Excerpt

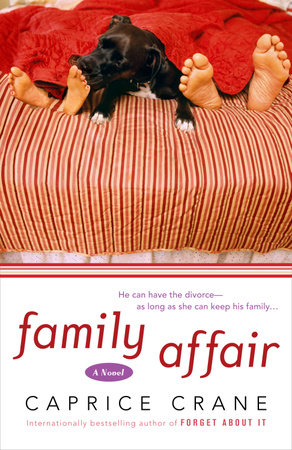

Family Affair

Layla

Eric Clapton stole Pattie Boyd from George Harrison. This is common knowledge by now. What’s less well known is that Eric Clapton stole my father from my mother. Our nuclear family was another casualty of the undying allure of sex, drugs, and platinum-selling vinyl. I used to wonder what would steal my own marital happiness.

Being named after a Clapton song is a mixed blessing. There’s the instant recognition factor, sure, but it also provides every would-be suitor a ready-made pickup line: “Layla—like the song? Were your parents listening to that song when your mom got knocked up?”

“No,” I always reply, “but wouldn’t it be cool if my name were Bruiser, ’cause then our names would rhyme!”

In seventh grade, Garret Paulson ventured a little lyrical perversion and taunted me with “Layla, you’ve got me on my knees; Layla, I’m begging, darlin’, please.” I got the last laugh, or rather, twenty or so seventh-graders at Presley Middle School did, when I swung my field-hockey stick into his groin. Talk about being on your knees. . . . Live and learn, I guess.

The name choice was my father’s doing. “Layla” was his favorite song, and my mom didn’t argue—she liked the idea of me not having a popular name. Hers is Sue, and she was surrounded by Sues all her life, constantly answering when she wasn’t called and feeling like just one among many. From the start, she wanted me to stand out—thought it was my destiny—so she went along with Layla. And dressed me in a tie-dyed Onesie.

After all the years of having my name, for some reason I still get a kick out of hearing it—almost every time. The exception is the case of its being barked at me as if I wasn’t only nine feet away from the person shouting it. This time, it’s Brett, my husband.

“Layla!” he yells, again.

I’ll tell you why I haven’t answered: because I know the acoustics of this house. I know when someone can hear you and when they can’t. I know because I live here. And because I’m not an idiot. Yet he thinks that when I call his name and he’s in the very next room—looking at a game on the TV or screwing around on his computer or whatever the case may be—I don’t know he can totally hear me. He’ll ignore me and then act all innocent. It insults my intelligence at its very core.

So I’m returning the favor. He knows damn well I can hear him. Just like he heard me this morning when I was trying to get his attention. Of course, his boy Troy Aikman was talking on the TV at the time, and I knew he’d want to watch.

My ignoring him seems petty, I realize, but he’s driven me to it. We weren’t always like this—just lately. And I know I’m the one who sounds like the jerk in this situation, but I’m only reacting to the way he’s been treating me. Which doesn’t make it better, I suppose, but it at least puts things into context.

“Could you not hear me?” Brett asks, as he storms around our place looking for something.

“What?” I say. “Did you say something?”

“I was calling you from the other room.”

“Oh, I’m sorry,” I reply, genuine as can be. “I didn’t hear you.” Just like you never seem to hear me anymore unless it’s convenient.

“Have you seen my keys?” he asks.

“I think so. In the kitchen. Or maybe on top of the hamper. Yeah, the hamper. Definitely on top of the hamper.”

He walks toward the bathroom without uttering anything resembling a thank-you, and I hear the keys jingle as he grabs them. Then I hear the front door open.

“See you at the game?” he calls out.

“Um . . .” For a split second I debate whether or not I should go. Then I consider the fact that I’ve been rather lax in my game attendance of late. And I also remember that at least I’ll have Brooke, my best friend from grade school, there to keep me company. “You bet.” •••

Brooke and I sit together at the fifty-yard line, and I chomp on stale popcorn as she rates the asses of the guys on the opposing team.

“I’m gonna give him a seven,” she says. “I think it’s hairy.”

“Gross. Why would you think that?”

“Because he’s already going bald, and hair tends to migrate. When they don’t have hair on their head, they seem to have it everywhere they don’t want it.”

“Okay,” I say. “Which begs the question, why, if it’s hairy, does he still get a seven? That’s a fairly decent score.”

“I take it back. Make it a five.” Then she points to another guy. “He gets a two. Too big. The bigger the butt, the more chances of skid marks. I’ve found they don’t wipe well when they have big butts. Too much land to cover.”

“I’m kind of horrified right now.”

“Try doing the laundry. That’s what’s horrifying.”

“Whose imaginary big-butted laundry are you doing?” I ask, because Brooke hasn’t been in a relationship for at least a year.

“Nobody’s. By choice.”

“Nice work if you can get it,” I say, as I watch Brett run along the sideline, his shock of dark hair flopping every which way. At six-two, one hundred ninety pounds, with shoulders out to here and a body in perfect fighting condition, you’d think he might be running onto the field himself to take the next handoff. And I know that nearly every female in the stadium is wondering what he looks like in those spandex shorts and compression shirts they wear at practice—I’ve heard them talking in the ladies’ room.

“How’s the coach lately?”

“He’s good,” I say, as I shove a handful of popcorn into my mouth.

“Has he even once looked up to see you in the stands?”

“He’s trying to win a game, Brooke,” I defend. “He knows I’m here.”

“He used to always look up. That’s all I’m saying.”

“Well, thank you for pointing that out to me,” I answer, as if I hadn’t noticed. I sure as hell had noticed. I don’t know if he appreciates my even coming to the games anymore. Hence my aforementioned recent lack of attendance.

I’ve done my damnedest to be a good wife—to always be supportive and make sure he knows, every day, how much I love him. I’ve spent many a day and night standing on the sidelines, wearing a hat with a large plastic beak jutting out the front, screeching and waving as I watch the team for which he’s defensive coordinator. As I watched them lose. And lose. And lose. Never mind that I don’t even really like football—I love Brett. And he loves football. He always has. I learned the basics so I could at least follow along, even though he’d still say I need Football 101. I was there cheering him on through every down of what was originally a miserable college coaching career. To me it was a failure only in name, because I was as proud of him as I would be if he’d never lost a game, even though the University of California at Culver City (UCCC) Condors were on their way to setting a new collegiate Division III record in losses that year. To his credit, even though the team had one of the lowest winning percentages ever, they had the highest graduation rate in the conference. At Brett’s insistence, he and the head coach, Frank Wells, had been stressing both unity and academics—the whole package. The school paper suggested changing the name from the Condors to the Scoreless Scholars. No one on the team thought it was funny in the least. In fact, the entire offensive line was going to trash the paper’s offices, but they all had computer lab that day.

How bad were they at that point? They’d lost their previous twenty-five games going back two and a half years, starting before Brett and Coach Wells took over. Brooke even had a running bet with me that if they ever won, she’d give me five hundred dollars. Brooke, who was working on an assistant’s salary and could barely swing her rent each month, was that sure of their suckiness. I didn’t make her pay when they finally did win—but I probably should have.

In one particularly painful game, the team gave up forty-two points—in the first quarter. Another time, they lost to a team whose bus had broken down, leaving a good half of their players stranded two hours away while the other half put together a forty-nine–zip shutout victory. I cheered for Brett’s guys throughout, and meant it. I loved being there for him, even when things looked their roughest. Maybe even especially then.

During that season, due to an early injury sidelining their field-goal kicker, Brett played a hunch and recruited the drum major from the marching band to take his place. When that guy twisted a knee, Brett and Coach Wells simply started going for it on every fourth down, whether they were on the five or the fifty, and whether they had one yard or thirty to go. The crowd loved it. Unfortunately, so did the other teams’ opposing defense. And the school paper. But that was Brett’s style, which he encouraged in Coach Wells: He was willing to take a risk and live with the consequences, no matter the opposition. That was something that only made me love him more.

Which reminds me of one particular game—the one that changed our lives, actually. With thirty seconds left, they were down by just five points and the Condors had the ball on the other guys’ seven-yard line. In two and a half years the team had never been so close late in the game. You wouldn’t know it to see the stadium seats filled with a thousand Condor faithful, enticed by the recent zany play. So what if the other ten thousand seats were empty? I alone screamed loud enough for at least a couple thousand people.

Oh, how I remember. It was a critical moment, and he clearly had something he was talking himself into, but what did Brett do? He first glanced up to search the crowd for me. My heart raced, and I met his gaze and waved like a lunatic, so proud, so in love. I could see it in his expression—he was planning something crazy. And that’s what I loved about him: his craziness. You need that touch of insanity to have the kind of chemistry we had. And win or lose, I knew we’d roll with the punches, as we’d done since the day we met in high school. The sex was better when we won, to be honest, but either way it was pretty damn good. A girl only needs to be taken on the kitchen floor, then the living-room sofa, then the dining-room table so many times. Sometimes a bed does the trick just as well.

But back to Brett’s play calling. On the key play of the key game of his early coaching career, Brett managed to talk Coach Wells into calling a triple reverse to the fullback, or something like that, something he’d been drawing up for about a month, involving three lateral passes that would leave this particular opponent’s defensive line stymied, running from side to side and gasping for air. The play was executed brilliantly—well, except for the fullback fumbling the ball out of bounds right before the goal line. The Condors lost, but the loss didn’t mean much. A lot of fans went away disappointed but not surprised, and it gave the team a chance to rally behind the hapless fullback, something that doesn’t happen enough in team sports. Somhow the close loss also gave them a vitality they hadn’t known beforehand. It was as if they gelled suddenly, and achieved the chemistry Brett and Coach Wells had been trying to foster all along.