Excerpt

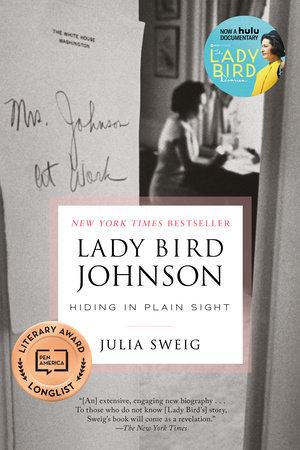

Lady Bird Johnson: Hiding in Plain Sight

Chapter 1The SurrogateNeither the fanatics nor the faint-hearted are needed. And our duty as a party is not to our party alone, but to the nation, and indeed to all mankind. Our duty is not merely the preservation of political power but the preservation of peace and freedom.

So let us not be petty when our cause is so great, let us not quarrel amongst ourselves when our nation’s future is at stake. —John F. Kennedy, speech to have been delivered in Austin, Texas, November 24, 1963

When he came to the White House, suddenly everyone saw what the New Frontier was going to mean.

It meant a poet at the Inauguration; it meant swooping around Washington, dropping in on delighted and flustered old friends; it meant going to the airport in zero weather without an overcoat; it meant a rocking chair and having the Hickory Hill seminar at the White House when Bobby and Ethel were out of town; it meant fun at presidential press conferences.

It meant dash, glamour, glitter, charm. It meant a new era of enlightenment and verve; it meant Nobel Prize winners dancing in the lobby; it meant authors and actors and poets and Shakespeare in the East Room. —Mary McGrory, The Evening Star, November 24, 1963

Claudia Taylor Johnson drew her initial impression of Jacqueline Bouvier Kennedy not from a luncheon for spouses or an evening social event in Washington, but rather, from Jack and Jackie’s 1953

Life magazine wedding pictures. Jackie, she thought, was “absolutely the essence of romance and beauty.” When the newlywed Kennedys moved to Washington, real life, as it turned out, was even more remarkable than the photos. As a freshman senator’s wife, Jackie was “a bird of beautiful plumage” who “couldn’t have been more gracious.” By comparison, Bird felt, she and the other Senate wives were “little gray wrens.” When the Kennedys married and Jack began his first term in the Senate, the Johnsons had already been in that chamber for four years. In the Washington, D.C., of the 1950s, the Johnsons and the Kennedys were not personally close. They didn’t run in the same social circles. In fact, by the 1956 Democratic convention, Jack and Lyndon had become quasi-overt rivals. Elected Senate majority leader in 1955 and approaching the peak of his power in Congress, LBJ conveyed his standing to Lady Bird, who ruled the roost of Senate wives. Despite the differences between their husbands, Bird graciously inducted Jackie into the carefully choreographed courtlike world of Washington spouses, hosting her at their brick Colonial on 30th Place, Northwest, and otherwise brushing up against her youth and glamour throughout the decade. Finding Jackie impossibly young, Lady Bird worked to put her at ease at these spouse gatherings; Jackie liked Lady Bird and made a point of connecting with the Johnsons’ elder daughter, Lynda, just eleven when they first met. But Washington was not entirely new to Jackie: At fourteen, she’d moved with her mother and her mother’s new husband to an estate in Virginia’s hunt country. She briefly attended the private girls’ school Holton-Arms, and she finished her undergraduate degree at George Washington University before marrying Jack.

An accomplished equestrian, Jackie summered in the Hamptons and Newport; had studied at Miss Porter’s School, Vassar, and the Sorbonne; and spoke French and Spanish. Lady Bird had studied French, briefly, and her Spanish was still limited to what she had picked up during her childhood in Texas. Jackie was twenty-three years old, Bird’s age when Lyndon had already served for two years in the House. While Bird worked assiduously to grease the wheels of Lyndon’s political office with endless socializing, charity events, and travel back and forth to and across Texas, Jackie struck Bird as being uninterested in the tedium of the game, content to spend her early years married to Jack as a society photographer for the Washington Times-Herald, taking a course in American history at Georgetown, or repairing to Hickory Hill, the country house in McLean, Virginia, that the newlyweds had purchased and later gave to Bobby and Ethel. Even if outward the cultural signs of their differences were rife, inward, the parallels between Lady Bird and Jackie ran deep. Each had made her mark in Washington as the young, newlywed wife of a young, ambitious husband. Both soon had to contend with their husbands’ infidelities and the humiliation of knowing that their own political and social circles knew of and, indeed, often facilitated the behavior. Miscarriage after miscarriage plagued their quest for offspring. And by 1960, both had husbands for whom serious illness made the prospect of death loom large—Addison’s disease dogged JFK throughout his adult life; depression, heart disease, and other itinerant maladies afflicted Lyndon. Both their husbands smoked and drank too much. Yet, it was not until the 1960 campaign that Jackie and Lady Bird had real occasion to fully evaluate each other. By pairing their husbands on a surprise presidential ticket, the party convention that summer in Los Angeles forced upon the two women a rapid, at times uncomfortable bond, but one that eventually grew into a lifelong empathy and unexpected intimacy.

* * *

Neither Lyndon nor Lady Bird went to the 1960 Los Angeles convention with the ambition of landing the vice-presidential slot. Having turned down Joe Kennedy’s earlier offer to finance an LBJ-JFK ticket in 1956, Lyndon had instead delivered the Texas delegation for JFK’s own failed bid for the vice presidency during the Democratic National Convention in Chicago that year—former Illinois governor Adlai Stevenson was the presidential nominee—on the surface a magnanimous gesture, but one unambiguously intended to telegraph to the young senator and his family that LBJ had the power to act as kingmaker within the party. But by the end of the decade, Joe, Jack, and Bobby made their play to build a national profile and organization to elect Jack to the White House. By 1960, much to the Kennedy clan’s distaste, they needed LBJ, for his regional roots and political chops. In assessing his own prospects for a presidential run, Johnson remained clear-eyed that while as majority leader he could organize massive support in the U.S. Senate, his leverage in Congress would not automatically translate into the national stature necessary for a successful presidential run. After working as a congressional staffer and then running a New Deal youth employment program in Austin, he won his first House seat in a special election in 1937 with ten thousand dollars in financing from Lady Bird’s inheritance. He went on to win it handily, and mostly unopposed, in 1938, 1940, 1942, 1944, and 1946. He lost a bid for the Senate in 1941, and in 1948 he authorized a fraudulent voting operation to secure victory against a primary opponent, winning by just 87 votes, before winning in the general election that year.

Ambivalence, the prospect of loss, the suggestion of illegitimacy—these were constant themes in Lyndon Johnson’s political career. From Lady Bird’s perspective when it came to national office, her husband had been “deeply uncertain about his ability, his health, his being a southerner, whether that was a good thing for him to do.” Yet, by the end of 1959, Lyndon, she recalled, had about “sucked the orange dry” from his tenure as Senate majority leader. “We were reaching a point of no return, a certain defining of pathways” leading toward a presidential bid for Lyndon. Despite his mentor Congressman Sam Rayburn and his longtime aide, future Texas governor John Connally, pushing LBJ to publicize his campaign for the top of the ticket more aggressively, Lady Bird’s husband had instead run an undeclared, ambivalent campaign in 1960. Bird had been at her dying father’s bedside in a hospital in Marshall, Texas, a trip she would make five times that year, when what she knew to be a halfhearted Lyndon finally announced his candidacy just three days before the kickoff of the 1960 convention in Los Angeles. By then, Bobby Kennedy’s national strategy for his brother’s campaign enabled JFK to trounce LBJ by more than double in the first delegate ballot. The night after the bruising defeat, Lady Bird and Lyndon treated themselves to “the best night’s sleep we’d both had in a long time.” But the defeat was a humiliation, and only the first.