Excerpt

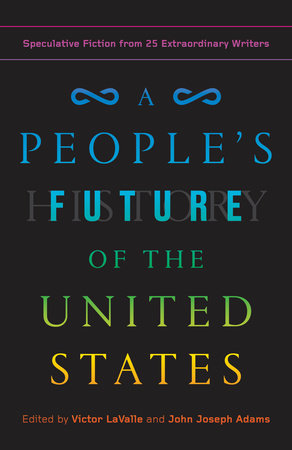

A People's Future of the United States

The Bookstore at the End of AmericaCharlie Jane Anders

A bookshop on a hill. Two front doors, two walkways lined with blank slates and grass, two identical signs welcoming customers to the First and Last Page, and a great blue building in the middle, shaped like an old-fashioned barn with a slanted tiled roof and generous rain gutters. Nobody knew how many books were inside that building, not even Molly, the owner. But if you couldn’t find it there, they probably hadn’t written it down yet.

The two walkways led to two identical front doors, with straw welcome mats, blue plank floors, and the scent of lilacs and old bindings—but then you’d see a completely different store, depending which side you entered. With two cash registers, for two separate kinds of money.

If you entered from the California side, you’d see a wall-hanging: women of all ages, shapes, and origins, holding hands and dancing. You’d notice the display of the latest books from a variety of small presses that clung to life in Colorado Springs and Santa Fe, from literature and poetry to cultural studies. The shelves closest to the door on the California side included a decent amount of women’s and queer studies but also a strong selection of classic literature, going back to Virginia Woolf and Zora Neale Hurston. Plus some brand-new paperbacks.

If you came in through the American front door, the basic layout would be pretty similar, except for the big painting of the nearby Rocky Mountains. But you might notice more books on religion and some history books with a somewhat more conservative approach. The literary books skewed a bit more toward Faulkner, Thoreau, and Hemingway, not to mention Ayn Rand, and you might find more books of essays about self-reliance and strong families, along with another selection of low-cost paperbacks: thrillers and war novels, including brand-new releases from the big printing plant in Gatlinburg. Romance novels, too.

Go through either front door and keep walking, and you’d find yourself in a maze of shelves, with a plethora of nooks and a bevy of side rooms. Here a cavern of science fiction and fantasy, there a deep alcove of theater books—and a huge annex of history and sociology, including a whole wall devoted to explaining the origins of the Great Sundering. Of course, some people did make it all the way from one front door to the other, past the overfed-snake shape of the hallways and the giant central reading room, with a plain red carpet and two beat-down couches in it. But the design of the store encouraged you to stay inside your own reality.

The exact border between America and California, which elsewhere featured watchtowers and roadblocks, you are now leaving/you are now entering signs, and terrible overpriced souvenir stands, was denoted in the First and Last Page by a tall bookcase of self-help titles about coping with divorce.

People came from hundreds of miles in either direction, via hydroelectric cars, solarcycles, mecha-horses, and tour buses, to get some book they couldn’t live without. You could get electronic books via the Share, of course, but they might be plagued with crowdsourced editing, user-targeted content, random annotations, and sometimes just plain garbage. You might be reading The Federalist Papers on your Gidget and come across a paragraph about rights vs. duties that wasn’t there before—or, for that matter, a few pages relating to hair cream, because you’d been searching on hair cream yesterday. Not to mention, the same book might read completely differently in California than in America. You could only rely on ink and paper (or, for newer books, Peip0r) for consistency, not to mention the whole sensory experience of smelling and touching volumes, turning their pages, bowing their spines.

Everybody needs books, Molly figured. No matter where they live, how they love, what they believe, whom they want to kill. We all want books. The moment you start thinking of books as some exclusive club, or the loving of books as a high distinction, then you’re a bad bookseller.

Books are the best way to discover what people thought before you were born. And an author is just someone who tried their utmost to make sense of their own mess, and maybe their failure contains a few seeds to help you with yours.

Sometimes people asked Molly why she didn’t simplify it down to one entrance. Force the people from America to talk to the Californians, and vice versa—maybe expose one side or the other to some books that might challenge their worldview just a little. And Molly always replied that she had a business to run, and if she managed to keep everyone reading, then that was enough. At the very least, Molly’s arrangement kept this the most peaceful outpost on the border, without people gathering on one side to scream at the people on the other.

Some of those screaming people were old enough to have grown up in the United States of America, but they acted as though these two lands had always been enemies.

Whichever entrance of the bookstore you went through, the first thing you’d notice was probably Phoebe. Rake-thin, coltish, rambunctious, right on the edge of becoming, she ran light enough on her bare feet to avoid ever rattling a single bookcase or dislodging a single volume. You heard Phoebe’s laughter before her footsteps. Molly’s daughter wore denim overalls and cheap linen blouses most days, or sometimes a floor-length skirt or lacy-hemmed dress, plus plastic bangles and necklaces. She hadn’t gotten her ears pierced yet.

People from both sides of the line loved Phoebe, who was a joyful shriek that you only heard from a long way away, a breath of gladness running through the flowerbeds.

Molly used to pester Phoebe about getting outdoors to breathe some fresh air—because that seemed like something moms were supposed to say, and Molly was paranoid about being a Bad Mother, since she was basically married to a bookstore, albeit one containing a large section of parenting books. But Molly was secretly glad when Phoebe disobeyed her and stayed inside, endlessly reading. Molly hoped Phoebe would always stay shy, that mother and daughter would hunker inside the First and Last Page, side-eyeing the world through thin linen curtains when they weren’t reading together.

Then Phoebe had turned fourteen, and suddenly she was out all the time, and Molly didn’t see her for hours. Around that time, Phoebe had unexpectedly grown pretty and lanky, her neck long enough to let her auburn ponytail swing as she ran around with the other kids who lived in the tangle of tree-lined streets on the America side of the line, plus a few kids who snuck across from California. Nobody seriously patrolled this part of the border, and there was one craggy rock pile, like an echo of the looming Rocky Mountains, that you could just scramble over and cross from one country to the other, if you knew the right path.

Phoebe and her gang of kids, ranging from twelve to fifteen, would go trampling the tall grass near the border on a “treasure hunt” or setting up an “ambush fort” in the rocks. Phoebe occasionally caught sight of Molly and turned to wave, before running up the dusty hillside toward Zadie and Mark, who had snuck over from California with canvas backpacks full of random games and junk. Sometimes Phoebe led an entire brigade of kids into the store, pouring cups of water or Molly’s homebrewed ginger beer for everyone, and they would all pause and say, “Hello, Ms. Carlton,” before running outside again.

Mostly, the kids were just a raucous chorus, as they chased each other with pea guns. There were times when they stayed in the most overgrown area of trees and bracken until way after sundown, until Molly was about to message the other local parents via her Gidget, and then she’d glimpse a few specks of light emerging from the claws and twisted limbs. Molly always asked Phoebe what they did in that tiny stand of vegetation, which barely qualified as “the woods,” and Phoebe always said: Nothing. They just hung out. But Molly imagined those kids under the moonlight, blotted by heavy leaves, and they could be doing anything: drinking, taking drugs, playing kiss-and-tell games.

Even if Molly had wanted to keep tabs on her daughter, she couldn’t leave the bookstore unattended. The bi-national design of the store required at least two people working at all times, one per register, and most of the people Molly hired only lasted a month or two and then had to run home because their families were worried about all the latest hints of another war on the horizon. Every day, another batch of propaganda bubbled up on Molly’s Gidget, from both sides, claiming that one country was a crushing theocracy or the other was a godless meat grinder. And meanwhile, you heard rumblings about both countries searching for the last precious dregs of water—sometimes actual rumblings, as California sent swarms of robots deep underground. Everybody was holding their breath.