Excerpt

Icon of Evil

Chapter 1

Rendezvous with Destiny

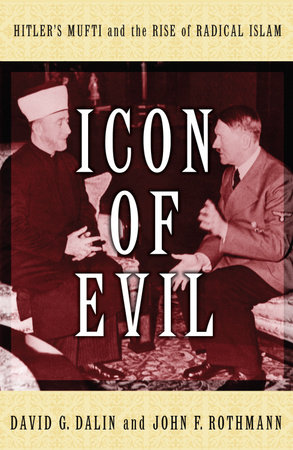

Shortly after noon on November 28, 1941, just nine days before the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, Haj Amin al-Husseini, the grand mufti of Jerusalem, left his luxurious mansion on Berlin’s fashionable Klopstock Street and was driven to the Wilhelmstrasse, the historic street on which were located most of the German government ministries. The mufti and the führer were scheduled to meet at Adolf Hitler’s private office in the Reich Chancellery.

The meeting had been scheduled for the afternoon, to accommodate Hitler’s well-known penchant for working through the night and sleeping through much of the late morning. After a short drive down the elegant Wilhelmstrasse, imperial Berlin’s old center of power, the large government Mercedes arrived at the corner of Voss-Strasse, in front of the Reich Chancellery, the opulent seat of Hitler’s government. It is plausible to assume that as the mufti’s driver turned south from Unter den Linden, which had been one of the main areas of Jewish shops in Berlin, he may have mentioned to al-Husseini, a recently arrived visitor to the German capital, that before Hitler’s assumption of power in 1933, the land under the new Reich Chancellery had belonged to the Jewish department store magnate Georg Wertheim. Wertheim had been coerced into donating his Berlin property to the new Nazi regime.

As he was escorted down a long, marble-floored corridor, alHusseini was suitably impressed by the monumental grandeur of one of the architectural wonders of the Third Reich, perhaps the greatest achievement of Hitler’s favorite architect, Albert Speer. When the führer had commissioned Speer to design and build the new Reich Chancellery in 1938, he had commented that the old building, which dated from Bismarck’s tenure in the 1870s, was “fit for a soap company” and was not suitable as headquarters of the German Reich. Speer was to create an edifice of “imperial majesty,” an imposing building with grand halls and salons. Al-Husseini was driven through the Court of Honor, the building’s main entrance, ascended an outside staircase, and approached the visitors’ elaborately ornate reception room, immediately adjacent to Hitler’s personal office. As the mufti neared the reception room, he passed through a round room with domed ceiling and a gallery 480 feet long, the exquisitely furnished mirrored gallery that Hitler had praised as surpassing the famous Hall of Mirrors at the Palace of Versailles. It boasted a length of nearly 1,200 feet, and its floor and walls were lined with dark red marble. Hitler’s immensely spacious private office and study, measuring nearly 4,500 square feet, was located immediately to its side.

Following his arrival in Berlin three weeks earlier, rapturous crowds had hailed the mufti as the führer of the Arab world. The week before his meeting with Hitler, al-Husseini had been honored at a reception given by the Islamische Zentralinstitut, a German-Islamic institute recently established in Berlin. As the mufti was driven down the Wilhelmstrasse, adoring crowds of Palestinian Arab expatriates lined the streets to cheer and pay homage to their revered leader, the

Grossmufti von Jerusalem.

Hitler regarded the mufti with both deference and respect. With the possible exception of King Ibn Saud of Saudi Arabia, al-Husseini was the most eminent and influential Islamic leader in the Middle East. The mufti, unlike Ibn Saud, was a trusted supporter of Hitler’s Germany, a man upon whom the Nazis could always rely.

The mufti began by thanking the führer for the great honor he had bestowed by receiving him. In his effort to both flatter his host and solicit his patronage and support, the mufti told Hitler that he “wished to seize the opportunity to convey to the Fuhrer of the Greater German Reich, admired by the entire Arab world, his thanks for the sympathy he had always shown for the Arab and especially the Palestinian cause. . . . The Arab countries were firmly convinced that Germany would win the war and that the Arab cause would then prosper.” The Arabs, the mufti assured his host, “were Germany’s natural friends because they had the same enemies as had Germany, namely the English, the Jews and the Communists. They were therefore prepared to cooperate with Germany with all their hearts and stood ready to participate in the war, not only negatively by the commission of acts of sabotage and the instigation of revolutions, but also positively by the formation of an Arab Legion. The Arabs could be more useful to Germany as allies than might be apparent at first glance, both for geographical reasons and because of the suffering inflicted upon them by the English and the Jews.”

The mufti’s objectives were far-reaching. He wanted to terminate Jewish immigration to Palestine, but he also hoped to help lead a holy war of Islam in alliance with Germany, a jihad that would result in the extermination of the Jews.

As al-Husseini would write in his memoirs: “Our fundmental condition for cooperating with Germany was a free hand to eradicate every last Jew from Palestine and the Arab world. I asked Hitler for an explicit undertaking to allow us to solve the Jewish problem in a manner befitting our national and racial aspirations and according to the scientific methods innovated by Germany in the handling of its Jews. The answer I got was: ‘The Jews are yours.’ ”

To the mufti’s delight, the führer responded with a strong and unequivocal reaffirmation of his anti-Jewish position and of his support for the radical Arab cause, assuring the mufti that he was fully committed to pursuing a war of extermination against the Jews and to actively opposing the creation of a Jewish national home in Palestine. As the mufti would recount after their meeting, Hitler had assured him that “Germany was resolved, step by step, to ask one European nation after the other to solve its Jewish problem, and at the proper time direct a similar appeal to non-European nations as well. Germany’s objectives would then be solely the destruction of the Jewish element residing in the Arab sphere under the protection of British power [in Palestine].” In that hour, the führer assured al-Husseini, the mufti would become the most powerful leader in the Arab world.

For the forty-six-year-old mufti, this meeting with the führer was his rendezvous with destiny. Haj Amin al-Husseini had been preparing for this moment for much of his adult life. He had gone to the Reich Chancellery to convince Adolf Hitler of his total dedication to the Nazi goal of exterminating the Jews. The führer had instantly embraced him, eagerly welcoming al-Husseini as his ally and collaborator

At the conclusion of their ninety-five-minute meeting, the mufti could reflect with great satisfaction on what he had achieved: Only three weeks after his arrival in Berlin on November 7, the mufti’s dream of a more formal alliance between radical Islam and Hitler’s Germany had become a reality.

As the mufti stood up to leave, he and the führer embraced and shook hands. It was a handshake, each believed, that would change the world.