Excerpt

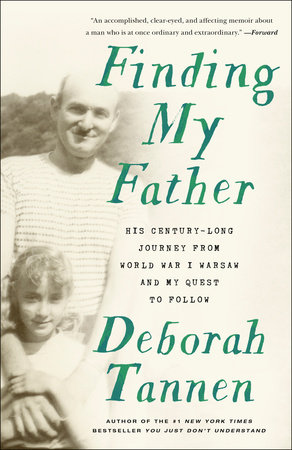

Finding My Father

Chapter OneIts Hour Come Round at LastI adored my father. He’s the parent I felt an affinity with, the one I thought understood me. I trace to him my love of words, of language, of reading, and of writing. When my father was home, he was often sitting at his desk, writing. That remained his favorite place to be, his favorite thing to do, until he died two weeks before his ninety-eighth birthday. I don’t know if I was emulating him or expressing the genes he passed on, but when I was a child, the object I loved most was an old black manual typewriter with yellowing keys rimmed in tarnished silver. I typed poems and stories—and letters to my father, telling him what happened to me during the day, often laying out grievances against my mother.

I talked to my father through letters because when I was growing up he was rarely home. The strongest presence I felt in the house was his absence. A sense of yearning for him stayed with me long after I was grown. A dream I had in my thirties was typical: I’m having a birthday party. My father is there, but he’s suspended about two feet off the floor, with his head near the ceiling. I don’t know what he’s doing up there; he doesn’t seem to be doing anything, just floating in his own world. I can’t reach him; he doesn’t seem to hear or see me. I desperately try to make contact with him, but he’s stuck up there, and I can’t get him to come down.

After my father retired at seventy, he had time to spend with me and talk to me—and during the nearly thirty years left to us before he died, he did a great deal of both. Yet I’m seeking him still. A character in a story by Ethan Canin says, of a TV show he turned on in the middle, “I have entered too late to understand.” That’s what it’s like to try to understand our parents: we came into their lives too late. But we keep trying, keep crafting our own personal creation story—maybe creation myth. By writing this book, I’m trying to figure out what happened in my father’s life before I came in. My parents both helped by living to be very old: as they aged, their internal censors fell, and they told me things about their marriage that made me question everything I’d thought about their relationship; about relationships between women and men; and about the circumstances of my birth. My father helped especially, because he was ever eager to talk about his past—and because he left me mountains of words: not only the hours and hours of conversations we had, but also stacks of letters and notes that he saved, and memories that he wrote down for me.

I think I’ve come closer to understanding my father. I know I’ve come to see that his life story, as I heard it growing up and embellished it in my mind—the creation story I’d devised for myself—was, in many ways, a myth.

*

My father’s life traces the history of the twentieth century: he was born in 1908 and died in 2006.

I’ve always been proud that my parents were born in Europe—my father in Poland, my mother in Russia. When I was a child, I thought it exotic. As I got older, I liked that it gave me a closer connection to my European roots, compared to most American Jews of my generation, whose parents were born here; it was their grandparents who came from Europe. But it wasn’t until writing this book that I understood the significance of that difference, the ways that my parents’ immigration reflects history: they came to the United States at the tail end of the massive influx that brought more than 2 million East European Jews to the United States between 1880 and 1924. The year my father came, 1920, was the last year there were few limits on immigration from Europe. The very next year the Statue of Liberty lowered her torch: in 1921 Congress imposed quotas, and in 1924—the year after my mother arrived—quotas were set so low that the doors effectively slammed shut.

My father was raised in a Hasidic household in Warsaw and had astonishingly detailed memories of life in that community before, during, and immediately after the First World War. He turned twelve two weeks after arriving in the United States with his mother and sister; his father had long since died of tuberculosis. At fourteen, my father became the family breadwinner: he quit high school and went to work in New York’s garment district. He studied high school subjects on his own; passed a law school qualifying exam; attended law school at night; earned a master’s degree in law; and passed the bar exam on the first try. But the Great Depression had descended, so he couldn’t get work as a lawyer or build up a practice without first working for little or no pay. This he could not do—not then, and not for many years after—because he was supporting first his mother and sister, then his wife and children. He was a Communist, and was investigated by the FBI; I have a copy of his file. Disillusioned with Communism, he became active in New York’s Liberal Party, a progressive third party closely tied to the garment workers’ union, and ran for City Council and for Congress on their ticket. From the time he received his law degree at twenty-one to the time he began earning a living as a lawyer at fifty, he held a dizzying number and array of jobs, including prison guard, parole officer, gun-toting alcohol tax inspector, and, from the time I was born till I was in junior high, a cutter in the garment district. After that, my father was a partner in his own law firm.

His is an American story, an immigrant story.

*

In writing this book, I’m fulfilling an assignment I gave myself more years ago than I can remember. Or maybe it’s an assignment my father gave me. A year after he retired, in 1979, he began writing down memories of his life:

This is an inauspicious spur of the moment beginning. I doubt I’ll live long enough ever to read these pages, just as I don’t expect to complete, nor even start, the myriad projects I’ve set for myself, so this effort can only be for my children or grandchildren. Maybe one of them will some day peruse these notes, or jottings, and find a nugget—one that might even be incorporated in a book (as I ventured to suggest to Deborah recently).

Reading this now, I’m caught up short: was it my father’s idea that I write this book? I was certain it was mine. And 1979? I often say I’ve been planning to write a book about my father forever, but I didn’t realize that forever goes that far back.

I find a note my father attached to a multipage dot-matrix printout of memories he’s written for me, stamped with the date Dec. 5, 1992. (He always had a date stamp on his desk, and always used it; how I wish I had done the same.) In the note, my father encourages me to write this book: “D’you have an envelope for my stuff? You know many of us take seriously your suggestion that you’ll write a booklet on the basis of my recollections after I’m gone.” My father talks to me through notes like this, and through slips of paper on which I jotted down things he said. Through one such slip of paper he tells me, “If you write it while I’m alive, you’ll have to be thinking of my feelings.”

I say to him in my mind, You’re no longer alive, but I’m still thinking about your feelings. I’m trying to understand what they were, and how they shaped your life—and mine.

I first planned to write my father’s life in the mid-1990s, while he was alive. It was going to be my next book after You Just Don’t Understand, the book that became a surprise bestseller and changed my life, and the one that followed, Talking from 9 to 5. I started interviewing him regularly, recording our conversations and writing notes, but didn’t begin shaping the material into a book. In 1995 I feared I was tempting fate by putting it off: my father was eighty-seven, and had a bad fall. Yet I went ahead and wrote two other books instead. When those were done, he was ninety-three and, amazingly, still fine. Why didn’t I count my lucky stars and start writing this book then? I think in a way I felt like Penelope, who said she’d accept her husband Odysseus’s death when she finished weaving a death shroud, but made sure she never finished it. So long as I was still gathering my father’s stories, he couldn’t die. If I were to start writing the book about him, it would be like writing his obituary, accepting, if not hastening, his death.

My father died more than a dozen years ago. The time for this book has come round at last.