Excerpt

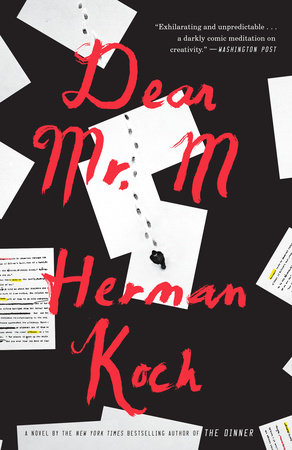

Dear Mr. M

1

Dear Mr. M,

I’d like to start by telling you that I’m doing better now. I do so because you probably have no idea that I was ever doing worse. Much worse, in fact, but I’ll get to that later on.

In your books you often describe faces, but I’d like to challenge you to describe mine. Down here, beside the front door we share, or in the elevator, you nod to me politely, but on the street and at the supermarket, and even just a few days ago, when you and your wife were having dinner at La B., you showed no sign of recognition.

I can imagine that a writer’s gaze is mostly directed inward, but then you shouldn’t try to describe faces in your books. Descriptions of faces are quite obsolete, actually, as are descriptions of landscapes, so it all makes sense as far as that goes. Because you too are quite obsolete, and I mean that not only in terms of age—a person can be old but not nearly obsolete—but you are both: old

and obsolete.

You and your wife had a window table. As usual. I was at the bar—also as usual. I had just taken a sip of my beer when your gaze passed over my face, but you didn’t recognize me. Then your wife looked in my direction and smiled, and then you leaned over and asked her something, after which you nodded to me at last, in hindsight.

Women are better at faces. Especially men’s faces. Women don’t have to describe faces, only remember them. They can tell at a glance whether it’s a strong face or a weak one; whether they, by any stretch of the imagination, would want to carry that face’s child inside their body. Women watch over the fitness of the species. Your wife, too, once looked at your face that way and decided that it was strong enough—that it posed no risk for the human race.

Your wife’s willingness to allow a daughter to grow inside her who had, by all laws of probability, a fifty-percent chance of inheriting your face, is something you should view as a compliment. Perhaps the greatest compliment a woman can give a man.

Yes, I’m doing better now. In fact, when I watched you this morning as you helped her into the taxi, I couldn’t help smiling. You have a lovely wife. Lovely and young. I attach no value judgment to the difference in your ages. A writer has to have a young and lovely wife. Or perhaps it’s more like a writer has a

right to a lovely, young wife.

A writer doesn’t

have to do anything, of course. All a writer has to do is write books. But a lovely, young wife can help him do that. Especially when that wife is completely self-effacing; the kind who spreads her wings over his talent like a mother hen and chases away anyone who comes too close to the nest; who tiptoes around the house when he’s working in his study and only slides a cup of tea or a plate of chocolates through a crack in the doorway at fixed times; who puts up with half-mumbled replies to her questions at the dinner table; who knows that it might be better not to talk to him at all, not even when they go out to eat at the restaurant around the corner from their house, because his mind, after all, is brimming over with things that she, with her limited body of thought—her limited

feminine body of thought—could never fathom anyway.

This morning I looked down from my balcony at you and your wife, and I couldn’t help but think about these things. I examined your movements, how you held open the door of the taxi for her: gallant as always, but also overly deliberate as always, so stiff and wooden, sometimes it’s as though your own body is struggling against your presence. Anyone can learn the steps, but not everyone can really dance. This morning, the difference in age between you and your wife could have been expressed only in light-years. When she’s around, you sometimes remind me of a reproduction of a dark and crackly seventeenth-century painting hung beside a sunny new postcard.

In fact, though, I was looking mostly at your wife. And again I noticed how pretty she is. In her white sneakers, her white T-shirt, and her blue jeans she danced before me the dance that you, at moments like that, barely seem to fathom. I looked at the sunglasses slid up on her hair—the hair she had pinned up behind her ears—and everything, every movement she made, spoke of her excitement at her coming departure, making her even prettier than usual.

It was as though, in the clothing she’d chosen, in everything down to the slightest gesture, she was looking forward to going where she was going. And while I watched her from my balcony I also saw, for a fleeting moment, reflected in your wife’s appearance, the glistening sand and the seawater in slow retreat across the shells. The next moment, she disappeared from my field of vision—from our field of vision—in the back of the taxi as it pulled away.

How long will she be gone? A week? Two weeks? It doesn’t matter all that much. You are alone, that’s what counts. A week ought to be enough.

Yes, I have certain plans for you, Mr. M. You may think you’re alone, but as of today I’m here too. In a certain sense, of course, I’ve always been here, but now I’m really here. I’m here, and I won’t be going away, not for a while yet.

I wish you a good night—your first night alone. I’m turning off the lights now, but I remain with you.