Excerpt

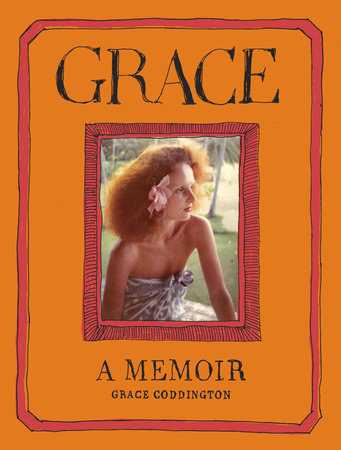

Grace

i

On Growing Up

In which the winds howl, the waves crash, the rain pours down, and our lonely heroine dreams of being Audrey Hepburn.

There were sand dunes in the distance and rugged monochrome cliffs strung out along the coast. And druid circles. And hardly any trees. And bleakness. Although it was bleak, I saw beauty in its bleakness. There was a nice beach, and I had a little sailboat called Argo that I used to drift about in for hours in grand seclusion when it was not tethered to a small rock in a horseshoe-shaped cove called Trearddur Bay. I was fifteen then, my head filled with romantic fantasies, some fueled by the mystic spirit of Anglesey, the thinly populated island off the fogbound northern coast of Wales where I was born and raised; some by the dilapidated cinema I visited each Saturday afternoon in the underwhelming coastal town of Holyhead, a threepenny bus ride away, where the boats took off across the Irish Sea for Dublin and the Irish passengers seemed never short of a drink. Or two. Or three or four.

For my first eighteen years, the Trearddur Bay Hotel, run by my family, was my only home, a plain building with whitewashed walls and a sturdy gray slate roof, long and low, with the unassuming air of an elongated bungalow. This thirty-two-room getaway spot of quiet charm was appreciated mostly by holidaymakers who liked to sail, go fishing, or take long, bracing cliff-top walks rather than roast themselves on a sunny beach. It was not overendowed with entertainment facilities, either. No television. No room service. And in most cases, not even the luxury of an en suite bathroom with toilet, although generously sized white china chamber pots were provided beneath each guest bed, and some rooms—the deluxe versions—contained a washbasin. A lineup of three to four standard bathrooms on the first floor provided everyone else’s washing facilities. For the entire hotel there was a single chambermaid, Mrs. Griffiths, a sweet little old lady in a black dress and white apron equipped with a duster and a carpet sweeper. I remember my mother being quite taken aback by a guest who took a bath and rang the bell for the maid to set about cleaning the tub. Why wouldn’t the visitors scrub it out themselves after use? she wondered.

Our little hotel had three lounges, each decorated throughout in an incongruous mix of the homely and the grand, the most imposing items originating from my father’s ancestral home in the Midlands. At an early age, I discovered that the Coddingtons of Bennetston Hall, the family seat in Derbyshire, had an impressive history that included at least two wealthy Members of Parliament, my grandfather and great-grandfather, and stretched back sufficiently into the past to come complete with an ancient family crest—a dragon with flames shooting out of its mouth—and a family motto, “Nils Desperandum” (Never Despair). And so, although some communal rooms remained modest and simple, the dining room was furnished with huge, inherited antique wooden sideboards decorated with carved pheasants, ducks, and grapes, and the Blue Room contained a satinwood writing desk hand-painted with cherubs. A large library holding hundreds of beautiful leather-bound books housed many display drawers of seashells, and various species of butterfly and beetle. There was a grand piano in the music room (from my mother’s side of the family), and paintings in gilded frames—dark family portraits—hanging everywhere else.

Guests would rise with the sun and retire to bed at nightfall. If they needed to use the telephone, there was a public booth in the bar. There was a single lunchtime sitting at one o’clock and another at seven p.m. for dinner, with only two waiters to serve on each occasion. Tea was upon request. Breakfast was served between nine and nine-thirty in the dining room—and certainly never in the bedroom. There was also a games room with a Ping-Pong table where I practiced and practiced. I was good. Very good. I would beat all the guests, which didn’t go down too well with my parents.

The sand on the long, damp beige ribbon of beach in front of the hotel was reasonably fine-grained but did get a bit pebbly as you approached the icy Irish Sea slapping against the shore. You could, however, paddle out for a fair distance before it became freezingly knee-deep.

Throughout my childhood I longed for the lushness of trees. Barely one broke the rocky surface on our side of the island. Only when we paid the occasional family visit to my father’s aunt Alice in her big, shaded house on the south side would we ever see them in numbers. My great-aunt was extremely frail and old, so I always think of her as being about a hundred. Her house was close to the small town of Beaumaris, which had a huge social life in the 1930s. My parents met there, as my mother lived nearby with her family in a sprawling house called Trecastle.

Flanking our hotel on one side was a gray seascape of cliffs, rocks, and bulrushes, then acres of windswept country and a lobster fisherman’s dwelling, and on the other Trearddur House, a prestigious prep school for boys. Once I reached the age when boys became of interest, I used to linger shyly, watching them play football or cricket beyond the gray flinty stone wall bordering their playing fields until I arrived at the bus stop and took off on my winding journey to school.

We were open from May to October but the hotel was guaranteed to be one hundred percent full only during the relatively sunny month of August, the time of the school summer holidays. Many vacationing families from the not too distant towns of Liverpool and Manchester made the effort to come and stay with us because, although it might have been easier for them to reach the more accessibly popular holiday spots of North Wales, our charming beach and village were that much more individual. At other times we were mostly empty or visited by parents who had come to join their sons for special events at the school.

Each year tumultuous clouds and fierce equinox gales announced the end of summer. A mad scramble then ensued to rescue all the little wooden sailing boats about in the bay belonging to the locals that bobbed. Llewellyn, the lobster fisherman, was in charge of having them hauled out of the sea and beached beneath the protective seawall. All winter long, while we were closed, thick mists enveloped us and rough seas pounded our shoreline. The entire place became desolate. On foggy nights you could hear the sad moan of a foghorn coming from the nearby lighthouse. It hardly ever snowed, but it rained most of the time: a constant drizzle that made the atmosphere incredibly damp, the kind of dampness that gets into your bones. So damp that, as a child, I swear I used to ache all over from rheumatism.

In the afternoons, I took long walks along the cliffs with Chuffy, my mother’s Yorkshire terrier, and Mackie, my sister’s Scottie. Stormy waves foamed and crashed over the gray rocks along the seafront, and if you missed your timing, you were liable to come in for a complete drenching whenever you dashed between them.

Throughout the endless weeks of winter, the hotel was so deserted it wasn’t worth the bother of switching on the lights. My sister and I would play ghosts. Wrapped in white sheets, we hid along the dark, empty corridors, each containing many mysterious, shadowy doorways from which you could jump out and say, “Boo!” We would wait and wait, the silence broken only by the tick-tock, tick-tock, of our big grandfather clock. But in the end, I couldn’t stand the gloom, the suspense of waiting, the sinister ticking. It was too scary, so I usually fled to the warmth and comfort of the fireside.

I was born on the twentieth of April 1941 in the early part of World War II, the same year the Nazis engulfed Yugoslavia and Greece. I was christened Pamela Rosalind Grace Coddington. My elder sister Rosemary, or Rosie for short, was the one who choose Pamela as my registered first name, which then became abbreviated to Pam by most people we knew.

Marion, my maternal grandmother, was a Canadian opera singer who had fallen in love with my grandfather while visiting Wales on a singing tour. He followed her back to Canada, where they married and where my mother and her brother and sister were born. For a while they lived on Vancouver Island, which was heavily wooded and filled with bears. Then they moved back permanently to Anglesey, where my grandmother grew more and more morose and wrote terribly sad poetry. I’m told my grandfather was somewhat extreme when it came to what he perceived as correct behavior. Apparently, he once locked my grandmother in the downstairs bathroom—which he had designated for gentlemen only—for an entire day when she had used it in an emergency.

Janie, my mother, inherited this strict, no-nonsense Victorian attitude and believed that children should be seen and not heard. She demanded absolute obedience but never lost her temper or raised her voice. It was a given that I would make my bed and tidy my room, and that I had my chores to fulfill. She was the strong, stoic one who held our family together. Photographs of her from the 1920s show a sleek and prosperous-looking woman. She drew and painted rather well in watercolors and played the piano and the Spanish guitar. Welsh—although she preferred to think of herself as English—she could trace the family lineage back to the Black Prince. (In fact, we weren’t encouraged to think of ourselves as Welsh at all; more as foreigners, émigrés from Derbyshire.)