Excerpt

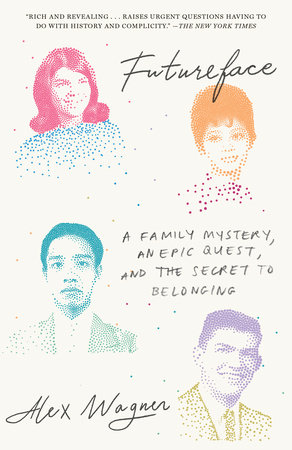

Futureface

Part I

Solitaire

Chapter One

I played a lot of solitaire growing up. I was an only child and a nerd and thus alone a lot of the time, and when I wasn’t, I was asked to mind my manners and keep quiet around the adults. For most of my adolescence, I used a weathered pack of dark blue playing cards that had the logo of the International Brotherhood of Teamsters embossed in gold on the back: a pair of horse’s heads atop a wagon wheel. Adults would see the horse head next to the Teamsters name and laugh in disbelief that a union with alleged mafia ties would have a horse’s head anywhere near its logo. I hadn’t yet seen The Godfather, and so I didn’t understand the irony, but I often pretended I did. “I know!” I would say, laughing along without understanding. I was alone, on the outside of the joke, wishing (rather pathetically) to be on the inside—where everyone else was.

The Teamsters union was where my mother worked, at the tail end of the heyday of American labor organizing, circa 1971. She had immigrated to America from Rangoon, Burma, in 1965, escaping a military dictatorship. From her initial landing pad in Washington, D.C., she went on to attend Swarthmore College, became enamored of leftist politics, and moved to Philadelphia after graduation to live in a commune with her French boyfriend and print up copies of what she described as a “socialist daily.”

The French boyfriend fell out of favor, and my mother moved back to Washington, D.C., where she found a job at the Teamsters union. That led to an interview for a job at the Alliance for Labor Action. The man who interviewed her there was my father, and from the moment they met, she couldn’t stand him. Perhaps that should have been a warning, but instead it became their meet-cute: They hated each other! And then they got married.

My father’s ancestral path to that game-changing interview began on the opposite side of the world. He was the fourth child of a rural mail carrier in northeast Iowa, the son of an Irish American mother and a father who claimed roots in Luxembourg. My dad showed an early interest in politics and, like my mother, came to Washington to do the work of liberal causes. There were no socialist dailies or French girlfriends, but he had longish hair and worked on George McGovern’s presidential campaign and knew Hunter S. Thompson. My mother and father’s remote histories intersected on a bridge of progressive bona fides and casual early seventies bohemianism. Only a few generations back, their families had been separated by oceans and mountain ranges and steppes. But in Washington, their shared values were enough to draw them close.

They were married in 1975 and several years later had their only child—me, a daughter born of an unlikely set of Burmese-Luxembourg-Irish bloodlines. Of this weird heritage, I knew little. Our Burmese story was relayed to me by my mother and grandmother, in occasional fits and starts, usually with food as the catalyst. A pot of chicken curry would summon some certain memory, which would in turn beget a snippet of family history. But only a snippet—the stories were carefully constructed, well-worn vignettes that never risked genuine revelation. Burma was kept at a safe distance from our American lives.

My father’s people were from Europe. His grandfather left the Old World sometime during the late nineteenth century, motivation unclear. I didn’t know much about his departure and why he’d made it, or even much about the place where he began: Luxembourg, a strange country about which little was discussed in my family. The one detail that slipped through was the name of his exotic-sounding hometown: Esch. And all we knew about Esch was that it sounded like the sort of place you’d want to get away from.

Luxembourg itself was largely irrelevant. For most of my adolescence, I confused it with Liechtenstein, an ant-sized country buried between Austria and Switzerland. Most everyone else also confused Liechtenstein and Luxembourg, and when forced to identify either country, would offer that it was “The smallest country in the world?” It wasn’t. My father’s mother and her family were from Ireland, but as far as American family histories went, Ireland didn’t interest me much. The good parts of being Irish had become common property, as familiar as Saint Patrick’s Day. Everyone knew Irish daughters were redheaded and pale and the boys drank too much and were always in fistfights. I was none of those things. So Luxembourg was the ancestral provenance I most frequently cited, but that was a little like being from the dark side of the moon or an island in the center of an ocean: It was like being from nowhere.

As a child I didn’t think much about the improbability of these family histories, or that I was in some way charged with their inheritance. And no one told me much about it anyway. I was mostly taught that my ancestors, whoever they were—the people thrust upon me by the random genetic alignments in the universe—should in no way affect my destiny. Anyway, wasn’t that the whole point of America? Dynasties were for the Old World. Tradition was something held aloft by Queen Elizabeth and her Easter egg–colored suits, and bloodlines were for horses and pharaohs.

America, as we had been taught, was about forward movement, not backward. Such was the proposition written in the American Gospel of Expansion and intoned to us by countless self-made politicians of every political stripe: “Go west, young man!” And by “Go west,” we really meant “Look forward—don’t worry about all that shit you’re leaving behind.”

I understood that at Christmastime my father’s side of the family enjoyed drinking a sludgy and highly alcoholic concoction known as a Tom and Jerry, that there were nuns who’d rapped his knuckles in middle school, and that in his hometown, large families were not an exception, but a given. These were my main cultural reference points for “Irish Catholic.” And they represented the extent to which my life was informed by this heritage: not in the least. They were stories recounted as asides, reminders of my father’s storybook beginning before he came east.

Elsewhere in our house, Asia was present but not entirely accounted for. When my mother went to bed each night, she knelt in prayer toward a small gold statue of the Buddha as she recited her prayers, softly and quickly. She’d touch my knee as we drove past cemeteries, and whenever I mentioned death, she would mutter in Burmese under her breath. She made me spit on my fingernails every time I trimmed them. Practically speaking, this is what it meant to be half-Burmese: a series of traditions and voodoo-like practices I didn’t really understand but nonetheless accepted.

Every April, when it was time for the annual Burmese New Year’s water festival of Thingyan, the immigrant community in and around suburban Silver Spring, Maryland, would traditionally gather in someone’s backyard. On the streets of Rangoon, men and women and children threw water at one another in celebration of the new year—and to cool off in the middle of the excruciatingly hot dry season.

But in the mid-Atlantic United States, sloshing water around on 54-degree early spring weekends was an annual torture, a trauma visited upon me and my white tights by boys, usually aged ten to twelve. Armed with plastic buckets brimming with cold water from the garden hose, the boys would unceremoniously hurl water at me, with very little mirth for the coming year. I hated it, and would have much preferred to celebrate the New Year—everybody else’s new year—with Dick Clark and the Times Square ball and a glittery, feathered tiara (for me, not Dick Clark). Each April, as I beelined back to the circle of adults giggling and clucking at my soaked clothing, I felt annoyed and angry that I had to suffer through these stupid indignities, these annual pretend celebrations of heritage and calendar.

I thought of myself as generically American, both in cultural preference (Chips Ahoy, Murder, She Wrote) and appearance (Esprit and Sebagos), but occasionally, I was reminded that how I saw myself wasn’t necessarily how everyone else saw me. As on the day when I sat at the counter of the American City Diner and the white line cook turned to ask me, while my father was in the bathroom, if I was adopted. I brushed it off, as if this were something I was asked all the time (it most certainly wasn’t), laughing to relieve him of the burden of such an awkward question, and responding, “Oh no, my mother’s just Asian!”

Moments like this were reminders that, to some people, I was not generically American. I had invested fully in the story my parents told me. I considered most everyone—white line cooks, black flight attendants, Puerto Rican teachers, whatever—American, just like me, never minding that we didn’t look alike or come from the same places. We were here! And yet the feeling was not always mutual: In the eyes of certain folks, who were universally certain white folks, I was not generically American; I was something else. If my “we” included them, theirs did not include me.

Even then, as a twelve-year-old in the diner drinking a vanilla malted, I recognized the power of this exclusivity. I was deferential to it, offering a grinning explanation as to why I didn’t look the way some line cook thought the daughter of an average white American should look, a statement that verged on an apology. The cook’s certainty over what was generically American and what was not generically American seemed to be deeply entwined with something—blood or DNA or place—that was far more definitive than the casual connections I’d forged in my life thus far. Esprit tops and Nabisco cookies were American products, but for the cook, they weren’t sufficient identifiers. I envied this sense of ownership over who was (or must be) a Typical American—his specificity regarding who belonged—even if it made me feel fairly terrible to have an identity I’d casually assumed and embodied suddenly . . . denied.

If I wanted to belong, to circumscribe my identity in some similarly definitive way, I eventually realized that the answer was not in trying to retrofit myself into the world of generically white Americana (where I would never be at home), nor did it mean full accession to the suburban Burmese exile community in Silver Spring (which seemed even more alien and had a significant language barrier to boot).

After all, neither my maternal nor paternal lines had held much sway over my life thus far—Luxembourg and Burma were about as resonant as Narnia and the North Pole. But when I considered my heritage as a single thing, rather than an either-or proposition where one was forced to toggle between Rangoon and Esch, these two poles—Burmese and Irish-German—taken together offered something entirely, definitively new. And this category of Broadly Mixed Race Heritage, this was a place I could belong!

To a certain degree, the halves themselves no longer mattered; it was almost as if they canceled each other out, and in the vacuum that created there was something new and unburdened by expectation and history. I wouldn’t be bound by stale, atavistic ideas about identity, some hokey old timer’s notion of what “regular” America looked like. That was the past! The signifiers of my tribe would be as rigorous in their inclusion as that line cook was in his exclusion: The less you fit into any one category, the more you belonged.

My thinking about this brave new identity crystalized on November 18, 1993, when the cover of Time heralded “The New Face of America,” which, kind of (if you squinted or were legally blind), looked like me.1

“Take a good look at this woman,” the headline dared the reader. “She was created by a computer from a mix of several races. What you see is a remarkable preview of . . . the new face of america.” The thrill!

Inside was a story that promised to explain “how immigrants are shaping the world’s first multicultural society.”

I was a sophomore in high school and the cover was a revelation: I was the new face of America! Somehow I was a precursor, sent from the future to show the people of America what they would all look like a few generations hence. Just as Time promised, these parents of mine—one immigrant plus the child of some immigrants—had unknowingly created the futureface.

When I found a box, in late high school, filled with my mother’s old clothes from the seventies, there was a tiny bright green T-shirt emblazoned with orange iron-on letters that spelled out rangoon ramona. It was something my father had made for my mother, based on a nickname that had been retired several anniversaries ago, but here was the perfect shirt for me, futureface. Rangoon Ramona. Who was she? It was like Clark Kent finding the S logo.

“Rangoon” was the capital of Burma, far away on the other side of the world. “Ramona” was continental, the Old World. The old European world, that is. It dawned on me—sitting on the linoleum floor of a basement redolent of wet wood and cat litter—that there was something here. I felt lucky. To be Burmese without the Irish-German half was to just be Asian. To be merely a descendant of Irish Germans was just to be white. Oh, but to be both! To be both was to be the space between them, the whole world that their stories traversed. It was to be the future.

And so here I was, in my mother’s hand-me-down rangoon ramona T-shirt, defending not one particular culture but swimming around—gloating, even—in the new thing created from the mixture of two. It seemed almost greedy. On a trip to Hawaii right before college, a local called me a “hapa.” What exactly was a hapa? “It means you’re mixed!” he said to me, and the revelation was akin to having lived your whole life thinking you were a pigeon only to find out you were a toucan. Tropical, ambiguous, exotic. Hapa.

Shortly after college, on a visit to New York, I was wearing a single feather earring and ordering a coffee when a man with a deeply cleft chin came up and asked me, with the hushed incredulity of an actor on The Bold and the Beautiful, “What’s your blood?” I responded, “O negative,” because he deserved a ridiculous answer for an absurd question . . . and then I promptly recounted the story throughout the day to anyone who would listen. “Can you believe that douchebag?” I asked my friends. They could not believe that douchebag.