Excerpt

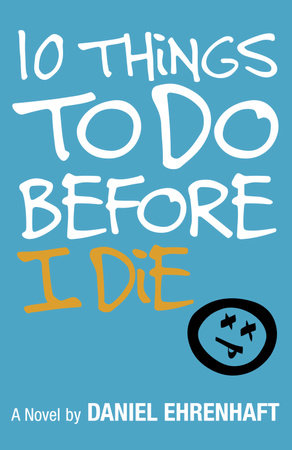

10 Things to Do Before I Die

Prologue: The Story of My Death

My name is Ted Burger. I am sixteen years old. I am an only child. I live in New York City.

I will not live to see seventeen.

What else? Let’s see. . . . My voice is pretty deep but it squeaks sometimes, like an old rusty bicycle. I have curly brown hair. “Brillo pad hair,” in my best friend Mark’s words. I am tall and skinny. My fingers are, too. They look like twigs. “Musician’s fingers,” says my guitar teacher, Mr. Puccini. (Translation: “Girlie fingers.”) I’m good at blowing stuff off. I have a hard time admitting certain things to myself. According to my parents, I have a “nutty, Borscht Belt sense of humor!” (I include the exclamation point because they tend to speak at a high-pitched volume.) What they mean is that I’m a third-rate clown, but they aren’t really ones to talk.

This is the story of my death.

It starts the way all my stories do, as a bad joke whose tragic punch line somehow ends up signifying my whole life. Or death, in this case. Ha! Ha . . . ha . . . okay, maybe my parents are right. Maybe I am a clown. I don’t have the greatest comic timing. I rarely instigate–bad things simply happen to me. Pie-in-the-face sorts of things. But don’t just take my word for it. Consider the fortune I received on my sixteenth birthday (ironically, my last birthday ever, although I didn’t know it at the time) when my parents took me to the Hong Phat Noodle House–and I swear I am not making this up:

You will never have much of a future if you look

for it in a cookie at a Chinese Restaurant. J

My mom’s fortune promised a lifetime of infinite happiness. My dad’s, a lifetime of wealth and fulfillment. When I complained to the waiter about mine, he told me that I should be pleased. “It’s true, young man,” he said with a smile. “One should never look for one’s destiny in a dessert item. One should look for it in experience.”

I agreed, sure–but deep down, I still felt sort of gypped. I asked for another one. He refused. Hong Phat policy is one fortune cookie per customer, period.

The real punch line is that I don’t even like Chinese food all that much. I like french fries. But my parents forced me to go there because they said that I needed to learn how to use chopsticks. “It’s a skill that will make you part of an important demographic, dear!” Mom insisted. That’s a direct quote. To this day, I have no idea what she means. (I never learned how to use chopsticks, either.) My parents work together at the same advertising firm, so they talk a lot about stuff like “important demographics!” It’s pretty much all they talk about. Maybe one day I will understand their baffling pronouncements. I would if I weren’t doomed to an early grave, that is.

Speaking of which, the story of my death also starts at a restaurant. It starts at the Circle Eat Diner with Mark and his girlfriend, Nikki. I can’t imagine it starting any other way. Everything starts at the Circle Eat Diner with Mark and Nikki, at least everything that matters . . . everything that happens during those sublime, BS-filled hours when the three of us laugh and rant and eat, the hours just after school and before I have to run back home to Mom and Dad.

Okay, that’s an exaggeration. I rarely have to run home to Mom and Dad. They aren’t around very often. They take a lot of business trips. All of which is a long way of saying that I spend more time hanging out at the Circle Eat Diner with Mark and Nikki than I probably should.

Much more.

You’ll see what I mean shortly. The story of my death has a very dramatic, pie-in-the-face beginning.

A Very Active Inner Life

Spring break has just started. No classes for a whole week! Woo-hoo! It’s one of those rare gorgeous afternoons in Manhattan when the sky is swimming-pool blue and the breeze is crisp. There’s no humidity at all.

Freedom! the day seems to shout. Rock and roll!

Well, the day might seem to shout that if I were outside. Inside the Circle Eat Diner, the day doesn’t seem to shout anything. It stinks of grease. The three of us are huddled over the remnants of a burger, fries, and pickle. We pretty much order the same meal every time: Circle Eat #5, the Burger/Fries Combo. I eat the fries. Mark eats the burger. Nikki eats the pickle. The way Mark and Nikki are slouched across from me in the booth, they look more like a pair of models than a real-life couple–rail thin, dark, unblemished . . . poster children for the wonders of the #5 diet.

Mark’s brown hair is a mess. His ratty T-shirt bears the logo give this dawg a bone. His brown eyes are wild. They’re always wild. This stems from a belief he’s had since he was a little kid that something bizarre and miraculous could occur at any moment–a giant-squid attack, the Rapture–and when it does, it will require his personal involvement in some way. So he’s perpetually on guard.

I envy him for this. I always have. He’s never bored.

Nikki is hardly ever bored, either, but for less delusional reasons. She’s got a very active inner life. This I can relate to. She’s constantly turning everything over in her mind–every event and conversation, no matter how trivial–and milking it for its hidden wisdom. You can tell from the way she listens, from the way she looks you in the eye . . . you can even tell from how she dresses: mostly in black. With Nikki, blackness doesn’t have an agenda. She isn’t trying to play the role of a misunderstood hipster or a sullen goth. She isn’t trying to fit in with any crowd, either. (To be honest, the three of us don’t really belong to any crowd. Not unless you include the other people who hang out in the Circle Eat Diner all the time, like Old Meatloaf Lady and Guy with Crumbs in His Beard.) Nikki just doesn’t put a whole lot of thought into her wardrobe. She’s got too much else going on inside. Once she told me that the only reason she dresses in black is so her clothes will match her hair. I loved that.

Her eyes are what really tell the story, though. They’re like onyx, calm to the point of being alien: the eyes of the extraterrestrials you see in UFO documentaries. They radiate that same mysterious, hypnotic “we-come-in-peace” vibe, even when she’s joking around or scheming.

Funny: I probably think more than Nikki does about the way she looks. Ha! Not that I’d ever admit that to her. I definitely wouldn’t admit it to Mark. I have a hard enough time admitting it to myself.