Excerpt

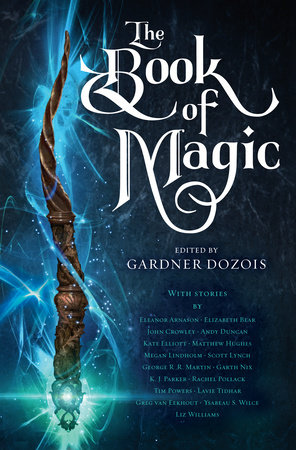

The Book of Magic

Sorcerer, witch, shaman, wizard, seer, root woman, conjure man . . . the origins of the magic-user, the-one-who-intercedes-with-the- spirits, the one who knows the ancient secrets and can call upon the hidden powers, the one who can see both the spirit world and the physical world, and who can mediate between them, go back to the beginning of human history—and beyond. Fascinating traces of ritual magic have been unearthed at various Neanderthal sites: the ritual burial of the dead, laid to rest with their favorite tools and food, and sometimes covered with owers; a low-walled stone enclosure containing seven bear heads, all facing forward; a human skull on a stake in a ring of stones . . . Neanderthal magic.

A few tens of thousands of years later, in the deep caves of Lascaux and Pech Merle and Rougnac, the Cro-Magnons were practicing magic too, perhaps learned from their vanishing Neanderthal cousins. Deep in the darkest hidden depths of the caves at La Mouthe and Les Combarelles and Altamira, in the most remote and isolate galleries, the Cro-Magnons lled wall after wall with vivid, emblematic paintings of Ice Age animals. There’s little doubt that these cave paintings—and their associational phenomena: realistic clay sculptures of bison, carved ivory horses, the enigmatic “Venus” gurines, and the abstract and inter-lacing paint-outlined human handprints known as “Macaronis”—were magic, designed to be used in sorcerous rites, although how they were meant to be employed may remain forever unknown. These ancient walls also give us what may be the very first representation of a wizard in human history, a hulking, shaggy, mysterious, deer-headed gure watching over the bright, at, painted animals as they caper across the stone.

So Magic predates Art. In fact, Art may have been invented as a tool to express Magic, to give Magic a practical means of execution—to make it work. So that if you go back far enough, artist and sorcerer are indistinguishable, one and the same—a claim that can still be made with a good deal of validity to this very day.

Stories about magic go back a similar distance, probably all the way back to when Ice Age hunters huddled around a fi re at night, listening to the beasts who howled in the inky blackness around them. By the time that Homer was telling stories to reside audiences in Bronze Age Greece, the tales he was telling contained recognizable fantasy elements—man-eating giants, spells and counterspells, enchantresses who turned men into swine—that were probably recognized as fantasy elements and responded to as such by at least the more sophisticated members of his audience. By the end of the eighteenth century, something recognizably akin to modern literary fantasy was beginning to precipitate out from the millennia-old body of oral tradition—folk tales, fairy tales, mythology, songs and ballads, wonder tales, travelers’ tales, rural traditions about the Good Folk and haunted standing stones and the giants who slept under the countryside— first in the form of Gothic stories, ghost stories, and Arabesques, and later, by the middle of the next century, in a more self-conscious literary form in the work of writers such as William Morris and George MacDonald, who reworked the subject matter of the oral traditions to create new fantasy worlds for an audience sophisticated enough to respond to the fantasy elements as literary tropes rather than as fearfully regarded, half-remembered elements of folk beliefs—people who were more likely to be entertained by the idea of putting a saucer of milk out for the fairies than to actually do such a thing.

By the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, most respectable literary gures—Dickens, Twain, Poe, Kipling, Doyle, Saki, Chesterton, Wells—had written fantasy in one form or another, if only ghost stories or Gothic stories, and a few, like orne Smith, James Branch Cabell, and Lord Dunsany, had even made something of a specialty of it. But as World War II loomed ever closer over the horizon, fantasy somehow began to fall into disrepute, increasingly being considered as unhip, “anti-modern,” non-progressive, socially irresponsible, even déclassé. By the sterile and unsmiling fties, very little fantasy was being published in any form, and, in the United States at least, fantasy as a genre, as a separate publishing category, did not exist.

When the last Ice Age started, and the glaciers ground down from the north to cover most of the North American continent, thousands of species of plants and trees, as well as the insects, birds, and animals associated with them, retreated to “cove forests” in the south, in what would eventually come to be called the Great Smoky Mountains; in those cove forests, they waited out the long domain of the ice, eventually moving north again to recolonize the land as the climate warmed and the glaciers retreated. Similarly, the lowly genre fantasy and science fiction magazines—Weird Tales and Unknown in the thirties and forties, the Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, Fantastic, and the British Science Fantasy in the fties and sixties—were the cove forests that sheltered fantasy during its long retreat from the glaciers of social realism, giving it a refuge in which to endure until the climate warmed enough to allow it to spread and repopulate again.

By the midsixties, largely through the e orts of pioneers such as Don Wollheim, Ian and Betty Ballantine, Don Benson, and Cele Goldsmith, fantasy had begun tentatively to emerge from the cove forests. And after the immense success of J. R. R. Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings trilogy, the first American publishing line devoted to fantasy, the Bal-lantine Adult Fantasy line, was established. It would be followed by others in the decades to come, until by the current day fantasy is a huge, diverse, and commercially successful genre, one which has diversified into many different types: sword & sorcery, epic fantasy, high fantasy, comic fantasy, historical fantasy, alternate world fantasy, and others.