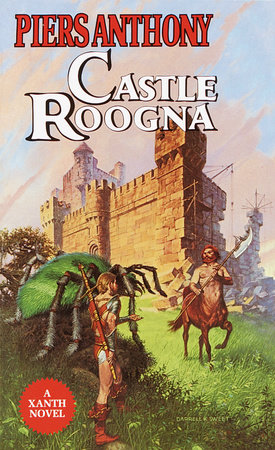

Excerpt

Castle Roogna

Chapter 1. Ogre

Millie the ghost was beautiful. Of course, she wasn’t a ghost any more, so she was Millie the nurse. She was not especially bright, and she was hardly young. She was twenty-nine years old as she reckoned it, and about eight hundred and twenty-nine as others reckoned it: the oldest creature currently associated with Castle Roogna. She had been ensorceled as a maid of seventeen, eight centuries ago, when Castle Roogna was young, and restored to life at the time of Dor’s birth. In the interim she had been a ghost, and the label had never quite worn off. And why should it? By all accounts she had been a most attractive ghost.

Indeed, she had the loveliest glowing hair, flowing like poppycorn silk to the dimpled backs of her … knees. The terrain those tresses covered in passing was—was—how was it that Dor had never noticed it before? Millie had been his nurse all these years, taking care of him while his parents were busy, and they tended to be busy a great deal of the time.

Oh, he understood that well enough. He told others that the King trusted his parents Bink and Chameleon, and anyone the King trusted was bound to be very busy, because the King’s missions were too important to leave to nobodies. All that was true enough. But Dor knew his folks didn’t have to accept all those important missions that took them all over the Land of Xanth and beyond. They simply liked to travel, to be away from home. Right now they were far away, in Mundania, and nobody went to Mundania for pleasure. It was because of him, because of his talent.

Dor remembered years ago when he had talked to the double bed Bink and Chameleon used, and asked it what had happened overnight, just from idle curiosity, and it had said—well, it had been quite interesting, especially since Chameleon had been in her beauty stage, prettier and stupider than Millie the ghost, which was going some. But his mother had overheard some of that dialogue, and told his father, and after that Dor wasn’t allowed in the bedroom any more. It wasn’t that his parents didn’t love him, Bink had carefully explained; it was that they felt nervous about what they called “invasion of privacy.” So they tended to do their most interesting things away from the house, and Dor had learned not to pry. Not when and where anyone in authority could overhear, at any rate.

Millie took care of him; she had no privacy secrets. True, she didn’t like him talking to the toilet, though it was just a pot that got emptied every day into the back garden where dung beetles magicked the stuff into sweet-smelling roses. Dor couldn’t talk to roses, because they were alive. He could talk to a dead rose—but then it remembered only what had happened since it was cut, and that wasn’t very much. And Millie didn’t like him making fun of Jonathan. Apart from that she was quite reasonable, and he liked her. But he had never really noticed her shape before.

Millie was very like a nymph, with all sorts of feminine projections and softnesses and things, and her skin was as clear as the surface of a milkweed pod just before it got milked. She usually wore a light gauzy dress that lent her an ethereal quality strongly reminiscent of her ghosthood, yet failed to conceal excitingly gentle contours beneath. Her voice was as soft as the call of a wraith. Yet she had more wit than a nymph, and more substance than a wraith. She had—

“Oh, what the fudge am I trying to figure out?” Dor demanded aloud.

“How should I know?” the kitchen table responded irritably. It had been fashioned from gnarled acorn wood, and it had a crooked temper.

Millie turned, smiling automatically. She had been washing plates at the sink; she claimed it was easier to do them by hand than to locate the proper cleaning spell, and probably for her it was. The spell was in powder form, and it came in a box the spell-caster made up at the palace, and the powder was forever running out. Few things were more annoying than chasing all over the yard after running powder. So Millie didn’t take a powder; she scrubbed the dishes herself. “Are you still hungry, Dor?”

“No,” he said, embarrassed. He was hungry, but not for food. If hunger was the proper term.

There was a hesitant, somewhat sodden knock on the door. Millie glanced across at it, her hair rippling down its luxuriant length. “That will be Jonathan,” she said brightly.

Jonathan the zombie. Dor scowled. It wasn’t that he had anything special against zombies, but he didn’t like them around the house. They tended to drop putrid chunks of themselves as they walked, and they were not pretty to look at. “Oh, what do you see in that bag of bones?” Dor demanded, hunching his body and pulling his lips in around his teeth to mimic the zombie mode.

“Why, Dor, that isn’t nice! Jonathan is an old friend. I’ve known him for centuries.” No exaggeration! The zombies had haunted the environs of Castle Roogna as long as the ghosts had. Naturally the two types of freaks had gotten to know each other.

But Millie was a woman now, alive and whole and firm. Extremely firm, Dor thought as he watched her move trippingly across the kitchen to the back door. Jonathan was, in contrast, a horribly animated dead man. A living corpse. How could she pay attention to him?

“Beauty and the beast,” he muttered savagely. Frustrated and angry, Dor stalked out of the kitchen and into the main room of the cottage. The floor was smooth, hard rind, polished until it had become reflective, and the walls were yellow-white. He banged his fist into one. “Hey, stop that!” the wall protested. “You’ll fracture me. I’m only cheese, you know!”

Dor knew. The house was a large, hollowed-out cottage cheese, long since hardened into rigidity. When it had grown, it had been alive; but as a house it was dead, and therefore he could talk to it. Not that it had anything worth saying.

Dor stormed on out the front door. “Don’t you dare slam me!” it warned, but he slammed it anyway, and heard its shaken groan behind him. That door always had been more ham than cheese.

The day outside was gloomy. He should have known; Jonathan preferred gloomy days to come calling, because they kept his chronically rotting flesh from drying up so quickly. In fact, it was about to rain. The clouds were kneading themselves into darker convolutions, getting set to clean out their systems.

“Don’t you water on me!” Dor yelled into the sky in much the tone the door had used on him. The nearest cloud chuckled evilly, with a sound like thunder.

“Dor! Wait!” a little voice called. It was Grundy the golem, actually no golem any more, not that it made much difference. He was Dor’s outdoor companion, and was always alert for Dor’s treks into the forest. Dor’s folks had really fixed it up so he would always be supervised—by people like Millie, who had no embarrassing secrets, or like Grundy, who didn’t care if they did. In fact Grundy would be downright proud to have an embarrassment.

That started Dor on another chain of thought. Actually it wasn’t just Bink and Chameleon; nobody in Castle Roogna cared to associate too closely with Dor. Because all sorts of things went on that the furniture saw and heard, and Dor could talk to the furniture. For him, the walls had ears and the floors had eyes. What was wrong with people? Were they ashamed of everything they did? Only King Trent seemed completely at ease with him. But the King could hardly spend all his time entertaining a mere boy.

Grundy caught up. “This is a bad day for exploring, Dor!” he warned. “That storm means business.”

Dor looked dourly up at the cloud. “Go soak your empty head!” he yelled at it. “You’re no thunderhead, you’re a dunderhead!”

He was answered by a spate of yellow hailstones, and had to hunch over like a zombie and shield his face with his arms until they passed.

“Be halfway sensible, Dor!” Grundy urged. “Don’t mess with that mean storm! It’ll wash us out!”

Dor reluctantly yielded to common sense. “We’ll seek cover. But not at home; the zombie’s there.”

“I wonder what Millie sees in him,” Grundy said.

“That’s what I asked.” The rain was commencing. They hurried to an umbrella tree, whose great thin canopy was just spreading to meet the droplets. Umbrella trees preferred dry soil, so they shielded it against rain. When the sun shone, they folded up, so as not to obstruct the rays. There were also parasol trees, which reacted oppositely, spreading for the sun and folding for the rain. When the two happened to seed together, there was a real wilderness problem.