said president—?violators will be towed on principle. When you get denied tenure at a college like this—intimate, good but not great—your career is over. A decade of job preparation, and no one else will hire you. If you haven’t published enough, people assume tenure denial means you never will. If you have published and were still denied, people assume you’re an asshole. Nobody wants to give a job for life to an asshole. And they didn’t have to in this economy. Outside of a miracle, after denial I would be lucky to scrounge up adjunct teaching at a community college somewhere cold, barren, and far from the ocean. A life of little health insurance, bill collector calls, and classrooms with metal detectors, all compliments of this college president, Mr. Bowtie. The least I could do was shit in his space for an hour.

We trudged. The building looked like an old church that had lost its faith, every step up the stairs a sacrilege. Garth huffed, but followed. I’d chosen an office in the back of the top floor to dissuade students, but my lectures had done a better job of this. My office was a narrow A-framed cathedral with a matching window. A shrine to the books that lined the walls and my own solitude.

“Bro, I’m not going to lie to you. I got a lot of books in here,” I said, letting him in first.

“You do?” Garth asked me. Because I didn’t.

It was empty. I should have been greeted with the hundreds of colored spines of literary loves, but there was nothing. My books were gone. My office had been cleared out. Everything was gone: my pictures, my lamp, my Persian rug, everything not school property or nailed down, gone. A chasm of vacant whitewashed bookshelves opened up before me.

I was breathless. Garth was out of breath, but for him, it was just all the stairs.

“They took my shit, man. They took my shit,” I kept repeating. I walked over to the desk and pulled out all the drawers. There were some chewed yellow pencils left, and a few folded Post-its and bent paper clips, but that’s not what I was looking for. I kept searching, desperate, sliding pencils and papers around, looking for more.

“Damn, dog. You didn’t have no porn in there, did you?” Garth already had his Little Debbie out and was chewing on it like it was his reward for making it up three floors of nineteenth-century stairs.

“Just a picture,” I told him.

“A picture of what?”

“Angela,” I admitted.

“Worse,” Garth said, head wagging.

I slammed the drawer shut, and it was loud. And I liked that sound, a moment of violence, but this time coming from me. So then I started banging on the empty shelves with my fists, and they vibrated. You could hear the echo in the room, then bouncing off into the empty building beyond us until Garth closed the door.

“That’s wrong, man. Disrespectful. Forget them, job’s over. That’s life, what you going to do?”

I was going to show up at the president’s house and kick his ass, it occurred to me. This act suddenly seemed like the only thing worth running away to Detroit for. I didn’t tell Garth this, because he would have stopped me. He was big enough to fill up the door. He was even bigger since he’d been laid off. I remembered when this man was skinny, ran track. Ran it poorly, but still. It was depressing looking at every extra pound on him, each a reminder that we were both moving swiftly into decline with little else as accomplishment.

“Wait in the car, man. I just have to check my mail,” I told him. Garth did it. I’m a bad liar, but he was tired and it was really cold outside, and brothers don’t like the cold.* It was late spring, but it had been raining for a week and upstate New York was frigid in a way which was more gothic and empiric than the Philly chill we’d grown up with.

#“You drunk. I’m tired as all hell. The sooner you get your ass out of here, the sooner you get to get your ass out of here,” Garth offered, but he left. So then I walked over to the president’s house to punch him and maybe kick him a few times too.

In my head, I was getting “gangsta,” which I’ve always felt showed greater intent than getting “gangster” in that it expresses a willful unlawfulness even upon its own linguistic representation. I was going to show him how we do where I’m from, go straight Philly on him, and I knew all about that because, although I had never actually punched someone in the face before, as a child I myself had been on the receiving end of that act several times and was a quick study.

The president’s house was at the other end of the campus, but it was a small liberal arts campus. An empty space, dorms and buildings deserted, solar streetlamps popping on and off for just me. While I was walking, stoking my anger, thinking of all the work I’d done and all that security I was now being denied, I came

* Matthew Henson excluded.

to the administration building, and I saw that there was a light on. Downstairs, in the back, in the president’s office. No one just left interior lights on, the environmental footprint too massive, the cost too high, and with every attack the prices went even higher. So he was in there. The outside door opened, and I knew he was in there.

And then there was this overwhelming emotion. It was not rage or anger. It was something even more illicit, unwanted. It was hope. Here we were, two men alone. Society vacated, and now just two men and a problem, one that somehow in my stupor seemed workable. There was a guy down the hall, a Romanticist, who had been denied tenure ten years ago. Approved by the faculty committee, just as I was, only to be shot down by the same president in the same manner. And he had, in his grief, approached the all-powerful boss man, and he had repented all of his sins, real and imagined, and was granted a permanent teaching gig. It made sense too, for as Frederick Douglass’s narrative tells us, it is more valuable to a master to have a morally broken slave than to have a confident one. That Romanticist’s story had always seemed humiliating to me before this moment, but suddenly it became inspirational. At the president’s door, I paused, prepared myself for what could be simply the final test before I overcame my troubles. I took a deep breath to prepare for a performance of dignified groveling. Then I heard the music coming from inside.

What I saw scared me. Took me out of my confidence, my momentum. What do you make of a Jew sitting in the dark listening to Wagner in this day and age? I could think of no more call to the end of the world than the one I was looking at. Random violence on the news had become background noise to me at that point, but this scene genuinely scared my ass. Still in his bow tie and tweed jacket at this time of night, it was disgusting. He hit his keyboard quickly, and suddenly the sound became Mahler, but I knew, I knew what I’d heard. As the sound cleansed the room, the bald man just looked at me, drink in hand. As drunk as I was, I could still smell the sweet singe of alcohol hanging in the air.

“My shit!” it came out. It lacked the eloquence of a planned rebuttal, but he understood.

“Packed by movers, delivered to your listed residence. A thank-you, really, for your service. Thank you.” He said the last bit as if I should be saying this to him, but still it robbed me of a bit of my momentum. I had been surviving on righteous indignation and self-pity for weeks, I realized once the supply seemed threatened. But then I remembered I’d been canned and my fuel line kicked in once more.