Excerpt

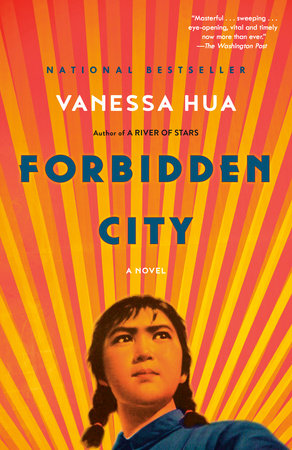

Forbidden City

Chapter 1The Party official arrived in early summer, the rumble of his jeep echoing along the rutted road. Vehicles didn’t often travel through our narrow valley, still as remote as in the days when news of an emperor’s passing arrived years afterward. I leaned on my hoe, my shoulders aching. Beside me, my two sisters had also stopped working, listening until the sound drew so close that we ran in from the fields, joining the shouts and cries of excitement.

We halted at the sight of the jeep parked in the plaza, its red flags rippling with importance on the hood. The official spoke with the headman, who pointed at a neighbor, at me, at each girl in the cultural work troupe, and gestured to a spot by the acacia tree.

“Line up. Quickly, now. Don’t keep Secretary Sun waiting,” the headman barked. He had a squat neck and a body powerful in its flab. He was curt as usual, but seemed apprehensive, shifting around on his feet. As I took my place, my blood jittered.

A dozen of us performed patriotic songs and skits on festival days. With few entertainments in the village, we always drew an audience, but we hardly seemed worthy of a Party official.

Secretary Sun had the look of a serpent, with high cheekbones and hooded eyes. He carried himself with a disciplined air, all tucks and polish. His thick black hair glinted gold, then red-brown in the sunlight.

I tried not to fidget. Perhaps he wanted to consider our troupe for a special performance in the city? Or maybe he was checking whether the lessons from the capital had made their way here.

My father, sitting beneath the acacia, tipped the brim of his hat at me, and I hitched up my sagging pants, hand-me-downs from my sisters that were short and threadbare.

Secretary Sun walked along the line, his steps slow and precise, pausing before each girl: the bony ones, the short ones, the village beauty renowned for her deep dimples and petal-soft skin. At last, he stopped at me.

All of us had volunteered for the troupe to get out of field work, but we hadn’t practiced in months. Ten thousand hours of rehearsals wouldn’t have improved our performances. Only my neighbor, who accompanied us on his bamboo flute, possessed any talent. With a nod at us, Fatty Song played an old tune, one that my grandparents had hummed as children about the long days of summer, of sunshine and dreams. The words had been changed and put into the service of the people.

As we sang about victory and freedom, we acted out each verse. We raised our arms above our heads, to imitate the sun rising from the east—the east, where the dawn, where revolution began. I stretched as high as I could, a taut line from my toes to the tips of my fingers, and set my jaw, trying to look fierce. When I glimpsed the girl beside me, though, I almost laughed out loud—her face squinched up as if she was suppressing a gigantic sneeze. Then I faltered, wondering if I might look like her.

Afterward, we lined up again. Our shuffling feet had kicked up the tickling scent of chickens, dust, and straw. Taking my place at the end, I hunched over, panting, sweat dripping down my back. I was the tallest girl, broad-shouldered and gangly, awkward as a baby calf.

Secretary Sun examined each candidate for a second time. Everyone in my village shared the same surname, Song. Our neighbors knew my parents, had known my grandparents. They recognized the inherited shape of my ears, my temper, and my fate, and had me determined while I was still in the womb.

It was 1965, a time ripe with prospect, even if in my village, the buckets of night soil still turned rank and the Party’s painted slogans cracked in the heat. That year, our persimmon trees hung heavy and heady with fruit. In late autumn, we’d heap them into luminous piles, treasures rich as any robber-king’s.

Cicadas droned, their song monotonous yet haunting, punctuated by the flick of their wings. Such tiny creatures, yet together, they were deafening. To my left, my neighbor sucked on the end of her braid. To my right, another tugged on her tunic and rubbed her nose, covered by a glistening mole.

My two sisters, too old to volunteer to perform for the troupe, pushed to the front of the crowd. As the official looked over us again, I prayed to the Chairman, asking him to grant me the opportunity to serve. The people’s republic had been born the same year as me, and we were both still testing our limits, still ricocheting between extremes as we figured out who we would grow up to be.

Besides performing revolutionary songs, I could dig a ditch, spin wool, and demonstrate other skills that our leaders might want to review. I imagined the Chairman beaming, his hand outstretched, and mine reaching up to meet his. My looks didn’t matter, only my courage.

Female heroes were few but vivid in the tales we learned at school: A teenage spy beheaded after she rallied villagers against enemy soldiers. A factory worker burned to death after she stopped a huge fire. A peasant killed when she held together a collapsing kiln. I wanted the official to pick me for this duty and to separate me from the rest of the girls in the village, from everyone here. I wanted to live like a hero.

If the official didn’t select me, in a year I might get married. In time, I would have a baby, then another and another. I had to act now; it might be my only chance. Catching Headman Song’s eye, I floated my hands in a gesture only he would understand. I swiveled my head over the length of the crowd as if to say, I will tell everyone. When his mouth twitched, I knew he understood. Headmen elsewhere in Hebei province had been beaten for lesser offenses, for the people hungered to humble the powerful. To listen to their confessions, strip their authority, force them to clean latrines and catch flies in a jar. Even if only some believed the secret I held, the headman’s reputation would suffer, for such was the strength of accusation in those days.

The cicadas rose in pitch, a teeming, throbbing sound. Headman Song took the pipe from his mouth, turned to the official, and they spoke with their heads bowed.

When Secretary Sun returned and stopped in front of me, resting his hand on my shoulder, I didn’t shy away.

No one else in the village knew what I’d seen. Two years ago, a traveling musician had sought shelter here. Although he wore the same rough clothes as the rest of us, his pale skin glowed, and his high haunting voice silenced us in a performance fit for the Chairman. He sang of heroes, of a mischievous monkey king who rebelled against the heavens, while he plucked at a pipa, the melody spooling from his fingers. Every family volunteered to house the musician that night, for we’d never had such a remarkable visitor. Headman Song prevailed, and he moved his wife and four children to his brother’s home to provide quiet for his guest.

In the middle of the night, I slipped out and crept to the headman’s house in the hopes of another song. Instead I heard grunts, and through a crack in the front door, I saw their shadows on the wall come together and apart, flickering in the firelight. I moved away, but then peeked back in. The musician kneeled on all fours, the headman behind him. Their hands reached, touched, twined. As the headman let out a low moan, their rocking mesmerized me until both men had shuddered and gone still. I bumped against a stack of baskets. Though I caught them in time to keep the baskets from toppling over, the headman burst through the door, naked. His nipples, large and flat, were startling, an unblinking pair of eyes. Scowling, he gripped my wrists, and his body was heavy with a thick soapy smell. I didn’t scream, and after a long moment, he released me. He must have known I would keep his secret—until today, when I floated my hands as the traveling musician once did over the strings. Over the headman.

That night, Ba gave me the biggest portion of millet porridge, the one reserved for him. Our family sat cross-legged at the low table that rested upon the raised brick bed. When the nights chilled, we’d stoke fires in the hearth beneath the bed to keep us warm. My sisters watched, their faces pinched with hunger, with jealousy, as he plucked mushrooms drizzled with soy sauce from his own bowl and dropped them into my porridge. I inhaled the scent. Our village was famed for its soy sauce, its dark fermented flavors redeeming our bland, insubstantial meals. We fermented the sauce in giant urns, pungent proof that the simplest ingredients could be transformed with time. I pushed the mushrooms to the side of the bowl, saving them for last.

“Our Mei Xiang,” he said. Fragrant Plum Blossom.

I looked up. He almost never called me by my name. In our family—like all the families in our village—we referred to one another by our titles, by our roles: Ma and Ba, First, Second, and Third Daughters.

As the stove flickered low, Ba went outside, where he fell into a fit of coughing. He might have been trying to hide it from us; all of us pushed through our illnesses. The stinking herbal brews Ma prepared never cured us completely.