Excerpt

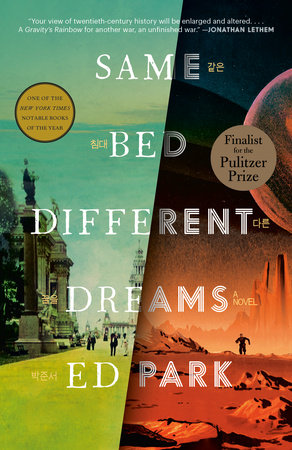

Same Bed Different Dreams

What is history?That is the question, that is the job. Might a deeper understanding of history benefit the company, or is it to be avoided at all costs? Teams are told to blue-sky it, whiteboard it, list out pros and cons. When you break the word down, what does it tell you? The Latin, from the Greek.

Three telegenic academics discuss it at an all-hands. The first speaker, an American wunderkind, sports a headset with a purple-foamed mic that resembles a levitating gumdrop on the jumbotron. “History,” she intones as she paces, “from the same Indo-European root that gave us wit.” She mimes tearing out and crumpling her notes, to signal Enough with the old ways. In the last decade, she says, history has toppled from the king of disciplines to a numbing data set: a litany of trackable moments, the realm of machines.

She stands at the lip of the stage. Everything you buy, view, read, and believe gets recorded. Where you drive, how you sleep. Lusts and peccadilloes. Mental lapses, steps climbed. Debits and credits, search terms and activity logs. Only by going off the grid can one enter true history. “Abolish every clock,” she concludes. “Go back to Day Zero.”

A concerned murmur. Is this a dig at the company and its voracious tab keeping? Or will this radical reset somehow help them do their job? The workers clap politely.

“Day Zero?” comes a coy query, from the second historian. “Hmm.”

He’s her former adviser. White hair, black eyebrows, with a mustache that splits the difference. Remaining seated, he offers a rambling anecdote by way of rebuttal. Early in his career, while engrossed in some eighteenth-century grain ledgers, he brooded over the meaning of history. One afternoon, sharpening a pencil, he received the answer, a metaphor that perfectly captured his calling. He wrote it down and continued his work amid those humble documents.

Four years passed, as he labored on the monograph he was sure would secure his reputation. Nearly finished, he prepared the coup de grâce: his shattering insight into the true nature of history. Now, alas, the full formula eluded him. After days of searching, he located the slip of paper with the aperçu at the bottom of his satchel. To his horror, a summer storm had reduced it to a blank white scrap. The more he tried recalling the words, the less sure he was about anything.

The crowd takes it all down. A cough booms through the speakers.

“My old friend asserts we should avoid metaphor when it comes to history,” sniffs the third panelist, a cheeky maverick of indecipherable ethnicity, gender, and height. “Yet the nostalgic scene he presents is itself a new metaphor, as apt and useless as all others, by his own definition. What is history, you ask? A message from a genius, ruined by the rain.”

For two hours, the three scholars spar, drawing on video games, mirror neurons, some minor works of Poe. They speak to be quoted, and the audience of employees sits rapt. For the most part. During the debate, someone secretly records a colleague pinching his own thighs, struggling to keep his eyes open—to no avail. Soon the man is snoring. Onstage, the first scholar booms, “What is history?” The subject wakes with a start, slurps back some drool.

The video gets forwarded, bcc’d, uploaded, liked. The self-pincher’s face is only half visible, but the gist is clear. As the clip makes the rounds, viewers add captions, crude animations. It becomes a sort of folk tale, bristling with embellishment. It speaks to current events, pop culture, the environment. Versions leak outside the organization: jumping borders and slipping into foreign tongues. Spin-offs exist that are not safe for work. This fading, drooling figure in the crowd is part of history, too, even if the official transcript omits the incident.

What is history?

At least for now, it’s a three-way standoff, a memory of rain, a cure for insomnia. These possibilities are duly entered into the system.

The Sins August The Jury

From a distance, the black smoking station on the white pavement in front of the Admiral Yi resembled a chess piece, whether bishop or knight, I couldn’t decide. The matter seemed crucial as I approached. My daughter, Story, would have an opinion, but of course she wasn’t with me. She was seven, and chess figured prominently in her life. During one game, in the midst of crushing my kingside defenses, she said that the bishop was worth three points, same as a knight. (Then she put me in check.) The fact surprised me. I had reckoned bishops on par with rooks, knights a step below. Then again, the bishops were yoked to their starting colors, as though you were playing checkers. Perhaps the smoking station was just a pawn after all.

Dusk hung like velvet over West Thirty-second Street, what the sign called Korea Way, though I have never heard anyone use that name. I was in the city, on a weeknight no less, a rare event for me. My family and job were upstate in Dogskill, an hour and change via Metro-North. Not so very far; still, I didn’t like visiting Manhattan. It made me miss everything too much.

My appearance was a solid for Tanner Slow: old college roommate, dispenser of numerous good deeds on my behalf, and main link to the life I’d led years ago. Tanner had worn many hats over the years. He’d been a music journalist, fired for not liking music, and briefly a literary agent—he sold my first and only book, a story collection that I couldn’t bear to look at anymore. He once ran a Tucson charity that gave bikes to the homeless, and even worked at GLOAT in the aughts, hiring me during his brief tenure. But after his father the vitamin king died and left him a zillion dollars, Tanner set up the Slow Press, devoted to his three idiosyncratic passions: political graphic novels done with woodcuts, niche cookbooks, and neglected literature in translation. Last season he’d released a revisionist account of the Haymarket Riot, a set of Malaysian curry recipes that could be done using only a rice cooker, and a collection of nature essays by “Uganda’s E. B. White.”

Tonight was simple. Tonight I’d meet Tanner Slow’s newest author, Cho Eujin, once the enfant terrible of South Korean letters. The Slow Press had signed on to bring out his oeuvre in America, and he would be a visiting lecturer at Rue University Extension Campus that fall. Tanner swore I’d like him. I couldn’t find a clear picture of Cho online, but in my mind he resembled my father, gone now over thirty years. Also slated to appear was the reclusive artist Mercy Pang, another camera avoider. My wife, Nora, was pretty sure she’d babysat for her back in the ’90s, and wanted me to take a picture so she could check.

Despite the warmth of the day, I planned to lay into a tasty bowl of seolleongtang or kalguksu, down a few OBs, and say good night to one and all in my bad Korean. I’d make sure not to get roped into a karaoke situation. I was already rehearsing my exit line, the one about having to catch the train back home out of Grand Central.

Tonight would have been a rare treat—a pleasant evening with one of my oldest friends and his latest discovery—if not for all the Asian American literati who threatened to show up as well. Poets and editors and folks associated with Rue University’s “Wildword” program. I’d mix up people’s names. I’d have nothing to say to them. I was no longer in the game.

They viewed me as a traitor. My employer, GLOAT, was so vast that it almost lost definition—they all used at least a few of its many features—but in their eyes, I’d abandoned the life of the mind to service the Almighty Algorithm.

It was true that I didn’t write anymore. For a while, I kept story notes, and one summer even wrestled a novel partway out of my skull. It had proved too unwieldy, even dangerous: a hydra that spoke in tongues. I mapped out the plot on yard-high Post-its, slapped them on the walls while I wrote. Nora likened it to the handiwork of a cop trying to outguess a serial killer, or maybe the other way around.

I didn’t write anymore. My current fictioneering was limited to bedtime tales spun out for my daughter as a sleeping aid. They involved UFOs, her chief interest besides chess. I was good at describing alien spacecrafts zipping through the clouds and the capture of curious Earthlings with a tractor beam. Once the quarry got on board, though, I went into numbing detail about the layout of the control room, lulling Story to dreamland.

I didn’t write anymore. My last jab at literary journalism had been years ago, for the late lamented Lament, which had since gone from elegant bimonthly to wisp of a quarterly to dysfunctional website, before disappearing completely. “Clean Sheets” was a jeu d’esprit about the titles I’d salvaged, to Nora’s dismay, from the basement laundry rooms of apartments where we used to live. The essay posited that these castoff libraries—self-help tomes, mouse-munched thrillers, hiking guides in foreign languages—told a building’s secret history. It was my love letter to the city; right before it came out, we moved to Dogskill. When the issue arrived, I put it directly into the recycling bin. On Friday morning I wheeled the bin to the curb, where at 9:13 a truck with a robot arm held it aloft, turned it over to release the empty bottles and printed matter, then replaced it before driving off: the quintessential suburban port de bras.