Excerpt

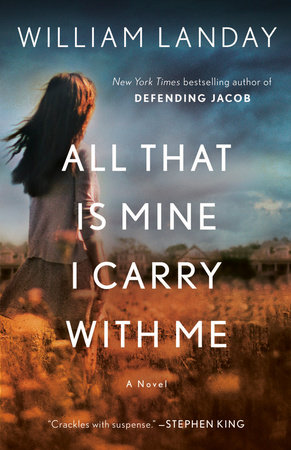

All That Is Mine I Carry With Me

After I finished writing my last novel, I fell into a long silence. You might call it writer’s block, but most writers don’t use that term or even understand it. When a writer goes quiet, nothing is blocking and nothing is being blocked. He is just empty. I don’t know why this silence settled over me. Now that it’s over, I don’t like to think about it. I only know that for months, then a year, then two years, I could not write. It did no good to struggle; the more I struggled, the tighter the noose became. I could not write, then I could not sleep, then I could not bear my own presence and I began to think dark thoughts. I won’t dwell on the details; in my profession, there is a saying that a writer’s troubles are of interest only to other writers. I mention my silent period here only because it is the reason I wrote this book, for it was during this time, when I would have grabbed at any plausible idea for a story, that I got an email from an old friend named Jeff Larkin.

I have known Jeff since we were twelve years old. We met in September 1975 when we entered the seventh grade together at a very august and (to me) terrifying private school for boys, and we became pals almost immediately.

Let me say, I am uneasy about starting a book this way, with friends and confessions about my childhood. I am not nostalgic for that time in my life. I’m not even sure an honest account is possible. I do not trust my own memories. I tell myself so many stories about my past, as we all do. Worse—much worse—I don’t think a writer ought to insert himself into his stories this way. It generally distracts more than it deepens. A writer’s place is offstage. But what choice do I have? If I am going to tell this story, there is no way around a little autobiography. So:

When I was in sixth grade, my teacher called my parents, out of the blue, to suggest I was bored at school, which was certainly true. Had they considered sending me to a private school? Someplace rigorous and rules-y, where I would not continue to be (I will paraphrase here) a daydreamer and a smart-ass. My folks had never thought of it. They had both gone to public schools, and they presumed that fancy private schools were for Yankees. But Mom and Dad grasped the teacher’s essential meaning: what I needed was a swift kick in the pants.

So the next fall I found myself at a school that probably had not looked much different twenty or even fifty years earlier. There were no girls. There was a school necktie. Spanish was not taught, but ancient Latin was required. The gym was called a “palestra”; the cafeteria, the “refectory.” Portraits of mustachioed old “masters” hung in the hallways. There was a half-length painting of King Charles I gazing down at us with his needle nose and Vandyke beard, which alone might have cured me of daydreaming and smart-assery. Even my parents were dazzled and intimidated by the place. My mother warned me, “They smile at you, these WASPs, but I promise you, behind closed doors they call us kikes.”

Jeff Larkin felt no such anxiety when he arrived at school. He was a prince. His older brother, Alex, was a senior and a three-sport star, with the heroic aura that surrounds high school athletes. Jeff’s dad was well known too. He was a criminal defense lawyer, the kind that showed up in the newspaper or on TV standing beside a gangster, swaggering on about the incompetence of the police and the innocence of his wrongly accused client. There was a dark glamour to Mr. Larkin’s work, at least before the catastrophe, when his association with violent crime stopped being a thing to admire. But that came later.

Forbidding as the school was, at least I had a new friend. Jeff and I hit it off right away. We were inseparable. It was one of those childhood friendships that was so natural and uncomplicated, we seemed to discover it more than we created it. I have no adult friendships like the one I had with Jeff. I am sure I never will. Once we slip on the armor of adulthood, we lose the ability to form that kind of naive, unqualified connection.

But forty years later, when I got Jeff’s email in 2015, we had been out of touch for a very long time. He reached me by sending a fan email from my author website, just as any stranger would do.

“Hey,” his email read in its entirety. “Loved the book. Mr. K_____ would be proud.” (Mr. K_____ was a beloved English teacher.) “You up for a beer sometime?”

“I’m up for three,” I emailed back. “Or forty-three. Just name the place.”

The place he named was Doyle’s, an ancient pub in Jamaica Plain, now gone. It was a nostalgic choice. In our twenties, Jeff and I hung out there night after night, shooting the shit. The place had changed over the years. It was bigger and brighter now, more of a family restaurant than the grungy, patinaed old pub I remembered. But the long bar was still the same, and the ornate Victorian mirror behind the bartender.

When I arrived, Jeff was waiting at the bar. His hair was gray, and his face was fuller and more deeply lined than I had expected, but when he saw me and stood up, grinning, he became my old friend again.

“It’s the famous author, Philip Solomon,” he teased. “What an honor.” And we hugged in the clumsy, equivocal way men do.

For the next couple of hours, we drank and bantered as we always had. We picked up our conversation after twenty-odd years as if we had just seen each other the day before. I am a shy man, and I was particularly quiet during that hard time, but this night I yammered like a fool and I laughed harder than I had in a long time.

It was late, around midnight, when Jeff finally mentioned his mother’s case and the forty years of misery that followed. We had moved from the bar to a booth by then. His voice was low and confidential.

“You heard about my dad?”

“No.”

“He has Alzheimer’s.”

“Whoa. I’m sorry.”

“Convenient, isn’t it?”

“That’s not how most people think of it.”

“He gets to forget. Or pretend to.”

“You think he’s pretending?”

“I don’t know. Haven’t seen him. I get my information from Miranda.”

Miranda is Jeff’s little sister, younger by a year and a half.

“Miranda talks to him?”

“She’s taking care of him.”

I made a face:

Really? “She wants me to go see him. Before it’s too late.”

“So go. What’s the difference?”

“I wouldn’t give him the satisfaction.”

“He has Alzheimer’s. He won’t remember anyway.”

“That’s what Mimi says. She says it’s gone on long enough.” He put on a mocking tone: “I’m

lost in the maze of hate.”

“The maze of hate? That’s a thing?”

“Don’t even—I can’t.” He shook his head. “Miranda.”

“It’s a good name for a band, Maze of Hate.”

“She says when I hate him, I’m only hurting myself.”

“That could actually be true.”

“Maybe. Doesn’t mean I’m gonna stop.”

“Attaboy. You stay in that maze of hate. Great decision.”

“You should call her, Phil. She’d love to hear from you.”

“Miranda? Nah. Well, maybe. I dunno.”

“Don’t worry, I won’t tell your wife.”

“That’s very considerate, thank you.”

He gave me a dopey drunk grin. “Maybe it’ll give you something to write about.”