Excerpt

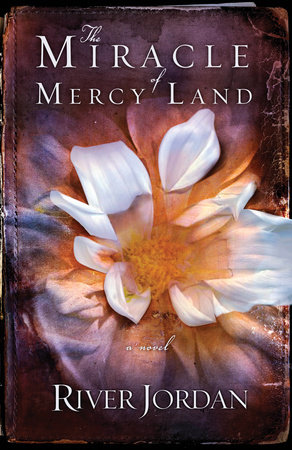

The Miracle of Mercy Land

ONE I was born in a bolt of lightning on the banks of Bittersweet Creek. Mama said it was a prophecy, and as she is given to having visions of the biblical kind, no one argues with her. She can match what she sees with ancient words, and truth be told, she is frightening with the speaking of them. Mama can swipe you with her eyes so that you feel like you have either been hushed or resurrected by God’s own hand.

On the fateful day of my birth, there had been no signs, natural or otherwise, that foretold what the day would bring. No wild birds roosting in the trees, no funny-yolked eggs, no hints to suggest that a baby was about to show up in a stormy kind of way. The only visible condition at all had been Mama’s fat feet. They were so swollen by that time that they were no longer like feet at all. That’s what drove her down to the creek bed, searching out an herb known for helping such as this. She had on Daddy’s big boots on account of the fact that not a single pair of her own would fit over her feet, and she had just managed to get down to the water’s edge when the first thing happened: the storm came up. The second was I showed up, just as quick and sudden as the wild wind.

Mama tried to call for Ida, but her cries were snuffed by the rolling thunder. So there she was with bolts of lightning crashing all around, hitting the water—she told me she could feel that electricity run through her body, that it was like fire coming from the sky—then she cried out for mercy. That’s how me and Mama came to have a private moment suspended in the crook of the bank. By the time Aunt Ida found us, the storm had passed, the clouds had given way, and the blue sky hovered above her like an eagle’s eye. Mama said she took one look at me and said the only

name that came to mind. “Mercy,” she whispered to me. I answered her with a wailing cry.

Bittersweet is a knotty gathering of simple people who live along the riverbank. The entire place is no more than a boot stomp. It has no official standing as a town at all. It is simply called that by the people who have built their lives along those banks. Had I stayed there, rocking on Aunt Ida’s front porch, watching the water rise and fall, fearing the floods and staying on in spite of them, I wouldn’t be in the middle of where I am now: Bay City. Well, they call it a city, such as it is. But it is nothing more, really, than a beautiful little town rolled out right around the warm, gulf water bay of southern Alabama. It is a city of refuge, bright with possibilities. Everyone who has ever crossed into this place feels that way right down to their toes. When you visit, it will make you believe that it is a place where you can live in fruitful fullness. All

sugar, no spice. Or at least that was what it was like when I arrived.

But that was seven years ago. Everything was more peaceful then, but now, it seemed that the whole world was on the verge of war. President Roosevelt said we were staying out of it, but the dark things that were happening overseas tugged at our ankles like a small, nipping dog. The world would not go away no matter how much we tried to shake it off. The events that lay before us as a nation were a large, uncharted territory, watery in their shifting possibilities. The only thing certain was that the future would have to reveal itself in due time, and most likely it would be different from anything we had expected. In the meantime we went through our daily routine with a type of laughter we hoped would stave off impending enemies and allow our sacred routines to remain a part of our carefully plotted lives. For the moment the edges of our existence played out sweetly, simply, and untouched by the things we knew were happening beyond the borders of our existence. There was a whole ocean between us and the trouble. It seemed like an ocean should be enough.

Maybe that’s why, in the midst of our time of innocence and uncertainty, the very thing that happened to me was the most wildly unexpected: the mysterious wonder of something that I will attempt to understand fully for the rest of my days. I should make a feeble effort at explaining what took place. My words might be nothing more than a ripple across the waters of time, but they are surely better than no record at all. It began last winter along the Alabama shores. And it was all because of Doc. That’s where the business started.

Doc Philips owned the

Banner, and owning Bay City’s only paper was better than being mayor. It was better than being anybody else in town. People trusted Doc with the most important thing of all—the truth.

The second best thing to owning the paper is what I did. I was Doc’s assistant, and that meant I was really the assistant editor. To his credit, Doc tried to give me that title, but it didn’t stick because people just called me Doc’s girl. That’s what they’d say ’cause it made it easy on them. No official title would tarry. They made up their own. Doc’s girl. I didn’t mind.

The

Banner was my life, and I loved everything about it. It was a pinch-me-quick-I’m-dreaming kind of situation: the smell of the ink from the printer downstairs. I could probably typeset the whole thing, but that’s Herman’s job, though I’ve helped him in a rush, put on an apron, and hit the presses with him showing me the ropes. I know the smell and sound of every corner of the

Banner. The ticker machines clicking off the news by the minute, going to sleep when nothing in the world is happening but then coming alive all at once when the wires are just burning up with stories. That’s my favorite part of the job: getting the skinny on what’s happening around the world before most folks have even had their morning coffee.

Sometimes we ran the stories just the way they were, straight off the wire, but other times Doc decided to give them a little local flavor. He’d tie in DiMaggio’s home run with what one of the local boys did Saturday down at the park. That’s the way he was— “bringing it home,” he called it. “Let’s just remember, Mercy,” he’d tell me. “The news doesn’t mean a thing at all unless we’re bringing it home.”

I always said, “You got it, Doc. Sure thing.” But I didn’t get a huge chance to bring the big news home. That was Doc’s job. I wrote up the smaller stories that happened around Bay City, like all the events of people’s lives that must be made public. Births and deaths, marriages and other procurements. Doc covered the real news—any criminal cases, bank robberies, and kidnappings. Since we hadn’t had any of those, he mostly reported on things like the new traffic light going in and the worldwide news from the wire.

But that was before Doc’s big secret showed up in town. It’s not that I loved the paper less; neither did Doc. How could we? It was the heart of Bay City and the pulse of the world. But then something just appeared—from another world or time or, well, let’s just say, it sure wasn’t from around here. To say it became a distraction would be a flat-out lie. It became an

obsession.Doc swore me to complete secrecy so that no one in town knew a thing. But that wasn’t the toughest part; he swore me to keep the secret even from everyone in Bittersweet Creek. All of them thought I was going about my regular life, taking care of business and printing the news. They were completely wrong. The greatest story in the entire world had fallen right into my hands, and I couldn’t print a word of it.