Excerpt

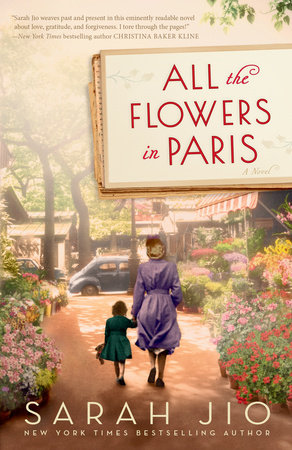

All the Flowers in Paris

CHAPTER 1

•

CAROLINE

SEPTEMBER 4, 2009

Paris, France

How could he? My cheeks burn as I climb onto my bike, pedaling fast down the rue Cler, past the street vendors with their tables lined with shiny purple eggplants and bunches of flowers, pink peonies and golden sunflowers standing at attention in tidy buckets, past Café du Monde, where I sometimes get a coffee when I’m too tired to walk to Bistro Jeanty, past an old woman walking her tiny white poodle. Despite the bright sun overhead, she pessimistically clutches a sheathed umbrella, as if at any moment the skies might open and unleash their fury.

Fury is the emotion I feel. Furious, rather. He was the last person on earth I expected or wanted to see this morning. After everything that’s happened, does he not have the decency to respect my wishes? I told him I didn’t want to see him, now or . . . ever. And yet, here he materializes, at Café du Monde of all places, smiling at me as if nothing has happened, as if . . .

I blink back tears, careful to regain my composure, the way I didn’t last night, when I threw down my napkin, shouted at him, and stormed off. A Parisian woman, in contrast, would never lose her cool like that.

While I have a lot to work on in that department, on any given day I might pass for French, at least from a distance. I look the part, more or less. Scarf tied loosely around my neck. On a bike in a dress. Blond hair swept up in a high bun. No helmet—obviously. It has taken three years to semi-master the language (emphasis on the “semi”), but it would easily take a lifetime to become adequately versed in French style.

But what does any of it matter now? Over time, Paris has become my hiding place, my cocoon, my escape from the pain of the past. I blink back tears. And now? Does he really think he can just waltz in and expect me to behave as if nothing happened? That everything should just magically go back to the way it was?

I shudder, glancing over my shoulder to make sure he isn’t following me. As far as I can tell, he’s not, and I pedal faster around the next corner, where a man in a leather jacket catches my eye and smiles as though we’ve met before. We haven’t. Saying that Frenchmen are notoriously forward is an understatement. The truth is, they believe the world, and every woman in it, should be so lucky to be graced by their special good looks, charm, and intelligence.

I’ve barely dipped my toe into the pool of French dating, and the experience hasn’t been great. There was dinner with the hairstylist, who couldn’t stop checking himself out in the mirror behind me; lunch with the artist, who suggested we go back to his apartment and discuss his latest painting, which, by chance, hung over his bed; and then the professor who asked me out last week . . . and yet I couldn’t bring myself to return his calls.

I sigh and pedal on. I am neither American nor Parisian. In fact, these days, I don’t feel as if I’m anything. I belong to no country or person. Unattached, I am merely a ghost, floating through life.

I wend past the rue de Seine, zigzagging down a lamppost-lined hill, the grandeur of the city at my back, my pale-blue sundress fluttering in the breeze as more tears well up in my eyes, fogging my view of the narrow street below. I blink hard, wiping away a tear, and the expanse of cobblestones comes into focus again. My eyes fix on an elderly couple walking on the sidewalk ahead. They are like any older French couple, I suppose, characteristically adorable in a way that they will never know. He in a sport coat (despite the humid eighty-five-degree day), and she in a gingham dress, perhaps in her closet since the afternoon she saw it in the window of a sensible boutique along the Champs-Élysées in 1953. She carries a basket filled with farmers’-market finds (I notice the zucchini). He carries a baguette, and nothing else, like a World War II–era rifle held against his shoulder, dutifully, but also with a barely detectable and oddly charming tinge of annoyance.

My mind returns to the exchange at the café, and I am once again furious. I hear his voice in my head, soft, sweet, pleading. Was I too hard on him? No. No. Maybe? No! In another life, we might have spent this evening nestled in a corner table at some café, drinking good Bordeaux, listening to Chet Baker, discussing hypothetical trips to the Greek islands or the construction of a backyard greenhouse where we would consider the merits of growing a lemon (or avocado?) tree in a pot and sit under a bougainvillea vine like the one my mom planted the year I turned eleven, before my dad left. Jazz. Santorini. Lemon trees. Beautiful, loving details, none of which matter anymore. Not in this life, anyhow. That chapter has ended. No, the book has.

How could I forgive him? How could I ever forgive him . . .

“Forgiveness is a gift,” a therapist I saw for a few sessions had said, “both to the receiver and to yourself. But no one can give a gift when she’s not ready to.”

I close my eyes for a moment, then open them, resolute. I am not ready now, and I doubt that I will ever be. I pedal on, faster, determined. The pain of the past suddenly comes into sharp and bitter focus. It stings, like a slice of lemon pressed to a wound.

I wipe away another tear as a truck barrels toward me out of nowhere. Adrenaline surges in the way it does when you’re zoning out while driving and then narrowly miss swerving into an oncoming car, or a light post, or a man walking his dog. I veer my bicycle to the right, careful to avoid a mother and her young daughter walking toward me on my left. The little girl looks no older than two. My heart swells. The sun is bright, blindingly so, and it filters through her sandy blond hair.

I squint, attempting to navigate the narrow road ahead, my heart beating faster by the second. The driver of the truck doesn’t seem to see me. “Stop!” I cry. “Arrêtez!”

I clench the handlebars, engaging the brakes, but somehow they give out. The street is steep and narrow, too narrow, and I am now barreling down a hillside with increasing speed. The driver of the truck is fiddling with a cigarette, turning it this way and that, simultaneously swerving the truck across the cobblestone streets. I scream again, but he doesn’t seem to hear. Panic washes over me, thick and overpowering. I have two choices: turn left and crash my bike straight into the mother and her little girl, or turn right and collide directly into the truck.

I turn right.

CHAPTER 2

•

CÉLINE

SEPTEMBER 4, 1943

Paris, France

“Autumn’s coming,” Papa says, casting his gaze out the window of our little flower shop on the rue Cler. Despite the blue sky overhead, there are storm clouds in his eyes.

“Oh, Papa,” I say through the open door, straightening my apron before sweeping a few stray rose petals off the cobblestones in front of the shop. I always feel bad for fallen petals, as silly as that sounds. They’re like little lost ducklings separated from their mama. “It’s only the beginning of September, my oh-so-very-pessimistic papa.” I smile facetiously. “It’s been the most beautiful summer; can’t we just enjoy it while it lasts?”

“Beautiful?” Papa throws his arms in the air in the dramatic fashion that all Frenchmen over the age of sixty do so well. I’ve often thought that there’s probably an old French law stating that if you’re an older male, you have the irrevocable right to be grumpy, cantankerous, and otherwise disagreeable at the time and place of your choosing. Papa certainly exercises this right, and yet I love him all the more for it. Grumpy or not, he still has the biggest heart of any Frenchman I’ve ever known. “Our city is occupied by Nazi soldiers and you call this summer . . . beautiful?” He shakes his head, returning to an elaborate arrangement he’s been fussing over all day for Madame Jeanty, one of our more exacting clients. A local tastemaker, and owner of one of the most fashionable restaurants in town, Bistro Jeanty, she funnels many clients to us, namely, new admissions into the high-society circle who want their dining room tables to look as grand as hers. As such, Papa and I know we can’t risk losing her business, and her demands must always be heeded, no matter how ridiculous, or how late (or early) the hour. Never too much greenery, but then never too little, either. Only roses that have been snipped that morning. Never peonies, only ranunculus. And for the love of all that is holy, no ferns. Not even a hint of them. I made that mistake in an arrangement three years ago, and let’s just say it will never happen again.

It’s funny how different a child can be from a parent. Her son, Luc, for instance, is nothing like her. We’ve known each other since secondary school, and I’ve always thought the world of him. We have dinner together each week at Bistro Jeanty, and I’ve valued our friendship, especially during this godforsaken occupation. Luc and I might have been sweethearts under different circumstances. If the world weren’t at war, if our lives had taken different paths. I’ve thought about it many times, of course, and I know he has too. The Book of Us remains a complicated story, and neither of us, it seems, knows the ending.