Excerpt

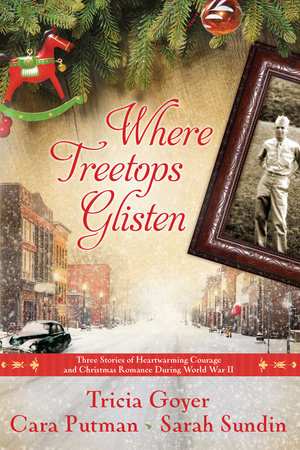

Where Treetops Glisten

White Christmas by Cara PutmanExcerpted from

Where Treetops Glisten by Tricia Goyer, Cara Putman, and Sarah Sundin

Thursday, October 29, 1942Lafayette, Indiana Tackle your greatest fear? Professor Plante had smiled as he issued his challenge, as if the assignment was easy to achieve. Even a privilege. Yet five minutes after class ended, Abigail Turner remained frozen at her desk. A school project worth twenty-five percent of her grade tied to her greatest fear? And one that had to be developed and completed before the holidays? The professor called it a simple way to overcome the past by focusing on the future. A way to explore the principles they’d discussed and apply them to their own lives before trying the ideas on future clients. Didn’t he see how tied the two were? How there was nothing simple about confronting dark moments in the past that were best avoided?

Abigail pushed back from the desk and joined the last students streaming through the door to the hall. She didn’t notice anyone else who had broken into a cold sweat at the professor’s instructions. In fact, most joked and bantered like another week of school was almost over, leading to another weekend of studying, Purdue football, and any odd jobs they worked. Maybe her fellow students didn’t carry the fears and weight of the past as tightly as she did.

She tried to shake it off as she’d done over the years. She still had weeks to create the right experience for the project—at least until the end of the semester. Professor Plante had even made it sound like the students could have longer if they didn’t mind an incomplete on their transcript.

As Abigail entered the hallway of Purdue’s University Hall, she froze. The October wind gusted through the door and toyed with her hat, but that didn’t account for her inability to move. No, she could only blame that on the reality that if she was truly to do this assignment, she had to find a way to open her heart to someone else. How could she make Professor Plante or anyone else understand that she couldn’t do that? Not when it risked someone else leaving her.

“I have to get to work.” She whispered the words as she tightened her grip on her bag, which was loaded down with textbooks, then forced her legs to move.

What would her life be like if Sam Troy, her high school love, hadn’t enlisted and then died that terrible day the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor? With his death, her carefully constructed dreams for the future crashed into an abyss, one she couldn’t seem to climb from.

She glanced at her watch and frowned. If she dawdled any more, she’d miss the bus that would carry her down the hill, across the Wabash River, and to downtown Lafayette in time for her shift at Glatz Candies. With the weekend approaching, she looked forward to a couple of days to concentrate on the confections that made the restaurant and candy shop known around town. Soon she’d learn the secret to making the popular candy canes. Maybe she could coax the owner into teaching her the tricks to the twisted sweet that night.

“Slow down, Abigail.”

Abigail grinned as her classmate Laurie Bertsche hurried up, her polo coat buttoned to her throat.

Abigail nudged her friend in the shoulder. “It’s not cold enough for that coat yet.”

“I’m from Florida. We don’t do cold.”

“Then why pick Purdue?”

“It picked me, since it was as far away from home as I could afford.” Laurie shuddered and gripped the coat around her throat. “What do you think of that assignment?” She rushed on before Abigail could interrupt. “It should be fun to think of something. There are so many people who need help.” Laurie paused, frowned for a moment, then shrugged. “I’m not sure what I’ll do yet. Do you have ideas?”

“Not yet.”

“You’re so intense; I know you’ll come up with something brilliant.” Merriment danced in Laurie’s green eyes. “I need a favor tomorrow night. One of the guys I know from town asked me to a movie and dance. I said yes, but the problem is he has a buddy. Say you’ll join us.”

“You know my stance on boys.”

Laurie singsonged as they waltzed through the doors. “No dating until this war business is over.” She paused and a serious glint entered her expression. “This isn’t a boy like you’d see here. He’s not a student, but a man supporting his family.”

“I can’t, Laurie. If he’s not in the military yet, he will be any day. Life is too uncertain to risk even friendship.” Abigail had certainly learned that lesson between Sam, her brother Alfie, and her sister Annie. Professor Plante wanted her to confront her fears by acting in opposition to those very fears that life had branded into her. How could she do something and then write an essay explaining how the action had changed her? What if she did something and found she was still afraid of losing someone she loved? Should she help the military boys in some way? Or should she focus on children? Would either satisfy her professor?

“You mean you

won’t. I intend to have a great time with Joey, but I wish you’d come. Joey’s friend seems nice, and you don’t need to worry that it will be for more than one night. Now if something develops with Joey, that’s just icing for me.”

“Try ice on the Wabash,” Abigail mumbled. “The kind you fall through.” The kind that broke your heart into shattered pieces, like the fragile ice coating the wide river, and left you frozen inside when you fell into the cold current.

Laurie shook her head. “Too early for that kind of ice. I’ll have enough fun for the two of us. Call if you change your mind. If not, I’ll see you in class Monday.”

The rumble of the bus on State Street warned Abigail she’d better hurry.

Don’t leave! I can’t be late for work. She waved frantically as the driver shifted the bus into gear. She rushed into State Street, waving. Brakes screeched and someone tugged her back to the curb right before a car whizzed by, horn blaring. Her heart stuttered in her chest. She’d come too close to landing under the wheels of that car.

“You all right, miss?”

“Thanks to you.” She turned to her rescuer, and his gaze captured her, a mix of sadness and concern swirling in his eyes.

“You coming? Or standing out there all day?”

Heat flooded Abigail’s cheeks at the bus driver’s barked words. After checking for traffic, she hurried across the street, then tripped up the stairs, thrust a token into the box, and stepped down the aisle, barely noticing the young man who had rescued her following with a slight limp. The grinding gears and the bus’s accompanying lurch pushed her down the aisle, and she

collapsed onto an empty seat. The young man took the one opposite her.

She glanced at him under her lashes, noting the broad shoulders that indicated a life of work. There was something about him, as if his dog had just died, that made her want to reach out.

He slouched in his seat, hands clasped in his lap, shoulders slumped forward. A hat was crammed on top of dark hair that curled at the nape of his neck, longer than the regulation cuts worn by enlisted men. There was something familiar about him, yet she was certain they’d never been introduced. Abigail shrugged off the feeling. Even in the United States’ heightened war machine during 1942, Purdue’s campus flowed with men. The difference was many wore a uniform. This one didn’t. Why? Could it be whatever had caused his limp?

His glance rose, colliding with hers. Caught. He’d discovered her staring. Still she couldn’t look away, not when such uncertainty resided in the pools of his hazel eyes. Something inside her froze, caught between wanting to help and distancing herself from the pain she saw reflected in the depths of his gaze.

Maybe the pain was what she recognized.

She swallowed around a sudden tightness in her throat. “Thank you for what you did out there.”

“You’re welcome.” His deep voice made it sound like it was nothing. He simply took heroic actions every day.

“I’m Abigail. Abigail Turner.”

“Jackson Lucas.” He looked back down at his hands.

Abigail felt the chill of the disconnection. She yanked a psychology text from the bag at her feet and opened it to the next chapter. The short ride would be better used preparing for Monday’s class than wondering about the man seated across the aisle from her.

Her vow to avoid romantic relationships, no matter how casual, had not been some fly-by-night decision. She had carefully considered her course after Sam’s death.

***

I’ll Be Home for Christmas by Sarah SundinExcerpted from

Where Treetops Glisten by Tricia Goyer, Cara Putman, and Sarah Sundin

Friday, December 3, 1943Lafayette, Indiana Grace Kessler poked harder at the typewriter keys, trying to drown out the song. Her fingers betrayed her and tapped to the rhythm. Why did Ruby Schmidt insist on singing in the secretarial pool? Why did she have to choose Christmas songs? And couldn’t she at least pick a song with a faster beat?

Grace deciphered her shorthand notes on the spiral-bound tablet to her right and finished a business letter from Mr. Dubois in Alcoa’s procurement department to Mr. Parkhurst with the War Production Board. She zipped the letter out of the typewriter, removed the carbon paper, and laid the original in her outgoing basket and the copy in the file basket.

Alcoa was America’s top producer of aluminum, crucial for the production of airplanes and other defense materials. A secretary’s work might not be as glamorous as a nurse or a WAVE or a Rosie the Riveter, but it allowed Grace to support both her daughter and the war effort.

Grace’s gaze slid to the silver picture frame on her desk, which held the last photo taken of George and Linnie together, over two years earlier. Linnie had just turned four. She sat on George’s lap, and father and daughter grinned at each other with total adoration. No little girl could have loved her daddy more.

Pain rose in Grace’s heart, and she ripped her attention back to the typewriter. The faster she typed, the faster Alcoa could produce aluminum, the faster planes could come off the assembly line, and the sooner this war would be over and no more men would be shot down by Japanese bullets over Filipino jungles.

They never even found George’s body.

“I’ ll be home for Christmas . . .” Ruby’s song drifted closer.

Grace winced. No, he wouldn’t.

Something scratched the top of Grace’s head, and Ruby giggled.

“Ouch.” Grace extracted a little leafy branch from her hairdo—and a couple strands of her own dark brown hair.

“Mistletoe, sweetie.” Ruby puckered lips as red as holly berries. “You need some Christmas spirit.”

Grace replaced a bobby pin and forced herself to smile and wink at Ruby. “I need to get back to work, and so do you.”

Ruby fluffed her platinum hair. “You need a date in the worst possible way. Bobby knows the nicest young man—”

“No.” Grace pinned her strongest look on the girl. “No blind dates. Besides, who in this town would agree to baby-sit Linnie?”

“She’s a handful, isn’t she?”

“Yes, she is.” Grace rolled new paper into her typewriter, flipped the release lever, and aligned the sheet. “You’d best get back to work before Norton sees you.”

Sure enough, the door to the supervisor’s office swung open. Grace swept the mistletoe into her lap and handed a blank piece of paper to Ruby. “Thank you for taking care of this, Miss Schmidt.”

“You’re welcome, Mrs. Kessler.” Ruby skedaddled back to her desk.

“Mrs. Kessler.” Mrs. Norton glared at Grace. “Phone call. Your baby-sitter.”

Sympathetic murmurs rose from the other secretaries, but Grace’s lips and fingertips went numb. Not again.

Somehow she stood. She hid the mistletoe in the hip pocket of her bottle-green suit jacket and walked on wobbly ankles down the aisle between all the clattering typewriters.

“Thank you, Mrs. Norton.” She edged past her matronly supervisor and through the doorway to the office.

Mrs. Norton crossed her plump arms. “You’re the only one, Mrs. Kessler. The only one who takes so many personal calls. You need to get a handle on that child of yours.”

“Yes ma’am.” Grace turned her back on her supervisor to hide her anguish, and she picked up the receiver. “Mrs. Harrison?”

“I’ve had it. I’ve had it up to here.” The baby-sitter’s voice climbed and shivered. “When she’s here . . . oh, my nerves! And when she goes wandering, well, just how much can a woman take?”

Grace clenched the cold black receiver. “Is Linnie there?”

“Of course not. She’s trying to kill me, I’m sure of it.”

Inside Grace, frustration with Mrs. Harrison wrestled with worry for Linnie. The clock read 4:05. Linnie should have arrived half an hour earlier. Teaching her daughter how to ride the bus had been necessary when Linnie started school in September, but it only encouraged her wandering. Her searching.

Mrs. Harrison jabbered about her nerves, and guilt filled Grace. What kind of mother allowed her six-year-old daughter to roam the city alone?

“Excuse me, Mrs. Harrison. I need to call the police.” Again.

“This is it. This is the last time. I simply cannot take it any longer. I quit.”

Outside the tiny office window, Alcoa’s red brick smokestack jutted into the gray sky. Grace laid down the receiver, missed, and finally settled it in place.

Mrs. Norton sniffed. “Don’t even think about asking to get off early.”

“I know, ma’am.” Grace’s voice came out choked. “May I make another call, please?”

“I ought to charge you.”

Grace dialed 4045 for the Lafayette Police Department, a number she knew by heart. While the phone rang, she rubbed the aching knot at the base of her skull.

Lord, please keep my baby safe.So many horrible things could happen to her little girl. And her job. She’d worn out every available baby-sitter.

How could she stay employed without a baby-sitter? And without a job, how could she pay the bills?

Worst of all, Grace’s love wasn’t enough for her daughter.

That knowledge hollowed into her soul.

_________

Lieutenant Pete Turner trudged down Sixth Street, hands deep in the pockets of his olive drab trousers, his pilot’s crush cap shoved low on his forehead.

He passed Glatz Candies on the far side of the street, angling his head away from the cheery red-and-white awning. A year ago, he would have bugged his little sister Abigail behind the counter and savored an ice cream soda.

Not now. Nothing sounded good. Not ice cream, not teasing, not even family.

A two-hundred-hour combat tour flying a P-47 Thunderbolt fighter plane over Nazi-occupied

Europe had drained him of all grief, all anger, and all joy. So many deaths. So many good young men gone down in flames.

The marquee of the Lafayette Theater advertised

For Whom the Bell Tolls. Pete had read Hemingway’s book. He’d memorized John Donne’s poem at

Jefferson High.

“Never send to know for whom the bell tolls,” Pete muttered, “it tolls for thee.”

Today even Pastor Hughes hadn’t helped. All Pete wanted was a few words of wisdom and comfort to make him feel again. Feel anything.

The pastor had gotten him through his big brother Alfred’s death back in ’27, when Pete was fifteen. Pete owed Pastor Hughes for his salvation, for his very life.

But today? Pastor Hughes had leaned back in his leather chair, holding his reading glasses and rubbing them with a handkerchief while Pete talked. Didn’t he understand how hard it was for Pete to spill his guts? And the pastor just rubbed his glasses.

When Pete was done talking, Pastor Hughes leaned forward and said, “Give.”

Give?

“When you’re empty inside,” Pastor Hughes said, “the best thing you can do is give. Find a need, step outside of yourself, and give.”

Pete turned right onto Columbia Street. Maybe the pastor was going senile. Pete was an empty pitcher. How could he pour anything out from nothing?

He’d have to find his own way to fill up again. And soon. On January 1, he had to report for transition training with the Air Transport Command Ferrying Division. He had to fly again.

Maybe that was why he was roaming downtown. To fill up on all the sights he’d grown up with. The memories of a lifetime called out from each brick.

He squinted at the buildings, at the trees in their square holes in the sidewalk, at the overcast sky. He trained his senses to the chill in the air, the sounds of traffic—light as it was—and the conversations of passersby. But he didn’t feel anything.

Ahead of him rose the high pointy dome of the Tippecanoe County Courthouse in all its Victorian glory. Pete and his best friend, Scooter, had loved running around the grounds, playing cops and robbers. How many times had they decorated the statue of the Marquis de Lafayette or added soap to the fountain at his feet? How many times had they been caught?

The thought should have summoned up either guilt or a smile. Nope. Nothing.

He headed down the left side of the street, across from the courthouse. A few blocks more and he’d reach the Wabash River. Maybe the sound of running water would awaken something.

The door of Loeb’s department store opened, and Pete held the door for two ladies burdened with packages. When they thanked him, he said, “You’re welcome” but couldn’t smile. How could he with that infernal song billowing through the open door?

***

Have Yourself a Merry Little Christmas by Tricia GoyerExcerpted from

Where Treetops Glisten by Tricia Goyer, Cara Putman, and Sarah Sundin

Thursday, December 21, 1944Nieuwenhagen, the Netherlands Gray. The color of the sky outside the makeshift hospital. Gray. The bare tree limbs that reached into the horizon, as if offering naked prayers for the Dutch countryside and its war-torn people.

Gray. The ashen faces of the soldiers as the stretcher bearers carried them in on litters. American soldiers, mostly, but Germans too, like the man who lay on the cot before her.

Meredith Turner tried to be gentle as she bandaged the shoulder of the unconscious German before he awoke confused and in pain. The bleeding from his ears meant he had a concussion—a serious one—but there wasn’t much they could do for that except keep him still.

She worked quickly. Her fingers did their job with skill and speed so that she could get back to the cleanup work in the operating room.

Not ten minutes ago, Dr. Anderson had shaken his head, telling her their patient hadn’t made it. They’d tried their best to save the young American soldier, but his injuries had been too extensive.

She’d stood there, clamp in hand, unmoving.

Another life gone. Another family whose boy wouldn’t be coming home. Pain knotted her gut.

Dr. Anderson had looked at her with compassion. He was one of the few field doctors who understood the nurses’ pain when seeing the limp bodies of the soldiers being carried away.

“Change the bandages on that German brought in earlier, and then you can come back and deal with the mess,” he’d told her and then walked toward the front door, going outside for fresh air and to clear his head.

Meredith couldn’t help thinking of her brother Pete as she bit her lip and finished winding a clean bandage around the arm of the injured German. Pete was home. He was safe. She thought of another man she’d loved once, wondering if he was in harm’s way, but she quickly pushed the memory of David’s handsome face from her mind. She wouldn’t think of him now. To do so would only bring hurt, and she was carrying enough of that.

Meredith gazed down at the dark-haired man before her. His head was traumatized, and shrapnel had been dug from his arm, shoulder, and neck. His wounds weren’t any worse than many others. In time he’d recover and return to his family, who probably waited and prayed.

While it wasn’t popular to say, German mothers loved their sons as much as American mothers, she supposed. German hearts loved too.

She’d known that kind of love. She’d seen it in David’s eyes. The only thing that pushed his abandonment from her thoughts was caring for the soldiers who returned from the front lines in the ambulances’ steady flow. Her mind stayed busy doing her part in making sure those men returned home.

Home. Someday she’d return to Lafayette, Indiana. She wanted that more than anything. But since she wouldn’t be returning anytime soon, did she dare hope that the Germans wouldn’t get too close? That their American field hospital would stay out of harm’s way? And maybe, well, was it too much to wish for a little music this Christmas, singing around the piano as they always had in the Turner house?

Looking back, she couldn’t believe she’d run so far, leaving behind the family she loved. Meredith had thought she was too big for that town. She couldn’t wait to see what the expansive, wide world had for her. To find sunshine and worth. But it hadn’t worked.

Meredith shivered as a cold wind hit the window of the schoolhouse where their unit had been set up. The school had four wings, and they put them to good use as a receiving room, a shock ward, surgery, and post-op. She liked working in the post-operation room the best. Even though it tugged on her emotions, she liked being there when the soldiers awoke from surgery. She liked encouraging them, talking of home, and praying with them. She wanted to be the first friendly face they saw when they realized that the war was over for them. Because their injuries were debilitating, for most of them it meant they’d be going home.

There was also a wood-burning stove in each room. There wasn’t enough wood to keep the place much above freezing, but the walls offered some relief from the frigid chill outside.

At least it was more protection than the medical tents she’d been working in since July. The maps, posters, and children’s pictures pinned to the walls of the schoolhouse brightened her spirits. They reminded her of why she was here—who the American soldiers were fighting for.

She and the other nurses had landed on Utah Beach July 15, a month after D-Day. She’d expected to see signs of the struggle. Blood on the sand. Even though the beach was broken up, hit by war, there was no evidence of the thousands and thousands of lives lost there. What the soldiers hadn’t cleaned up, the sea had washed away.

From France, they’d moved leapfrog-style, following the movement of troops to the front line. There were three field units in the 53rd Field Hospital. Meredith was in the 3rd Unit. Soldiers with stomach and chest wounds who needed immediate care were sent to them first. And the sooner the better. Everyone called the first hour after an injury the “golden hour.” Depending on his injuries, if the field hospital could get the wounded soldier within that time frame, stabilize him, and treat him for shock, then the chance for survival was good.

Another round of artillery boomed in the distance, causing a shudder to move through the small brick school.

Meredith willed the front lines to stay far away and the supply lines to stay open. She released the breath she’d been holding. Her fingers trembled as she worked, and she wondered if she’d ever be used to war.

Footsteps sounded outside, and two ambulance drivers rushed into the hospital with an injured man. The wounded soldier shivered. His face was as pale as the snow outside.

“He’s in shock. We need plasma now!” Dr. Anderson called from across the room. He’d returned without Meredith seeing him.

Dina, one of the other nurses, rushed to assist him. They all took turns with the bad cases. Meredith was thankful it was Dina’s turn. She had cleanup to attend to. Would she be able to wipe up the spilled blood without shedding a few tears for the lost soldier this time? She doubted it.

Meredith tried not to think about that as she listened to the shuffle of nurses’ feet scurrying around the room. She finished her bandaging, said a quick prayer over the German soldier, and moved to the bucket in the corner to retrieve the mop. Thankfully someone had brought in clean water.

The last operating area waited—empty, silent. She moved toward it and with a swish of the mop started sopping up the blood. As the mop swished in a swooping pattern, she looked out the window at the mother and three children who hurried by with bundles of wood in their hands. They’d been fighting for those kids. For their freedom. The Dutch people had been under Nazi occupation for years, but the Americans had freed them. The big booms of the distant artillery and the news from the front lines that trickled down to them proved the Nazis wanted to reclaim their lost hold, but the American boys were here to make sure that wasn’t going to happen.

Meredith was witnessing history, and all the nurses were glad to be doing their part, though their part was far from easy. A few nurses had already lost their lives on the front lines. To the readers of

Stars and Stripes, they were sad stories, but to Meredith they were Francis and Betty. Friends she’d laughed with and talked late into the night with, sharing secrets and stories.

Meredith returned the mop to the bucket. As she plunged it down, the water turned red. How much blood had been spilled on foreign soil? Too much. That was why it was so important to find a way to make Christmas special for the injured. Special Christmas music—it was the one thing that wouldn’t leave her thoughts. Meredith knew how to sing a number of Christmas carols, and she was sure they’d find more talent among the other nurses and doctors. Maybe they could even practice a few new numbers to help the soldiers feel not so far from home.

In the classroom next door, Dr. Anderson’s frantic voice interrupted her hopeful thoughts. The injured soldier who’d just been brought in had been placed on the operating table, and Meredith could hear Dr. Anderson’s pleading.

“C’mon, boy. Hold on. Your mama wants you home, son . . .”