Excerpt

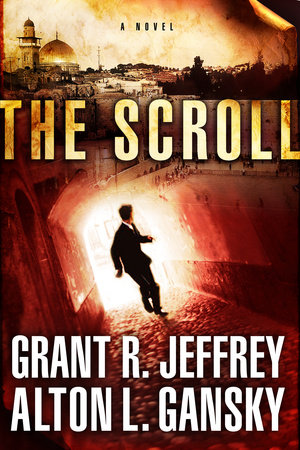

The Scroll

Cambridge, Massachusetts, March 30, 2013

It was a good wall, a wall anyone would be proud of. Situated in such a way that someone entering the condominium would see the items hanging on its pale blue surface before noticing the rest of Dr. David Chambers’s large, sixth-floor residence overlooking the Charles River in the south part of Cambridge. The condo was close enough to Harvard to make commuting tolerable, and just far enough away for Chambers to feel free of the world’s most prestigious university.

The condo was well above his professor’s pay grade, but his last two books had done well enough for him to be free of money concerns.

Beneath Hostile Sands sat at number six on the

New York Times nonfiction best-seller list. It had been nine months since the announced discovery of Herod’s tunnel. His publishers pressed him to include it as the final chapter in the book, then rushed to press. Then came the countless interviews. The academic papers he penned caused a furor in the tight-knit community of archaeologists, a community that never felt more alive than when being critical of one of its own. No one raised an accusing finger at his discovery. They couldn’t. His scholarship was beyond criticism.

Chambers stood before the wall and gazed at the items hanging there. Together they summarized a twelve-year history of his spotless career. Someone in the Harvard PR department dubbed him the most interviewed scientist in the world. That was probably true. Society could only tolerate a few scientific golden boys. The astronomer Carl Sagan had taken the art of popularizing science to rare heights. Others followed: the physicist Michio Kaku, astrophysicist Neil deGrasse Tyson, and others were frequent guests on talk shows. The public had a hunger for news from the world of science— news most couldn’t understand. The contemporary faces of science were those rare individuals who knew how to talk to the camera and do so in plain language. It was something at which Chambers excelled.

Chambers set a cardboard box on a narrow, art deco–style table. All the furniture in his condo centered on the 1920s style. Someone once asked why he chose art deco. He had no answer. His interior designer had suggested it, and it sounded good to him. He was a smart man, more intelligent and insightful than most, but he excelled in only a few things. In everything else, he was blissfully dense. Perhaps if his range of interests had been wider, perhaps if he had honed his other instincts to the same edge as those that guided his career, he wouldn’t be doing this today.

He eyed the plaques, photos, and framed articles hanging against the smooth surface. He took the closest in hand and lifted it from its hanger. Like all its companions, the object had been professionally framed. Inside a silver frame rested the cover of his latest book. Chambers waited for a sense of pride to wash over him, but it never came. He put the frame in the cardboard box.

Next he pulled down the framed cover of

The Fingerprints of God, his first book. That work had been far more religious in nature as he guided the reader through the greatest discoveries in biblical archaeology. To Chambers, however, it was also a scholarly nod to William Foxwell Albright, the founder of the biblical archaeology movement. It had been Dr. Albright’s book

The Biblical Period from Abraham to Ezra that had birthed his interest in archaeology; that and the work of his father.

The thought of his dad soured Chambers’s stomach. Those who knew Chambers knew of his father and assumed Chambers had chosen to follow in his old man’s footsteps. Chambers never corrected the impression, nor did he encourage it. The only thing his father did to kindle the archaeological spark in his son was leave Albright’s book on the shelf. Chambers found it, and it set the course of his life.

Dr. Albright died in September 1971, two years before Chambers’s birth. That didn’t matter. Time meant less to an archaeologist than to others.

Albright, while hailed among biblical scholars, was not as orthodox as most thought. He believed the religion of the Israelites moved from polytheism to monotheism, an idea rejected by conservative Bible scholars. Chambers had wanted to honor Albright while correcting his “more liberal” interpretations.

The last thought amused him: how far he had come. Perhaps bemused was a better term. If Albright were alive today, he’d take Chambers to task for his newfound disbelief.

He set the framed cover in the box and followed that with plaques, awards, and articles about himself carried in

Newsweek, Time, Biblical Archaeology Review, and a dozen other such publications. He removed photos taken of him with Larry King, John Anderson, Ted Koppel, and Jay Leno. He had other such publicity photos that never made it to the wall.

He paused before removing the last photograph. He studied it. The time: two years ago; the place: outside Tel Aviv; the woman: his fiancée.

His former fiancée. Amber wore jeans, a dirt-caked, formerly white T-shirt, and a pair of gloves that seemed a size too large for her petite hands. The sun shone on her brown hair and sparkled in her blue eyes. The David Chambers in the photo smiled as well. In fact, he beamed. No man had better reasons to smile.

That smile would disappear a month later.

He snatched the photo from the wall and tossed it into the box. He heard glass break. He didn’t bother to look at the damage. He opened the single drawer in the table and removed a well-worn book. He pushed back the black leather cover and saw an inscription bearing his name. Gently, he touched his mother’s signature, then his eyes fell to his father’s scribbling.

Chambers pursed his lips and threw the Bible in the box. Moments later, he sealed the box with packing tape and buried it in his closet: a cardboard ossuary holding the bones of his past.

He closed the closet door on his history and turned to face his future.

Dr. David Chambers sat in his new ergonomic office chair with his feet on the wide mahogany desk. By executive standards, the office was small, but it was still larger than the closets most professors were forced to use. Chambers was still young, so he would have to wait for older profs to retire or die before he could expect more elbow room. Unlike his home, the office was Spartan. A bookshelf lined one wall and needed dusting. Stacks of journals, scholarly white papers, and files stood precariously on the floor. One of his students, perhaps trying to impress his teacher, said, “It looks like the salt pillars along the Dead Sea.” Chambers had laughed and pointed to the tallest pile. “That’s Lot’s wife.” It was the kind of joke that only archaeologists would appreciate.

His eyes scanned a scientific journal that reported on grants given for scientific exploration. Any that mentioned Israel or Palestine he skipped. He was done with that phase of his studies but had yet to settle on a new discipline. His interest in biblical fieldwork had departed with his faith.

He had a friend who worked in pre-Columbian archaeology, specializing in the mysterious Olmecs in the lowlands of south-central Mexico. The people group flourished from 1500 BCE to roughly 400 BCE, a time period with which Chambers was familiar. Still, his academic focus had been on the other side of the world. He had deep doubts about his ability to raise money to fund a dig in an area about which he had never written; hence the need for a friend with a credible reputation in ancient pre-Columbian history.

Perhaps he could call in a few favors and sign on as dig director, share a byline or two on some academic papers, and then fund his own dig. All that might take as little as five years—if he were lucky.

He decided to make the call. After all, any civilizations that sculpted three-meter-high human heads deserved a little attention. The recent attention and media coverage of all things related to the Mayan culture and calendar were certain to raise interest in Central American archaeology.

He reached for the phone. As he touched the hand piece, it rang.

“Yeow.” Chambers snapped his hand back, then chuckled. “What are the odds…” He answered. “David Chambers.”

“

Shalom, Dr. Chambers.”

Chambers had no trouble recognizing the voice of his old friend Abram Ben-Judah.

Maintaining a running inside joke, Chambers answered Ben-Judah’s Hebrew greeting with the Greek word for peace. “Eirene.” Old Testament versus New Testament.

“It has been much too long since last we talked, my friend.”

The image of Ben-Judah flashed in Chambers’s mind: tall, slightly stooped, white-and-black beard, kind gray-blue eyes, and a face that looked a decade older than his seventy-plus years. “It has, Abram, it has. How is little Miriam?”

“My granddaughter is well and not so little anymore. She turns thirteen next month.”

“In my country, that’s the age fathers begin loading their shotguns.”

“Shotguns?”

“To keep the boys away.”

“Ah.” Ben-Judah laughed, but Chambers recognized a courtesy chuckle when he heard one.