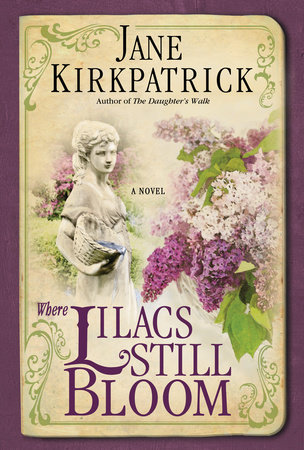

Excerpt

Where Lilacs Still Bloom

Prologue

1948

It’s the lilacs I’m worried over. My Favorite and Delia and City of Kalama, and so many more; my as yet unnamed

double creamy-white with its many petals is especially vulnerable.

I can’t find the seeds I set aside for it, lost in the rush to move out of the rivers’ way, get above Woodland’s lowlands

now underwater. So much water from the double deluge of he Columbia and the Lewis. Oh, how those rivers can rise in

the night, breaching dikes we mere mortals put up hoping to stem the rush of what is as natural as air: water seeping, rising, pushing, reshaping all within its path.

I watch as all the shaping of my eighty-five years washes away.

My only surviving daughter puts her arm around my shoulder, pulls me to her. Her house is down there too, water

rising in her basement. We can’t see it from this bluff.

“It’ll be all right, Grandma. We’re all safe. You can decide later what to do about your flowers,” my grandson Roland

tells me.

“I know it. All we can do now is watch the rivers and pray no one dies.”

How I wish Frank stood beside me. We’d stake each other up as we did through the years. I could begin again with him at my side. But now uncertainty curls against my old spine, and I wonder if my lilacs have bloomed their last

time.

One

Food for Thought

Hulda, 1889

Daffodils as yellow as the sun, ruby tulips, and a row of purple lilacs from the old country border the house I live

in with my husband, Frank, our three young children (ages eight, five, and three), and next month, if all goes well, our

fourth child. We are hoping for a boy. My parents live with us, but only for a few more months. They’ve built a new house near Woodland, Washington. We’ll be moving too, to a farm of our own south of Whelan Road. We’ll still be within a few miles of each other, a close-knit family of German Americans captured by this lush landscape between the Lewis and Columbia Rivers. We call where we live the Bottoms. It’s made up of black soil that was once the bottom of those great rivers—and sometimes becomes so again with the floods. We hope our new places will be less prone to flooding, though it’s the nature of rivers to rise with the spring thaws. We live with it.

My mother and children have dug daffodil and dahlia bulbs, snipped lilac starts to plant, and my sisters and brother

and neighbors will give us sprouts from their bushes once we move, which is the custom. A lilac says “Here is a place to stay,” and how perfect that such promise of permanence should come from family and friends?

We can’t move the apple orchard. But I wielded my grafting knife and wrapped the shoots, scions they’re called, in

sawdust and stored them in the barn earlier this year when the trees were dormant. Today I’ll graft them onto saplings at my parents’ new house, so one day there’ll be an apple orchard there. I’ve also stepped into the uncommon for a simple house Frau: I’ve grafted a Wild Bismarck apple variety known for its crispness with a Wolf River, an apple of a larger size.

My father encouraged such dappling with nature—and that I keep my efforts quiet, at least for a time.

It was April, and we tied the scions onto the saplings he’d started as soon as he knew they’d be building the house. I

liked working with my father in the orchard, a misty rain giving way to sunbreaks, and the aroma of cedar and pine

drifting down from the surrounding hills in the shadow of Mount St. Helens. So much seems possible in such vibrant

landscapes. A garden is the edge of possibility.

He was a great storyteller and advice giver, my father, though this day his story surprised. “Don’t tell Frank right away,” he told me. “Let him think you’re just grafting plain old apples to help us extend the orchard.”

“Frank wouldn’t mind.”

“In time—when you have the final result in hand. But Frank discourages you. I see it, Hulda.” I pushed at my frizzy

walnut-brown hair and stared at him. “He dismisses your interests if they go beyond your children and him.”

“It’s a woman’s duty to meet her family’s needs.”

“Meet their needs first. But you want a crisper, bigger apple too,” he said. “Nothing wrong with that.”

“I do. I get so annoyed at those mealy things that hang on to their peels like bark to a tree.”

He nodded. “Some would say that meddling with nature isn’t wise. Frank might agree—especially if the one meddling

is a mother who should be content with looking after her family.”

I stood, using my hoe to help me and my burgeoning belly up. I was nearly as tall as my father. He liked Frank; at

least I always thought he did. My love and admiration for both men were rooted deep. It felt strange to defend my husband to my father. “You’re wrong, Papa.” I pushed my pointy straw hat back. “Frank’s a good helpmate for me. And he’ll like having more pies.”

My father tied another scion onto a branch, making sure the cambium was fully covered in the slanted cut I’d made so

the two would bond securely. “You have a gift, Hulda. You can see distinctive things in plants. You see the possibility,

like a crisper, larger apple and then imagine it into being.” He lifted another scion as emphasis. “Those are gifts few have, and people can be envious.”

My father had never granted me such a compliment, and I was both pleased that he noticed and humbled that he

shared it. “Not Frank,” I insisted.

“Not everyone understands that we are all created to have complicated challenges and dreams. We must honor our longings, then go beyond them whether others support us or not.”

I wondered if he spoke of my mother. Did she resent my father’s dreams that took us from Germany to Wisconsin,

Minnesota, San Francisco, then back to Wisconsin, and then here to the Lewis River of the new state of Washington? My father had many longings: farming, becoming a brewmaster, investing in creameries and cheese factories before the landscape was dotted with cows. He’d done all those. Now logging interested him, and he’d built a big two-story house; yet another adventure that meant more change for my mother—and the rest of us too.

“My dream is to raise my family.” I didn’t see getting a crisper apple as any budding desire. I wasn’t rising beyond my

station. “These apples will make life better for them.” I was merely an immigrant housewife wanting to save time peeling apples.

“Just think of what I’ve said.” He wrapped his big paw around my hand that was holding a scion. He looked me in

the eye. I swallowed. “Huldie, don’t deny the dreams. They’re a gift given to make your life full. Accept them. Reach for them. We are not here just to endure hard times until we die. We are here to live, to serve, to trust, and to create out of our longings.”

“Yes, Papa,” I said, but it wasn’t until after he was gone, years later, that I came to understand what I’d committed to.