Excerpt

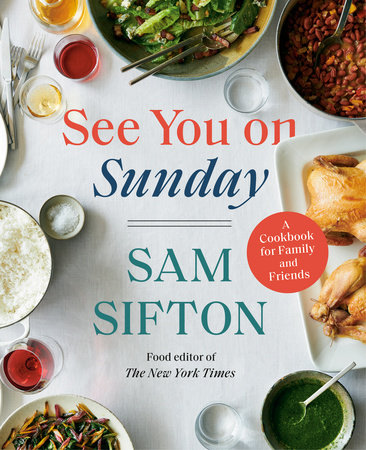

See You on Sunday

Chapter One

A Theory of Dinner

“They broke bread in their homes and ate together with glad and sincere hearts.”

—Acts 2:46

“See you on Sunday.”

The dinners started years ago, in a drafty loft on an empty block in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, with a tiny gas stove and an enormous butcher-block prep table. Later they occurred in a walk-up in Greenpoint, a few miles north along the East River, with tiny babies sleeping in the hall. Big vats of pasta. Roasted chickens. Platters of ribs. Then came epic meals out on Long Island, in a little house steps off Main Street, and quieter ones on the southern coast of Connecticut, in a white kitchen out of a Cheever short story. Clams and corn, vegetables roasted on a sheet pan, ducks braised in a pot, huge briskets, many pizzas, stir-fries, ham, chili, turkey, repeat.

We gathered in Maine to eat off a wood stove, and in Florida to pick at grouper or trout as the sun fell into the Gulf. We cooked on roofs, in yards, in kitchens small and dingy, large and luxe, and beneath fluorescents in a narrow Brooklyn parish-hall galley, to feed groups of twenty, thirty, more. We cooked for family, real and imagined, informally, formally, somewhere between the two. We cooked for friends who were happy or troubled, for people in programs that had them floating a line between the two.

The point was to cook or, more accurate, the point was to gather around a table with family and eat, and to do that regularly enough that people knew it was happening, could depend on it somehow, this consistency in a world that doesn’t offer a lot of that outside of work and pain. Sunday dinner. Sunday supper.

Word got around. And the calls or texts would start coming: “There dinner on Sunday?”

Yes. See you then. Bring wine or a cake, a friend, some flowers, nothing at all.

People are lonely. They want to be a part of something, even when they can’t identify that longing as a need. They show up. Feed them. It isn’t much more complicated than that. The point of Sunday dinner is just to have it. Even if you don’t particularly like entertaining, there is great pleasure to be had in cooking for others, and great pleasure to be taken from the experience of gathering to eat with others. Sunday dinner isn’t a dinner party. It is not entertainment. It is just a fact, like a standing meeting or a regular touch football game in the park. It makes life a little better, almost every time.

There is some science to back up the assertion. We know that children who eat with their families regularly do better in school. They have better vocabularies. They are less likely to develop eating disorders, abuse drugs or alcohol, become teen parents. They have better manners. They have higher self-esteem. Have your kids eat dinner with adults—not just their parents, but friends from work, from the street, from the gas dock or library reading group—and they are likely to learn more about the human condition than children who do no such thing.

A number of years ago I cooked a dinner for a couple dozen people at a church in Brooklyn, a duty I took up a few times a season then: a Sunday dinner to follow a short, late-afternoon service. My children fumed throughout the liturgies of word and table alike, as children do. They saw the time spent in pews as silly and boring, a waste of time they might have better spent reading manga or doing homework.

Perhaps they were right. But also, as they generally did, my children shared dinner with the rest of the congregation after the service, talking with grown-ups from the neighborhood, artists and teachers, seekers and the lost. They drew crayon drawings on the paper tablecloths and played with kids they saw weekly but whose last names they did not know.

My children enjoyed these dinners, though I know they were loath to admit it. They disliked all that preceded them. “Church ought just to be dinner,” one of them said that night. I smiled in response and, if I were a better parent, I might have said that this is already the case, at least in a church that sees its beating heart in the sacrament of the Eucharist: the consumption of bread and wine. But the kids were off clearing the tables by then, and asking for ice cream.

So that was a successful Sunday dinner, in my mind. They ate with others, and appreciated the experience. That’s not nothing. The experiences mount.

Adults benefit from the fellowship of the table as well, as much as and probably more than children. “Life satisfaction” is a term of art used by social scientists to capture a person’s overall happiness and well-being. Life satisfaction, the academics say, is strongly correlated with time spent with those who care about you and about whom you care. Dinner is a marvelous way to create that time, to mark it, to make it happen. The life satisfaction does not come from the first meal, or the fifth or the twentieth, but from the effort itself, from the accrual of experience in cooking the meal and sharing it. Regularity matters. Sunday dinners, at their best, are simply special occasions that are not at all extraordinary. They become that way over time.

See You on Sunday is a book to make those dinners possible. It is intended as a rough guide to the business of preparing meals for groups larger than the average American family, which currently hovers in the neighborhood of three. In general, then, the recipes in the book are all written for yields of around six servings (or four to eight depending on portion size), though they are all easily scaled up to feed a crowd and indeed, in some cases—gumbos, roasts, and others—they are meant expressly to feed a large group.

The recipes are mostly simple, if occasionally labor-intensive. They are largely free, I think, of fanciness. The intention is that you can make them. They derive from decades spent cooking for my family and for groups ranging from six to sixty, and from years spent talking to restaurant chefs and cookbook authors and home cooks in connection with my daily work at

The New York Times, where I have done many things but have always written about food.

The architecture of the book is simple too, or is meant to be: chapters devoted to proteins and grains, to vegetables and dessert, as well as to the joys of exception—taco dinners and pizza parties, meals just for the family, a fine occasion for friends.

Some stipulations about what Sunday dinners mean for the home cook. First: They are not intended to be feasts in the banquet sense of the word. Food costs matter. Veal for a crowd is expensive. So is grouper, so sometimes are duck legs, and a standing rib roast of beef ought to be a rare treat. You are not a feudal landowner entertaining the serfs. You are a member of a family, real or imagined, cooking a meal. So you will see a lot of recipes within this book for cheaper cuts of meat and, along with them, exhortations that you stretch out one-pot meals with gravies and sauces. A vat of something flavorful with a pot of white rice or a tray of roasted potatoes is sometimes all you are after. Simplicity can be more than enough.

“Just throw some stuff in a pot,” the Reverend John Merz said to me once. “Put that on rice. That’s it.” Merz runs our Episcopal parish in Greenpoint, Brooklyn. He was giving me advice before the first meal I ever cooked for his congregants and advising me to keep it simple. I’ve known Merz since childhood, when the last thing that could have happened was that John Merz would become a priest. Which is to say: He didn’t say “stuff.” I’ve kept the advice in mind ever since.

An equally important stipulation, from the point of view of both value and health:

See You on Sunday offers a number of recipes for grains and vegetables that rightly ought to be seen not as side dishes to accompany a main-event protein but as equal, if not greater, players on the dining room stage. The words of Michael Pollan should ring true for Sunday dinners as in the rest of our diet: “Eat food. Not too much. Mostly plants.” That may be difficult to do in the face of fried chicken or roast pork, to be sure. (And these make terrific Sunday dinners.) But it is worth noting all the same.

I came to the belief on my own, with no intention, by accident. I was cooking a Sunday dinner out on Long Island, off the grill. It was high summer, and the farm stands nearby were thick with produce. I roasted Fairy Tale eggplants over the fire, daubed them with goat cheese, and drizzled them with olive oil. I melted onions after that, getting them soft and slightly charred. Squash got a similar treatment, and I hit them with a splash of lemon juice amid the oil. The main event was meant to be smoke-roasted chicken—I had a couple of them, beautiful local birds I’d rubbed in spice. These I put to one side of the old gas grill that had lately come into my possession, and on the other I put a pack of wood chips in a perforated envelope of aluminum foil. Fire went to that side. The chicken side I left unlighted. I put the top down and went into the house to make a pilaf and get some corn going.

But as I say, it was an old grill new to me, with balky qualities I had yet to discover. When I went out to check on the birds, they were incinerated: coal-black husks, burned beyond recognition. I quietly tipped them into the trash, returned to the kitchen, fluffed the rice, and served it with the vegetables: a vegetarian feast. A dozen people did not remark on the loss. I learned a great deal from that night, and not just about gas grills.