Excerpt

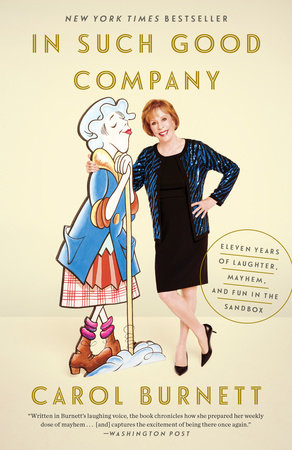

In Such Good Company

INTRODUCTION

I recently had the extreme pleasure of receiving the Screen Actors Guild Life Achievement Award, and in accepting the honor I talked about how much I loved going to the movies with my grandmother, Nanny, as a kid. My favorites were the comedies and the musicals. I think that’s when I fell in love with the idea of, someday, being a musical comedy performer. Since there wasn’t television “back in the covered wagon days,” when I was growing up, I never imagined that my dream would be realized by having my own weekly musical comedy variety show on the small screen. But that’s exactly what happened.

I’ve been thinking about that time a lot, and since my memory is pretty good, I decided to put my thoughts down on paper for anybody who might be interested in what we did and how we did it.

In doing the research for this book, I watched all 276 shows, even though at times I felt like Norma Desmond watching herself on the screen in Sunset Boulevard!

When I was watching the first few episodes, the first thing I noticed was how I looked. I laughed out loud at my various hairdos, with different shades of red, remembering that I (amateurishly) dyed my hair myself every week using Miss Clairol, because I hated to waste my time sitting in a beauty parlor.

What really stand out are the changes that evolved. Of course the hairstyles, makeup, and costumes were constantly changing. Remember, this was the late sixties into the seventies . . . bell-bottoms, miniskirts, etc. The makeup was exaggerated—heavy eyeliner and large Minnie Mouse false eyelashes . . . upper and lower! Even Bob Mackie, our brilliant costume designer, who surprised us every week with his creations, both beautiful and comedic, would admit that he missed the mark on some occasions. But they were rare.

One of the things I noticed was how I evolved over those eleven years. I went from the “zany, kooky, man-hungry, big-mouthed goofball,” which was who I had fashioned myself into during my early years, including my time as a regular on the Garry Moore television show, into a somewhat more “mature kook.”

I always loved doing the physical comedy—falling down, jumping out of windows, getting pies in the face—however, around thirty-seven, thirty-eight years old, three or four years into the show, I found myself enjoying tackling more sophisticated and complex satires and some of the sketches that had a tinge of pathos. “The Family” scenes with Eunice, Mama, and Ed always touched me deeply, because as crazy as they could get, there was always an element of reality—these were people suffering disappointment and regret, raging against fate, doing the best they could.

Naturally, there were a lot of sketches and musical numbers I had completely forgotten. Some of them made me laugh, and some, I admit, made me cringe! But overall, I was transported back to the most wonderful and pleasurable phase of my career.

What follows are many outstanding memories of what occurred during a “regular show week.” I’ll share anecdotes about our cast members, many of our guests, recurring characters, favorite movie parodies, some of the funny and off-the-cuff questions from our audience and my responses—basically how we all played together in the sandbox—hilariously—from 1967 to 1978.

Some of these stories may be familiar to those of you who know me best, but they needed to be retold in order to give you the whole picture of those eleven wonderful years!

But I’m getting ahead of myself. Let me start over at the very beginning . . .

IN THE SANDBOX

When I was growing up, theater and music were my first loves, so my original show business goals revolved around being in musical comedies on Broadway, like Ethel Merman and Mary Martin. My stage break came in the spring of 1959, when I was cast as “Winnifred the Woebegone” in the musical comedy Once Upon a Mattress, a takeoff on Hans Christian Andersen’s fairy tale “The Princess and the Pea.” It was an Off-Broadway production at the Phoenix Theatre, directed by none other than the iconic George Abbott, “Mr. Broadway” himself!

The show was originally scheduled for a limited run of six weeks, but it was so popular that it was moved to Broadway and ran for over a year. I got my wish; I was on Broadway! Because no one had expected the production to be so successful, there were numerous booking issues that caused our little show to be bounced from theater to theater—from the Phoenix to the Alvin to the Winter Garden to the Cort and, finally, to the St. James. There were a couple of jokes going around the business about the production during this period. I remember Neil Simon quipped, “It’s the most moving musical on Broadway! If you haven’t seen Once Upon a Mattress yet, don’t worry, it’ll soon be at your neighborhood theater.”

My second big break came in the fall of 1959 when I was asked to be a regular performer on The Garry Moore Show, a terrifically popular TV comedy-variety series. For almost a year, until the summer of 1960, I doubled up and did both shows. I would perform in Mattress on Tuesdays through Fridays at 8:30 p.m. and then do two shows a day on Saturdays and Sundays.

I would rehearse for Garry’s show eight to nine hours a day Monday through Friday, and then we would tape his show on Friday, in the early evening, which gave me just enough time to hop the subway and head downtown to arrive at Mattress in time for the 8:30 curtain!

I had no days off. Hey, I was young, I told myself—but evidently not that young, because one Sunday, during a matinee, I fell asleep . . . in front of the audience!

Normally, the scene involved Princess Winnifred trying her best to get a good night’s sleep on top of twenty mattresses, but she couldn’t. The mattresses were highly uncomfortable and lumpy, resulting in a very active pantomime in which I jumped up and down, pounding on the offending lumps, and finally wound up sitting on the edge of the bed wide awake, desperately counting sheep as the scene ended. Not this Sunday. As I lay there on top of twenty mattresses, I simply drifted off to dreamland. Our stage manager, who was in the wings, called, “Carol?” And then louder, “Carol!” I woke up with a start and nearly fell off the very tall bed. The audience howled, but the producers changed the schedule after that and moved the Sunday performance to Monday, so I could have Sundays off.

By that time The Garry Moore Show had switched to tape, like everyone else, but we still performed in front of a live audience as if it were a live show—no retakes, no stops. We wanted the excitement and spontaneity that went with the feeling of live theater—which was exactly what made the show so good, every Tuesday night on CBS.

The musical numbers and the writing were certainly worthy of being on the Great White Way; in fact, our junior writer was Neil Simon, whom we called “Doc.” He had worked for Sid Caesar on Your Show of Shows. It’s a little-known fact that Neil wrote Come Blow Your Horn, his first play, while he was working for Garry, who was one of his first investors!

Garry’s show was a great learning experience for me. I remember sitting around the table reading the script the week that the famous vaudeville performer Ed Wynn was the guest. Then in his seventies, he had begun his career in vaudeville in 1903 and had starred in the Ziegfeld Follies beginning in 1914. He told great stories about those days. He got on the subject of “comics vs. comedic actors.”

Garry asked him what the difference was.

“Well,” Ed said, “a comic says ‘funny things,’ like Bob Hope, and a comedic actor says things funny, like Jack Benny.”

That’s what I wanted to be . . . someone who “says things funny.”

I left Mattress in June of 1960, while I was still a regular on Garry’s show, but I really never dreamed television was going to be my “thing,” even though I found myself falling in love more and more with the small screen. Garry’s show allowed me to be different characters every week, as opposed to doing one role over and over again in the theater. In essence we mounted a distinct musical comedy revue every week—week in and week out—in front of a live studio audience, just like in summer stock.

However, I still harbored my dream of starring again on BROADWAY and being the next Ethel Merman.

CBS asked me to sign a contract with them after I had been on Garry’s show for a few seasons. The deal I was offered was for ten years, from 1962 to 1972, paying me a decent amount to do a one-hour TV special each year, as well as two guest appearances on any of their regular series. However, if I wanted to do an hour-long variety show of my own during the first five years of the contract, they would guarantee me thirty one-hour shows!

In other words, it would be my option! CBS would have to say yes, whether they wanted to or not!

They called this “pay or play” because they would have to pay me for thirty shows, even if they didn’t put them on the air. “Just push the button!” was the phrase the programming executives used. This was an unheard-of deal, but I didn’t pay much attention to it, because I had no plans to host my own show—never dreamed I’d ever want to. I was going to focus all of my energy on Broadway.

A MAN’S GAME

By 1966 I had married Joe Hamilton, who had produced Garry’s show, and we had our adorable daughter, Carrie, and another baby on the way. My Broadway career had not panned out, which was why we were in Hollywood to begin with, and I was as in demand as a carton of sour milk. We were sitting on orange crates and packing boxes in the living room of a Beverly Hills home we had somehow managed to scrape together the down payment to buy.

We had to do something to earn some money. It was the week between Christmas and New Year’s; 1967 was a few days away and our five-year deadline on the pay-or-play clause was about to expire. Joe and I looked at each other, looked around the furniture-less living room, and picked up the phone.

Mike Dann, one of the top executives at CBS in New York City, took the call and sounded happy to hear from me. He asked about our holidays and I said they had been lovely, but I was calling to “push the button” on the thirty one-hour comedy-variety shows they had promised me in my contract five years ago.

Mike honestly didn’t remember any of this. He was completely in the dark. Joe took the phone and reminded him in great detail. My guess is that more than a few lawyers were called away from their holiday parties that night to review my contract.

When Mike called the next day, he said, “Well, yes, I can see why you called, but I don’t think the hour is the best way to go. Comedy-variety shows are traditionally hosted by men: Gleason, Caesar, Benny, Berle, and now Dean . . . it’s really not for a gal. Dinah Shore’s show was mostly music.”

“But comedy-variety is what I do best! It’s what I learned doing Garry’s show—comedy sketches. We can have a rep company like Garry’s, and like Caesar’s Hour. We can have guest stars! Music!”

“Honey, we’ve got a great half-hour sitcom script that would fit you like a glove. It’s called Here’s Agnes! It’s a sure thing!”

Here’s Agnes? No thanks . . . we pushed the button.

PLAY!

CBS scheduled our show’s premiere for Monday, September 11, 1967, opposite I Spy and The Big Valley, both of which were among the top-watched shows on TV. It was pretty obvious the network didn’t think we’d last the whole season; otherwise they would have given us a more forgiving slot where we’d have had more of a chance to get some traction. In truth, we weren’t sure we’d last, either. We sighed and decided we’d at least get our thirty shows. We could start unpacking, because, for a year, the bills would get paid.

It was all a gamble, but despite everything, many of the original staff members from Garry’s show, like head writer Arnie Rosen, director Clark Jones, choreographer Ernie Flatt, lead dancer Don Crichton, and many more, took the plunge and followed us to California.

Lyle Waggoner came on board to be my handsome foil—I winced in embarrassment while rewatching the shows when I saw myself going gaga and swooning over him, which was a running gag for the first few seasons. Eventually, much to my relief, we deep-sixed the “swooning over Lyle” bit and he morphed from just being the show’s good-looking announcer to getting laughs as different nuanced characters. He turned into a very good sketch performer.

Vicki Lawrence had no professional experience when we brought her on. It was fascinating to watch her grow out of her awkward, young teenage stage and into a very clever and confident comedienne and singer/dancer.

Harvey Korman was a consummate comedic actor from the get-go, but I also saw him evolve over the years in ways that were astonishing. He never fancied himself a singer or a dancer. If our choreographer, Ernie Flatt, tried to give him a dance step to execute, he would freeze in his tracks, but if you gave Harvey the role of a dancer, he would improvise dance steps that made him look like Gene Kelly . . . well, I won’t go that far, but you’d swear the guy was born to move. It worked the same way with singing; he could sing up a storm if he was playing the part of someone who could sing!

We did a lot of movie takeoffs on the show, and I swear he seemed to channel those famous actors—Ronald Colman in our version of Random Harvest, Zachary Scott in Mildred Pierce, and who could ever forget his Clark Gable in our Gone With the Wind parody?

Tim Conway was a frequent guest in the early years and joined us every week in the ninth season! Much more about him—and the rest of our gang—later . . .

We all played together in our crazy, creative sandbox and delivered a fresh, Broadway-like musical comedy review each week, and boy did we have fun . . . for eleven years!