Excerpt

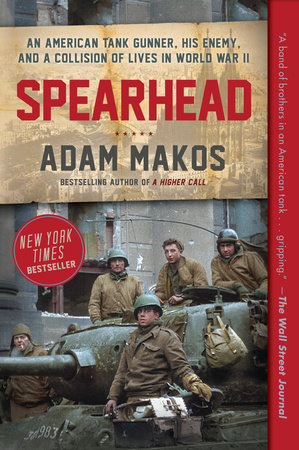

Spearhead

Chapter 1

The Gentle Giant

September 2, 1944

Occupied Belgium, during World War II

Twilight fell on a country crossroads.

The only sounds came from insects buzzing in the surrounding blue fields, and something else. Metallic. The sound of hot engines ticking and pinging, decompressing after a long drive.

With silent efficiency, tank crewmen worked to rearm and refuel their tired Sherman tanks before the last hues of color fled the sky.

Crouched behind the turret of the leftmost tank, Corporal Clarence Smoyer carefully shuttled 75mm shells into the waiting hands of the loader inside. It was a delicate job—even the slightest clang could reveal their position to the enemy.

Clarence was twenty-one, tall and lean with a Roman nose and a sea of curly blond hair under a knit cap. His blue eyes were gentle, but guarded. Despite his height, he was not a fighter—he had never been in a fistfight. Back home in Pennsylvania he had hunted only once—for rabbit—and even that he did halfheartedly. Three weeks earlier he’d been promoted to gunner, second in command on the tank. It wasn’t a promotion he had wanted.

The platoon was in place. To Clarence’s right, four more olive-drab tanks were fanned out, “coiled,” in a half-moon formation with twenty yards between each vehicle. Farther to the north, beyond sight, was Mons, a city made lavish by the Industrial Revolution. A dirt road lay parallel to the tanks on the left, and it ran up through the darkening fields to a forested ridge, where the sun was setting behind the trees.

The Germans were out there, but how many there were and when they’d arrive, no one knew. It had been nearly three months since D-Day, and now Clarence and the men of the 3rd Armored Division were behind enemy lines.

All guns faced west.

Boasting 390 tanks at full strength, the division had dispersed every operational tank between the enemy and Mons, blocking every road junction they could reach.

Survival that night would hinge on teamwork. Clarence’s company headquarters had given his platoon, 2nd Platoon, a simple but important mission: guard the road, let nothing pass.

Clarence lowered himself through the commander’s hatch and into the turret, a tight fit for a six-foot man. He slipped to the right of the gun breech and into the gunner’s seat, leaning into his periscopic gun sight. As he had no hatch of his own, this five-inch-wide relay of glass prisms and a 3x telescopic gun sight mounted to the left of it would be his windows to the world.

His field of fire was set.

There would be no stepping out that night; it was too risky even to urinate. That’s what they saved empty shell casings for.

Beneath Clarence’s feet, the tank opened up in the hull, with its white enamel walls like the turret’s and a trio of dome lights. In the bow, the driver and bow gunner/assistant driver slid their seats backward to sleep where they had ridden all day. On the opposite side of the gun breech from Clarence, the loader stretched a sleeping bag on the turret floor. The tank smelled of oil, gunpowder, and a locker room, but the scent was familiar, even comforting. Ever since they’d come ashore, three weeks after D-Day, this M4A1 Sherman had been their home in Easy Company, 32nd Armor Regiment, of the 3rd Armored Division, one of the army’s two heavy tank divisions.

Tonight, sleep would come quickly. The men were exhausted. The 3rd Armored had been charging for eighteen days at the head of the First Army, leading two other divisions in the breakout across northern France. Paris had been liberated, the Germans were running back the way they’d come in 1940, and the 3rd Armored was earning its nom de guerre: the Spearhead Division.

Then came new orders.

The reconnaissance boys had spotted the German Fifteenth and Seventh Armies moving to the north, hightailing it out of France for Belgium and on course to pass through Mons’s many crossroads. So the 3rd Armored turned on a dime and raced north—107 miles in two days—arriving just in time to lay an ambush.

The tank commander dropped into the turret and lowered the split hatch covers, leaving just a crack for air. He slumped into his seat behind Clarence, his boyish face still creased by the impression of his goggles. Staff Sergeant Paul Faircloth of Jacksonville, Florida, was also twenty-one, quiet and easygoing, with a sturdy build, black hair, and olive skin. Some assumed he was French or Italian, but he was half Cherokee. As the platoon sergeant, Paul had been checking on the other crews and positioning them for the night. Normally the platoon leader would do this, but their lieutenant was a new replacement and still learning the ropes.

For two days Paul had been on his feet in the commander’s position, standing halfway out of his hatch with the turret up to his ribs. From there he could anticipate the column’s movements to help the driver brake and steer. In the event of a sudden halt—when another crew threw a track or got mired in mud, for instance—Paul was always the first out of the tank to help.

“I’m taking your watch tonight,” Clarence said. “I’ll do a double.”

The offer was generous, but Paul resisted—he could handle it.

Clarence persisted until Paul threw up his hands and finally swapped places with him to nab some shut-eye in the gunner’s seat.

Clarence took the commander’s position, a seat higher in the turret. The hatch covers were closed enough to block a German grenade, but open enough to provide a good view to the front and back. He could see his neighboring Sherman through the rising moonlight. The tank’s squat, bulbous turret looked incongruous against the tall, sharp lines of the body, as if the parts had been pieced together from salvage.

Clarence snatched a Thompson submachine gun from the wall and retracted the bolt. For the next four hours, enemy foot soldiers were his concern. Everyone knew that German tankers didn’t like to fight at night.

Partway through Clarence’s watch, the darkness came alive with a mechanical rumbling.

The moon was smothered by clouds and he couldn’t see a thing, but he could hear a convoy of vehicles moving beyond the tree-lined ridge.

Start and stop. Start and stop.

The radio speaker on the turret wall kept humming with static. No flares illuminated the sky. The 3rd Armored would later estimate there were 30,000 enemy troops out there, mostly men of the German Army, the Wehrmacht, with some air force and navy personnel among them—yet no order came to give pursuit or attack.

That’s because the battered remnants of the enemy armies were bleeding precious fuel as they searched for a way around the roadblocks, and Spearhead was content to let them wander. The enemy was desperately trying to reach the safety of the West Wall, also known as the Siegfried Line, a stretch of more than 18,000 defensive fortifications that bristled along the German border.

If these 30,000 troops could dig in there, they could bar the way to Germany and prolong the war. They had to be stopped, here, at Mons, and Spearhead had a plan for that—but it could wait until daylight.

Around two a.m. the distinctive slap of tank tracks arose from the distant rumble.

Clarence tracked the sounds—vehicles were coming down the road in front of him. He knew his orders—let nothing pass—but doubt was setting in. Maybe this was a reconnaissance patrol returning? Had someone gotten lost? They couldn’t be British, not in this area. Whoever they were, he wasn’t about to pull the trigger on friendly forces.

One after the other, three tanks clanked past the blacked-out Shermans and kept going, and Clarence began to breathe again.

Then one of the tanks let off the gas. It began turning and squeaking, as if its tracks were in need of oil. The sound was unmistakable. Only full-metal tracks sounded like that, and a Sherman’s were padded with rubber.

The tanks were German.

Clarence didn’t move. The tank was behind him, then beside him. It slowed and sputtered then squeaked to a stop in the middle of the coiled Shermans. Clarence braced for a flash and the flames that would swallow him. The German tank was idling alongside him. He’d never even hear the gun bark. He would just cease to exist.

A whisper shook Clarence from his paralysis. It was Paul. Without a word, Clarence slipped back into the gunner’s seat and Paul took over.

Clarence strapped on his tanker’s helmet. Made of fiber resin, it looked like a cross between a football helmet and a crash helmet, and had goggles on the front and headphones sewn into leather earflaps. He clipped a throat microphone around his neck and plugged into the intercom.

On the other side of the turret, the loader sat up, wiping the sleep from his eyes.

Clarence mouthed the words German tank. The loader snapped wide-awake.

From his hatch, Paul tapped Clarence on the right shoulder, the signal to turn the turret to the right.

Clarence hesitated. The turret wasn’t silent, what if the Germans heard it?

Paul tapped again.

Clarence relented and turned a handle, the turret whined, gears cranked, and the gun swept the dark.

When the gun was aligned broadside, Paul stopped Clarence. Clarence pressed his eyes to his periscope. Everything below the skyline was inky black.

Clarence told Paul he couldn’t see a thing and suggested they call in armored infantrymen to kill the tank with a bazooka.

Paul couldn’t chance some jittery soldier blasting the wrong tank. He grabbed his hand microphone—nicknamed “the pork chop” due to its shape—and dialed the radio to the platoon frequency, alerting the other crews to what they likely already knew: that an enemy tank was in the coil. In a Sherman platoon at that time, only the tanks of the platoon leader and platoon sergeant could transmit. Everyone else could only listen.

“No noise, and no smoking cigarettes,” Paul said. “We’ll take care of him.”

We’ll take care of him? Clarence was horrified. He had hardly used the gun in daylight and now Paul wanted him to fire in pitch-darkness, at what? A sound? An enemy he couldn’t see?

He wished he could return to being a loader. A loader never saw much. Never did much. On a tank crew, the loader was pretty much just along for the ride. That was the good life. A gentle giant, Clarence simply wanted to slip through the war without killing anyone or getting killed himself.

No time for that. The German tank crew had likely realized their mistake by now.

“Gunner, ready?”

Panicked, Clarence turned and tugged on Paul’s pant leg.

Paul sank into the turret, exasperated. Clarence rattled off his doubts. What if he missed? What if he got a deflection and hit their own guys?

Paul’s voice calmed Clarence: “Somebody has to take the shot.”

As if the Germans had been listening, they suddenly cut their power. The hot engine hissed, then went silent.

Clarence felt a wave of relief. It was a reprieve. Paul must have been biting his lip in anger, because he said nothing at first. Finally, he informed the crew that now they would have to wait to fire at first light.

Clarence’s relief faded. His indecision had cost them whatever advantage they’d had. And against a German tank, they’d need every advantage they could get, especially if they were facing a Panther, the tank of nightmares. Some GIs called it “the Pride of the Wehrmacht,” and rumor had it that a Panther could shoot through one Sherman and into a second, and its frontal armor was supposedly impervious.

That July, the U.S. Army had placed several captured Panthers in a field in Normandy and blasted away at them with the same 75mm gun as in Clarence’s Sherman. The enemy tanks proved vulnerable from the flanks and rear, but not the front. Not a single shot managed to penetrate the Panther’s frontal armor, from any distance.

Clarence checked his luminescent watch, knowing the Germans were probably doing the same. The countdown had begun. Someone was going to die.

The loader fell asleep over the gun breech.

Three a.m. became four a.m.

Clarence and Paul passed a canteen of cold coffee back and forth. They had always joked that they were a family locked in a sardine can. And like a family, they didn’t always see eye to eye. Unlike Paul, who was always running off to help someone outside the tank, all Clarence cared about was his family on the inside—him and his crew.

This had been his way since childhood.

Growing up in industrial Lehighton, Pennsylvania, Clarence lived in a row house by the river, with walls so flimsy he could hear the neighbors. His parents were usually out working to keep the family afloat. His father did manual labor for the Civilian Conservation Corps and his mother was a housekeeper.

With the family’s survival at stake, Clarence was determined to contribute. When other kids played sports or did homework, twelve-year-old Clarence stacked a ballpark vendor’s box with candy bars and went selling door-to-door throughout Lehighton. Just a boy, he had vowed: I’ve got to take care of my family because no one is going to take care of us.

Clarence checked his periscope. To the east, a faint tinge of purple colored the horizon.

He kept his eyes glued to the glass until a blocky shape appeared about fifty yards away.

“I see it,” he whispered.

Paul rose to his hatch and saw it too. It looked like a rise of rock, highest at the midpoint. Clarence turned handwheels to fine-tune his aim.

Paul urged him to hurry. If they could see the enemy, the enemy could see them.

Clarence settled the reticle, as the gun sight’s crosshairs were known, on the “rock” at center mass and reported that he was ready. His boot hovered over the trigger, a button on the footrest.

“Fire,” Paul said.

Clarence’s foot stamped down.

Outside, a massive flash leapt from the Sherman’s barrel, momentarily illuminating the tanks—an olive-drab American and a sandy-yellow German—both facing the same direction.

Sparks burst from the darkness and a sound like an anvil strike pierced the countryside. Inside the turret, without the fan operating, smoke hung thick in the air. Clarence’s ears throbbed and his eyes stung, but he kept them pressed to his sight.

The loader chambered a new shell. Clarence again hovered his foot over the trigger.

“Nothing’s moving,” Paul said from above. A broadside at this range? It was undoubtedly a kill shot.

The intercom came alive with voices of relief, and Clarence moved his foot away from the trigger.

Paul radioed the platoon; the job was done.

Through his periscope, Clarence watched the sky warm beneath the dark clouds, revealing the boxy armor and the 11-foot, 8-inch long gun of a Panzer IV tank.

Known by the Americans as the Mark IV, the design was old, in service since 1938, and it had been the enemy’s most prevalent tank until that August, when the Panther began taking over. But even though it was no longer the mainstay, the Mark IV was still lethal. Its 75mm gun packed 25 percent more punch than Clarence’s.

More light revealed the tank’s dark green-and-brown swirls of camouflage and the German cross on the flank. Clarence had nearly placed his shot right on it.

“Think they’re in there?” One of the crewmen posed the question, seeing that the Mark IV’s hatch covers hadn’t budged.

Clarence envisioned a tank full of moaning, bleeding men and hoped the crew had slipped out in the night. He had no love for the Germans, but he hated the idea of killing any human being. He wasn’t about to look inside his first tank kill. A shell can ricochet like a super-sonic pinball within the tight quarters, and he’d seen maintenance guys go inside to clean and come out crying after discovering brains on the ceiling.

“I’ll go.” Paul unplugged his helmet.

Clarence tried to dissuade him. It wasn’t worth looking inside and getting his head blown off by a German.

Paul brushed away the concerns and radioed the platoon to hold their fire.

Through his periscope, Clarence watched Paul climb the Mark IV’s hull and creep toward the turret with his Thompson at the ready. With one hand steadying his gun, Paul opened the commander’s hatch and aimed the Thompson inside.

Nothing happened.

He leaned forward and took a long look, then shouldered his gun. Paul sealed the hatch shut.