Excerpt

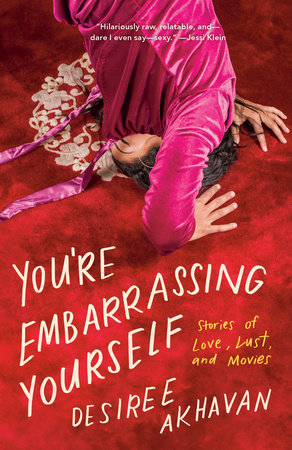

You're Embarrassing Yourself

The BeastRemember Hot or Not? It was one of the most highly trafficked websites of the early aughts. The name pretty much says it all. People uploaded photos of themselves, and users would vote: hot or not. Back then, we had a huge Dell desktop that lived in my brother Ardavan’s room, and before I could even touch it I’d have to hassle my mom to get off the phone to free up the line. Then came the process of logging on to the internet, which had a soundscape that, to this day, elicits a Pavlovian response of making my heart race in anticipation. At the time, the very existence of the internet was surreal and a bit exhilarating. I chose to use my first precious hours with it doomscrolling HotorNot. I was there to train my eye, and as I did a pattern emerged: skinny symmetrical white girls in bikinis = hot, the rest of us = not.

When I was fourteen, someone created a website where you could vote for the hottest girl at my school. I went to an elite New York City private school that took itself so seriously that when you were asked where you went to school, you’d watch yourself stiffen with a pseudo-humble Maybe you’ve heard of it? People in New York knew about Horace Mann. It was both famous and infamous, and I couldn’t decide if I should be proud or horrified.

To explain why Horace Mann was what it was, I need to set the scene. New York City sells itself as a haven for weirdos: inclusive and radical. It’s not. You have to be a certain kind of hot, rich, and successful to play—the rest of us are just extras. It’s a city built on hierarchies with a small town’s penchant for gossip. People make the pilgrimage to New York because they believe, deep in their bones, that they might be the very best at something. In turn, the city remains in a constant state of flux, perpetually measuring exactly who and what is “the best.” There’s always a best neighborhood, a best handbag, a best restaurant, a best play, and so of course the schools were measured up against one another and it was agreed by many that Horace Mann was the best of the best. Or at least that’s what our parents told themselves to justify the exorbitant tuition fees.

The students didn’t just live on Park Avenue; they lived in penthouses on Park Avenue, where the elevator doors open up into the living room. Many parents fell into the category of “New York famous,” which means profiled in the Times, but nobody outside the Citarella delivery zone has ever heard of you. Renée Fleming famous. It was shockingly overpriced, shockingly elite, shocking for about forty-seven other reasons, like the molestation of teen boys by an Austrian choir conductor who’d strut through the halls like he was Mick Jagger.

My parents put every cent they had into sending my brother and me to the best. They even took out a third mortgage on their house to make it happen. Having moved to America from Iran not knowing much about the country, the people, or the rules, they were confident that the strongest advantage they could offer was to send us to the same school as the children of the richest and most powerful, so we could mingle with them and then morph into exemplary American versions of ourselves. It’s a strategy that worked for my brother, Ardavan, who was academically gifted and disciplined. I don’t know if he mingled with the spawn of the New York elite socially, but he definitely excelled among them and adopted a sense of rigid perfection that continues to elude me. From Horace Mann he went on to Columbia University, then the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, and is currently one of the country’s leading pediatric urological surgeons.

I was never sure if I’d be able to return on that investment. For me, unlike my brother, Horace Mann didn’t make sense. It was a place for future investment bankers, doctors, lawyers, politicians, and trophy wives. Your currency lay in being the richest, the smartest, and (duh) the hottest, which of course is true of every school, but we were all high off our own farts, so of course we would go and make our own version of HotorNot.

I say “we,” but I shouldn’t. It wasn’t just that I didn’t belong. “Not belonging” is too passive. You can not belong and still function in a place. I was a different species from the rest of them. At fourteen, I had exactly one friend: Nina Klein, a high-strung, straight-A parent pleaser and competitive gymnast who taught me that grapes have ten calories apiece. Every day we’d eat lunch in the girls’ locker room so we’d be early for gym. You know, the way cool kids do.

I knew I wouldn’t be on the Hottest Girls at Horace Mann website, but that didn’t stop me from checking it every time I was within twenty feet of a computer. Knowing you’re not part of the conversation doesn’t stop you from wanting to eavesdrop and then mold yourself in the image of those who are, obsessing over every detail of their face, body, and wardrobe, scanning to see what you can copy in the hope of dragging yourself a little closer to the heart of it. I felt compelled to track who was winning the Hottest Girls at Horace Mann as if it were the presidential primary.

One day I got an email from an address I didn’t recognize. Inside was a link and nothing else. The link led me to a site with the header “The Ugliest Girls at Horace Mann.” The layout was exactly like its sister site, only next to the names were adorable nicknames like “the Slut,” “the Bitch,” “Butterface.” Most of the girls listed were actually pretty popular and conventionally hot, so I got the sense the site was an inside joke made to settle a vendetta. But then I saw my own name. Next to it, “the Beast.”

I knew I was going to be on that site the minute I saw “Ugliest.” I knew it instinctively, the way I knew liver would taste mealy, like an overripe tomato, before it ever touched my tongue. My name earned a whopping forty-two votes, while the others had two or three each. There’s no way the creators had a vendetta to settle with me. Eating lunch alone with Nina Klein in the girls’ locker room meant sidestepping vendettas. It was undeniable: I was the only person on the list who’d made it there because she was legitimately ugly. Not a bitch; a beast.

You know when something bad happens, worse than your worst nightmare, and the pure drama of it fills you with a weird sense of satisfaction? Satisfaction laced in endorphins. There was something almost euphoric about the sheer intensity of seeing my name on that website.

I felt starstruck, knowing I was watching a seminal life moment take shape before my eyes, as I refreshed the page every thirty seconds to watch my votes go up. Starstruck plus nostalgic for the life I’d been living an hour earlier, before I’d gotten the email. I’d always had a suspicion, but now I had empirical proof: I was the Ugliest.

I’d started to get the sense I might be ugly around eleven, when adults began offering up unsolicited hair, diet, exercise, and plastic surgery advice. It was about that time that I learned what “hot” was, and how it seemed to be the price of admission if you were a girl. Any woman who didn’t classify as hot was automatically relegated to being the butt of the joke. Or at least that’s what I’d gleaned from Howard Stern, who spoke on the matter for ninety minutes straight each morning, blasting through the bus speakers on the way to school.

But it wasn’t just Howard; it’s in my blood. Iranians are spectacularly superficial. Presentation is everything. We subscribe to a “more is more” aesthetic: full face of makeup to go to the grocery store. We’re serving baroque, air-kisses on both cheeks, grass-is-greener-on-my-side realness. You can’t drive home from a party without going through a full breakdown of who got fat and who got old, like Mom and Dad are Joan Rivers’s Fashion Police and you’re their backseat studio audience.